Note added April, 2017: A more current and in-depth treatment of the price-elasticity of U.S. gasoline usage may be found in our Sept 2015 blog post, What an Energy-Efficiency Hero Gets Wrong about Carbon Taxes. — editor.

With gas at $3.50 a gallon in April, the U.S. mainstream media is replete with stories of drivers abandoning SUV’s, hopping on mass transit, and otherwise cutting back on gasoline. Yet a year or two ago, when pump prices were approaching and even passing the $3.00 “barrier,” the media mantra was that demand for gasoline was so inelastic that high prices were barely making a dent in usage.

Which story is correct? We lean toward the more “elastic” view, and here we’d like to share some of the data that inform our belief.

I’ve been tracking official monthly data on U.S. gasoline consumption for the past five years, and compiling the numbers in this spreadsheet. You’ll find that it parses the data in several different ways: year-on-year monthly comparisons (say, March 2008 vs. March 2007); three-month moving averages that smooth out most of the random variations in reporting; and full-year comparisons that allow a bird’s-eye view.

I’ve been tracking official monthly data on U.S. gasoline consumption for the past five years, and compiling the numbers in this spreadsheet. You’ll find that it parses the data in several different ways: year-on-year monthly comparisons (say, March 2008 vs. March 2007); three-month moving averages that smooth out most of the random variations in reporting; and full-year comparisons that allow a bird’s-eye view.

Here’s what we see in the data:

- Gasoline demand is trending downward, though only slightly. In the 49 year-on-year comparisons, monthly gasoline use dipped below the year-earlier level only eight times, but these include each of the last five months (see Moving Avgs worksheet in the cited spreadsheet).

- Gasoline’s short-run price-elasticity is rising. After a low of -0.04 in 2004, the short-run price-elasticity increased to -0.08 in 2005, -0.12 in 2006 and -0.16 in 2007. (I assume an “income-elasticity” of two-thirds in calculating price-elasticity; again, see Full Years worksheet.)

- A big reason that gasoline use kept rising until recently was the growing economy. Demand is heavily affected by economic activity. The minimum year-on-year GDP growth for any month in all four years was plus 1.7% (see Moving Avgs worksheet).

- Another reason gasoline demand was slow to drop is that the price signal, while significant, was less than advertised. Adjusted for general inflation, the average 2007 pump price was only 54% higher than the 2003 price. Amid all the talk of a doubling or even tripling in gas prices, it’s sobering to learn that you have to go all the way back to 1998 to find the last year that the real price was just half the 2007 price.

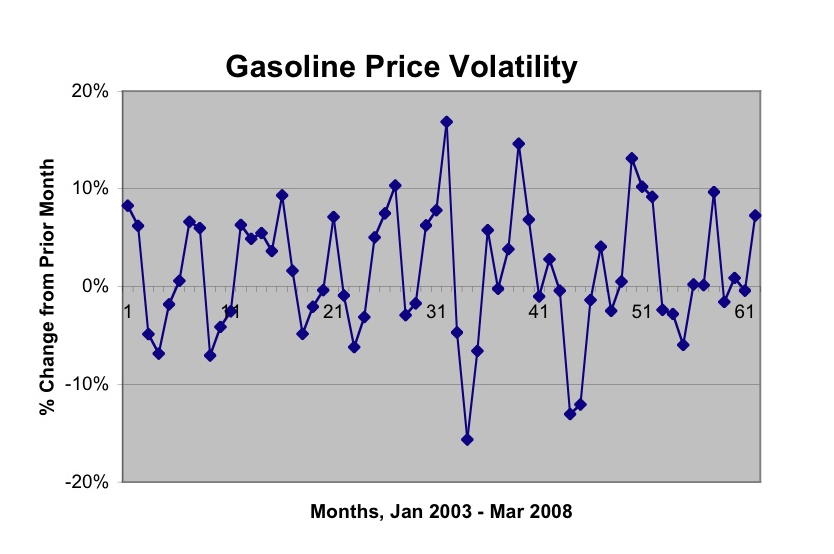

- The biggest market barrier of all may have been gasoline price volatility. The spreadsheet spans 63 months, allowing 62 month-to-month comparisons. In 29 of these, the price went down (see 1-yr comparison worksheet). That’s right: the average gasoline price was less than the prior month’s an astounding 47 percent of the time (see graph). Pump prices have been so volatile that consumers didn’t know whether the price three months later would be up or down. The result? American families and automakers alike found it hard to justify long-term investments in more-efficient cars. And allied policies like de-subsidizing sprawl didn’t get taken seriously.

- Nevertheless, gas prices have now risen five years in a row and are virtually certain this year to chalk up a sixth. There hasn’t been a comparable period of sustained increases since the late 1970s.

The big takeaway for carbon taxes is that the short-run price-elasticity of gasoline demand is rising (Point #2). (The long-run price-elasticity is probably around minus 0.4, as we discuss here.) While a rising elasticity contradicts the standard economic model in which price-sensitivities don’t change much over time, Point #5 provides a reasonable explanation: gasoline prices (and energy prices in general) had fluctuated so wildly for decades, and a sense of entitlement to cheap gasoline had become so ingrained in American society, that it took a long time for households and businesses to internalize the rise in pump prices — to regard it as real.

Perhaps now, however, a line has been crossed. Maybe the trigger was the price of crude breaching $100 a barrel, or the unspooling credit crisis signaling a fundamental change in the U.S. economy. Or it may simply have been the accumulating weight of price increases noted in Point #6. Whatever the reason(s), Americans seem, finally, to be getting the message that higher gas prices are here to stay.

That’s good news for the climate, national security, and green jobs. But bitter medicine for hard-pressed families as well as business and jobs that aren’t oil-intensive but are being pulled under by gasoline-caused belt-tightening. Imagine if the price rises had been delivered not by a rapacious market but via socially determined ramped-up increases in the gasoline tax (as some commentators have proposed since the 1970s, including, with renewed urgency, after 9/11).

Americans would have had time to adapt, along with real choices such as truly fuel-efficient cars and smaller houses in more-compact developments. And the extra revenues from the higher-priced gasoline would have belonged to all of us rather than just the owners of oil reserves. Those revenues could have been returned to households and businesses via tax-shifts or dividends, and not skimmed off for private enrichment.

The analogy to a revenue-neutral carbon tax couldn’t be more clear.

Richard A. says

Paul Krugman writes in his 5/9/08 blog,"In the long run, the best estimate of the price elasticity of demand for auto fuel seems to be -0.7. That is, a 10 percent rise in prices will reduce gas consumption by 7 percent. Of this, 4 points come from shifting to cars with better mileage, 3 points from driving less." http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/05/09/prices-and-gasoline-demand/

James Handley says

It’s a Seller’s Market Now. Price Volatility just increases the pain.

Recent reports suggest that we’re crossing from a buyer’s market (in which profits were maintained by limiting supply, via monpolies like Standard Oil or cartels like OPEC) to a seller’s market, in which demand always exceeds the available supply of petroleum. Reasons include China and India’s embrace of car culture (promoted by US policy), limited refining capacity, as well as declining productivity of many oil fields.

In the transition range, prices are likely to be extremely volatile — sometimes strongly affected by supply, sometimes more by demand, but always moving and often sharply.

Once we’re firmly into the "seller’s market," fuel price will be mostly determined by consumers’ willingness to forgo fuel by skipping car or plane trips or by carpooling or finding other ways to get around. In the longer run, people will adjust by choosing to live closer, travel differently and less and buying more efficient homes and vehicles, all of which are ways to dampen carbon emissions and thus climate impacts.

But it’s hard to imagine that these measures will be enough to reduce demand significantly below declining production rates– meaning that we’re a seller’s market for good or at least until there’s a big technological breakthrough or a major shift in consumption patterns.

Volatility makes deciding how much to invest in making efficiency improvements more of a gamble than a smooth, upward price arc would. That’s a very big flaw of the current (lack of) energy policy (as Charlie’s graph shows) and of cap-and-trade systems. They’re volatile, and unlike a predictably-increasing carbon tax, induce more "stickiness," substantially increasing the pain and duration of a transition to a low-carbon and low-petroleum economy.

Dentists reassure patients by letting them know what to expect by making it quick. At this point, our energy and climate policy consists mostly of avoiding "the dentist" and prolonging the pain. Maybe time to stop agonizing, face reality, work out something predictable, and try to avoid unnecessary shocks to our economy, our political system and international relations. A predictable gradually-increasing carbon tax that helps keep demand in balance with supply and pushes us towards a low-carbon economy, might seem scary, like a shot of novacaine, but it sure beats the alternative.

george says

Here’s one thing I know for sure about my gasoline usage. I have no choice but to use gas. Where I live, there is no public transportation that I can use to get to my place of employment. There are no trains, no buses, no cabs (unless I call for one and they aren’t cheap) I commute over 50 miles round trip a day just to get to work. Slapping a carbon tax on me and everyone else will do nothing but make it harder on all of us financially. Instead of taxing the pajesus out of all of us, new technologies should be developed that are clean and cheap that we can all use. If we keep getting taxed for every little thing, I can guarantee there will be a revolution. History has proven this time and time again.

David Collins says

George, the majority of realistic carbon tax proposals involve returning tax funds collected, on a per-person basis, reducing other taxes, or something along similar lines. This would enable you to continue to get to and from work in the meanwhile, as you and others in your situation figure out your long-term approach to handling your long commute. Personally, I trust you and your friends and neighbors to do a far better job of it than any government bureaucrats or academic dreamers ever could.

James Handley says

Well said, David!

Politicians avoid carbon taxes fearing reactions like George’s. Instead, they’re talking about cap-and-trade which would be a tax on fossil fuels.

The Lieberman-Warner cap-and-trade bill (up for a vote in the Senate soon) would transfer tax revenue to such winners as "clean coal" (Takes ~ 25% of net energy to capture and sequester carbon from coal. Wind’s more economical) biofuels like corn-based ethanol (doesn’t replace the fossil fuel it takes to make it) and nuclear (already very subsidized).

The Canadians are having a lively discussion about caps vs taxes. Some of their politicians are also advocating a cap, pretending it’s not a tax and accusing carbon tax proponents of stealing from the poor. In truth, we have choices about what to do with the tax revenue under either a cap or tax, some very good (like a dividend) and some very bad (like subsidies to the already-subsidized). Cap and Dividend would be a way to return the revenue from a cap, but it’s not the best, because a cap still creates volatility and traders skimming.

A revenue-neutral carbon tax would put the revenue back into the economy and let people like George decide how to make the needed adjustments and technological innovations instead of government contractors who have every reason to fudge their numbers to win more grants.

Andrew Israel says

Here are some other questions to consider:

1. Why should certain persons get the benefit of

commuting large distances in inefficient vehicles

if said persons have chosen to live far away from

their job. It seems to me, we all want our freedom to

choose where we want to live, drive what we want to drive,

and do so without the prospect of consumption based tax.

To me this defies logic and it chargrins me. If I work in New York Cityand I choose to live in the suburbs of New Jersey, or Connecticut what right do I have to be free of

a gasoline tax. I agree we should invest in fuel efficient

low carbon technology, but we have been saying this since

I was a kid in grade school (1976).

We all have a choices in life. Some are more costly to

our wallets and to the environment than others.

Suburbanites are enjoying a free ride and the expense

of those who live in center cities and have to be exposed

to particulate generated by cards and the like.

If I choose to live in a way that limits my carbon footprint, I think a tax should be placed on those

who feel they are entitled to drive in gas guzzling

behomoths and live in a McMansion 25 miles from their place of work. Americans think it is their birthright to

to have low taxes and access to highways. I think

this paradigm has been proven to be detrimental to

our econmic and physical health.