This page originally appeared as a category of “Supporters,” alongside other compendiums of carbon-tax supporters such as Public Officials, Thought Leaders, and Scientists & Economists. In 2019 we moved it to “Politics,” signaling the reality that the U.S. conservative movement today is almost completely devoid of supporters of meaningful climate action, much less robust carbon taxing.

Outspoken climate blogger David Roberts skewered the April 2024 Benji Becker essay noted in the text. Sadly, his critique is spot-on.

Confirmation of this sad fact appears almost daily in newspapers and other media. A particularly poignant instance was an April 2024 NY Times guest essay by one Benji Backer, founder and executive chair of the American Conservation Coalition.

The essay, grandiosely titled I’m a Young Conservative, and I Want My Party to Lead the Fight Against Climate Change, neither acknowledged conservatives’ sabotaging of climate action throughout the current century nor offered a single original or innovative policy solution — not even a revenue-neutral carbon pricing program such as fee-and-dividend, which is sometimes optimistically termed a carbon tax that “conservatives could love” for offering Pigovian taxation in a non-government-expanding form.

Somewhat similarly, a January 21, 2024 Washington Post story, N.H.’s primary pushed the GOP to fix acid rain. Climate change is another story., contrasted 1988 Republican presidential candidates vowing aggressive action against acid rain emissions from Midwestern power plants, with 2024 G.O.P. candidates disparaging or outright ignoring questions about combating climate change:

George H.W. Bush promised to restore his party’s conservation ethic and curtail pollution. His top competitor, Senate Republican leader Bob Dole, vowed to quickly pass an acid rain bill. The state’s voters and its Republican governor, Gov. John H. Sununu, had elevated the issue before the primary vote that helped propel Bush to the White House, where he followed through by signing legislation that has curtailed acidity in New Hampshire by 84 percent to date.

Now, however, as New Hampshire faces the much broader threat of climate change, Republican candidates in the state for Tuesday’s primary are barely mentioning the issue — and when they do, it is often to play it down.

Haley advocated pulling out of an international climate deal as President Donald Trump’s ambassador to the United Nations; she has said “man-made climate change is real, but liberal ideas would cost trillions and destroy our economy.” Trump calls climate change a “hoax.” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has said he supports efforts to address the impact of hurricanes and flooding, but he rejects “the politicization of the weather.”

Republican Gov. Chris Sununu, the son of the former governor, said in an interview that he sees no comparison between dealing with acid rain and climate change.

Climate change is a completely different story,” the younger Sununu said. “There’s a lot of politics behind that kind of socialistic approach, that green New Deal type stuff that costs trillions of dollars.”

Nevertheless, from time to time Republican and other conservative-identifying office-holders express support for some form of carbon pricing. Such expressions tend to be tentative and vague.

Opening 9 paragraphs, verbatim, from “Delay as the New Denial: The Latest Republican Tactic to Block Climate Action,” by Lisa Friedman & Jonathan Weisman, July 22, 2022. Emphasis added, link in text.

Tellingly, not one of the 50 Republican U.S. Senators supported even a single element of President Biden’s 2021-2022 Build Back Better climate-investment program, either at the outset or in any of its increasingly stripped-down versions. In July 2022, NY Times climate reporter Lisa Friedman and congressional correspondent Jonathan Weisman distilled this monolithic resistance in a front-page story, Delay as the New Denial: The Latest Republican Tactic to Block Climate Action, which we’ve excerpted in the text-box at right.

It paints a dismal picture, with Senators Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Mike Crapo (R-ID) uttering counterfactual and nonsensical word salads, respectively.

Notably, and unfortunately, the Times story granted Capitol Hill Republicans a convenient out: saying “that they believe that … market forces would somehow develop solutions to the carbon dioxide that has been building in the atmosphere, trapping heat like a blanket around a sweltering Earth,” without challenging them to say how stiff a carbon tax they would support or why they won’t support one at all.

Expressions of support for carbon pricing by Republican / Conservative office-holders

Nineteen Republican members of the Utah legislature declared support for the carbon-fee-and-dividend approach to carbon taxing in a June 4, 2021 op-ed in Salt Lake City’s Deseret News, Republicans Need to Engage in Climate Politics. The op-ed is a classic expression of free-market ideology on climate and carbon pricing, most notably in this passage:

Emissions can be cut either with regulations, incentives or price signals. Regulations are heavy-handed and growth-inhibiting. They burden the economy, they cost American jobs, and they end up exporting our emissions to other countries. Incentives can work, but they let government choose the winners and losers, and too often end up becoming permanent entitlements. We believe the best way to cut emissions is with a price signal to the private sector, which lets competition and innovation find the solutions.

We support a carbon dividends approach that puts a fee on carbon emissions and returns all the money to the American people in dividend checks. This approach does not require heavy-handed government oversight. The fee gives the markets an incentive to move to cleaner technologies, while the dividend protects families from the effect of higher energy prices. Most families should come out financially ahead, and they will be rewarded for reducing emissions however they choose. All will benefit from the cleaner air that will result from these policies. (emphases added)

It should be said that those “heavy-handed, growth-inhibiting” regulations also improve air quality, even if less efficiently than carbon pricing. Moreover, even perfect pricing (full cost-internalization of climate and air pollution damage) won’t by itself overcome deep-seated market barriers such as split incentives and deficient infrastructure that holds back climate solutions such as electric vehicles (inadequate charging) and bicycling (danger from motorists). Carbon pricing on its own won’t eliminate climate pollution. Also missing from the op-ed was the size of the proposed carbon fee; clearly, a $20/ton carbon fee and a $15/ton fee that ramps up by $10/ton each year would be vastly different in impact.

Nevertheless, the statement wasn’t aimed at Salt Lake City — the signatories aren’t seeking a state carbon fee. Rather, it was aimed at Utah’s Republican senators, notably Sen. Mitt Romney, who from time to time has signaled openness to some form of carbon price. It’s a good start.

Former Congressmember Bob Inglis (R-South Carolina): A 2023 update

Bob Inglis, a mild-mannered, plain-spoken but steely South Carolina Republican who served six terms in Congress in the late nineties and aughts, has earned his own section on this page (see further below) for his long-time advocacy of a U.S. carbon tax.

A new (January 2023) piece by Inglis in The Hill, Dancing around the obvious climate solution, merits pride of place here for its unambiguous call for a U.S. carbon tax, notwithstanding that its basic pitch — a federal carbon tax of unspecified magnitude, with the revenues recycled through reductions in federal payroll taxes on wages — is completely unchanged from 2008.

“[W]hat if we paired a carbon tax with a cut in payroll (F.I.C.A.) taxes, exercising the right of self-governing people to change what we tax?,” Inglis asks. “Such a tax swap requires trust, and that trust will come only if Republicans and Democrats work together.”

Inglis’s Hill post specifies two opportunities for the two parties to build trust. One is to negotiate and enact permitting reform to expedite construction of transmission lines and other clean-energy accoutrements from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. The other is to enact a U.S. version of the pending European Union carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) that could incentivize other countries to enact carbon taxes to forestall other countries from taxing their exported products for above-average embodied carbon content.

Inglis’s faith in both free enterprise and the party whose primary he lost in the 2010 Tea Party season is boundless, as his Hill peroration shows:

Our ability to govern ourselves is at the heart of who we are as Americans. We can decide to untax some form of income, to put a tax on carbon dioxide instead and to apply that tax to imports. That would get the world “in” on solving climate change, and accountable free enterprise would deliver innovation at scale and fast.

Unfortunately, the post-Tea Party version of the Republican Party now in control of the House of Representatives is, by nearly all accounts, more interested in beating up on Democrats than in working with them, and more concerned with holding power than deploying it for the common good. We wish Inglis — a lovely man, from our meetings with him — well.

Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah)

Utah’s junior United States senator, Mitt Romney, was formerly governor of Massachusetts (2003-2007) and Republican candidate for president (2012), as well as a successful businessman. His generally moderate record as governor of Massachusetts, along with some striking departures from right-wing Republican orthodoxy, as in voting to convict President Donald Trump in both impeachment trails (2020 and 2021) and marching in a Black Lives Matter protest (2020), have led some observers to believe that Sen. Romney might someday support carbon-pricing legislation in Congress.

In America Is in Denial, an article published in The Atlantic in July 2022 — on Independence Day, in fact — Romney decried what he called “our national malady of denial, deceit, and distrust.” He also lamented President Biden’s inability to “break through” that malady. “Too many Americans,” he wrote, “are blithely dismissing threats that could prove cataclysmic.” In Romney’s telling, those dismissed threats included climate change.

Senators Mitt Romney & Joe Manchin, March 30, 2022, Washington Post photo by Jabin Botsford.

Of course, one way that Sen. Romney could have helped Pres. Biden break through that national malady of distrust was by offering his tie-breaking vote in favor of the administration’s ambitious, climate-oriented Build Back Better legislative package. Then again, Build Back Better, a classic “big government”-style program that Republicans habitually abjure, save for military, policing and fossil fuel-related measures, wasn’t the kind of measure a traditional Republican like Romney would readily support. Carbon pricing, however, is policy of a different stripe. Not only is it said to be “market-based” (here at CTC, we prefer to call carbon pricing a market corrective), it can also be rendered as a revenue-neutral policy that won’t expand government, either as a tax swap or via a carbon-dividend approach.

And from time to time, Romney has evinced interest in carbon pricing. In October 2021, Utah’s flagship paper, Deseret News, quoted him telling the libertarian-oriented Milken Institute that “There is only one change that dramatically affects the amount of global emissions and that is a price on carbon.” Romney went on to say that “They (Democrats) talk about like this is the holy grail. And they know it is the only thing that really makes a difference. But they are not planning on doing it in reconciliation and I do not understand why.” The same Deseret News article also had Romney telling the paper that, while he “said he is not a fan of the reconciliation measure, [he] said it at least ought to include a tax on carbon.”

Fine rhetoric, but readers should note two things before they get carried away. First, in his remarks Romney appeared to be primarily touting “border carbon adjustments” that would tax imports of commodities manufactured with high emissions, rather than economy-wide U.S. carbon pricing. Second, Romney never apparently tried to corral fellow Republican senators to join his putative pro-pricing position. He has never introduced carbon-pricing legislation, nor has he co-sponsored any of the raft of carbon pricing bills introduced by Democratic counterparts such as Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse.

While we don’t know the point of Romney’s game, it doesn’t seem wise to construe occasional professions of interest in carbon pricing as genuine support.

American Enterprise Institute staffer touts idea of carbon tax (January 2022)

The American Enterprise Institute is the corporate right’s avatar of the established economic order — a reliable, conventional source of policy analysis in support of expanding economic production, limiting taxation, and deregulating U.S. health, safety and environmental practices.

In the heady days of 2006-2008, AEI published a steady stream of papers backing carbon taxes as a way of reducing carbon emissions without the presumed heavy hand of government regulations, standards and subsidies. (Several of these are referenced at the end of this long entry.) Beginning in 2010, however, with the ascension of the Tea Party and the abandonment of the climate cause by the vast majority of Republican elected officials, AEI became less voluble in supporting meaningful climate policy including carbon pricing.

To be sure, some AEI staffers did post pieces expressing positive words about carbon taxing, as a CTC friend reminded us with this set of links: 2013, 2014, 2017, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021 and 2021. But these were largely academic and apolitical, a pattern maintained in early January (2022) with Addressing climate change and reforming the tax code with a carbon tax, by AEI senior fellow Kyle Pomerleau. The post covers the usual bases: economists love carbon taxing’s efficiency; the tax’s “natural” regressive bent makes it a tough sell to the left; more than two dozen countries have some sort of carbon tax; like all taxation, a carbon tax would cut into economic output; but there are various workarounds, so who knows, a carbon tax might some day come into being.

Yet the piece is bloodless, context-less and, in our view, not worth much attention. It’s stunningly conventional and strikingly lacking in urgency. It does not mention the exploding economic (and human) costs of climate change here and abroad, the rising geopolitical stakes, the vast health co-benefits of reducing and retiring fossil fuels. Politics are not discussed, including the unanimous refusal of the Republican Senate conference to back any of President Biden’s climate agenda.

What’s the purpose of Pomerleau’s post? If we had to guess, we’d say that AEI, mindful of the American public’s demand for climate action (fully one-third of Americans declared themselves “alarmed” over climate, in the most recent Yale – George Mason U. poll, last September), figured that an anodyne post about the hypothetical merits of carbon taxing was a good way to position themselves to the left of 2022 G.O.P. neanderthalism. We’ll happily revise our opinion, the minute the Institute comes out swinging for a specific bill embodying a non-trivial carbon tax.

NY Times: A growing number of Republicans are working to address climate change (June 2021)

The above-titled article, by Times national climate reporter Lisa Friedman, reads almost as a parody, especially its headline, variants of which have been appearing like clockwork in American newspapers for a decade or more. Its peg: a “clandestine” meeting organized by Rep. John Curtis (R-UT) at which “24 Republicans gathered in a ballroom of the Grand America Hotel in Salt Lake City where they brainstormed ways to get their party to engage on a planetary problem it has ignored for decades.”

The story’s barely newsworthy element was Rep. Curtis’s announcement of a “Conservative Climate Caucus” aimed at educating other Republicans about climate change and “developing policies to counter ‘radical progressive climate proposals.’” Thirty-eight Republican House members have reportedly joined.

The proposed solutions, which Friedman reported in a companion story, Some Republicans call for a coherent climate strategy, were the usual Republican mishmash: tree planting, promotion of nuclear power, investment in nascent technologies to capture CO2 emissions from power plants,” which individually and in combination will do little to actually draw down greenhouse gases from the atmosphere,” she noted. Friedman also pointed out that neither the new caucus nor the Republicans assembled in Salt Lake City offered any specific targets for cutting emissions.

NY Times: G.O.P. Shifts on Climate, but Not on Fossil Fuels (August 2021)

Judging from the headline, this story, from Aug. 13, 2021, may have been an attempt by the Times to fix the one above from June, by clarifying that the dawning public acknowledgment of the reality of climate change by some Senate, House and statehouse Republicans isn’t accompanied by support of meaningful policies to forestall or mitigate it. Here are the lede grafs:

After a decade of disputing the existence of climate change, many leading Republicans are shifting their posture amid deadly heat waves, devastating drought and ferocious wildfires that have bludgeoned their districts and unnerved their constituents back home.

Members of Congress who long insisted that the climate is changing due to natural cycles have notably adjusted that view, with many now acknowledging the solid science that emissions from burning oil, gas and coal have raised Earth’s temperature.

But their growing acceptance of the reality of climate change has not translated into support for the one strategy that scientists said in a major United Nations report this week is imperative to avert an even more harrowing future: stop burning fossil fuels.

Instead, Republicans want to spend billions to prepare communities to cope with extreme weather, but are trying to block efforts by Democrats to cut the emissions that are fueling the disasters in the first place.

[Emphasis added. Note that the headline above is taken from the print edition; the digital headline is the more anodyne “Amid Extreme Weather, a Shift Among Republicans on Climate Change.”]

Still, the August story noted helpfully, and accurately, that while “A few Republicans, like Senator Mitt Romney of Utah and Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, have said they support charging companies for the carbon dioxide they generate, a strategy that economists say would create a powerful incentive to lower emissions … neither man is championing such a measure with any urgency.” In other words, counting on Republicans to climb aboard the carbon tax or price train in 2021 is a fool’s errand.

David Roberts: “Climate change is intrinsically insulting to conservative values.” (April 2019)

A catalyst for this change was David Roberts’ April 2019 post, Don’t bother waiting for conservatives to come around on climate change. (Emily Atkins posted a briefer but similarly pitched piece on May 8 at The New Republic, The Republicans Are Dead to Planet Earth.) Roberts grouped right-wing / Republican expressions of climate policy interest into three approaches: associations, libertarian and innovation. Each was found wanting:

The “associations approach” attempts to identify existing conservative identities, subgroups like veterans or Catholics, that might be persuadable on climate. None of these efforts have succeeded on any appreciable scale.

The “libertarian approach” pitches climate solutions amenable to fiscal conservatives, like carbon “tax and dividend” systems that don’t grow the size of government. Despite the boundless faith many have invested in this approach, it hasn’t yielded much either.

The “innovation” approach seeks to narrow in on climate policies that overlap with existing conservative interests, which amount, as I wrote in this post, to subsidies for fossil fuel companies, for their research on how we can keep burning fossil fuels. Oh, and nuclear.

In his post Roberts also drew on a range of research, including demographic analysis of America’s “big sorting” into urban vs. rural, and Jonathan Haidt’s “moral foundations” theory, to argue that “climate change is intrinsically insulting to conservative values.” His diagnosis: “The populace needs to be made less conservative.”

FiveThirtyEight: “Why The Republican Party Isn’t Rebranding” (April 2021)

In an April 2021 post, Why The Republican Party Isn’t Rebranding After 2020, FiveThirtyEight political analyst Perry Bacon Jr. listed five dynamics that he believes are keeping the G.O.P. from altering course, despite losing the House, Senate and White House in 2020 and being implicated in the violent Jan. 6 insurrection:

- The party’s core activists don’t want to shift gears.

- Trump is still a force in the party.

- Republicans almost won in 2020.

- Republican voters aren’t clamoring for changes.

- There aren’t real forces within the GOP leading change.

Bacon writes that “The collective decision of conservative activists and Republican elected officials to stay on the anti-democratic, racist trajectory that the GOP had been on before Trump — but that he accelerated — is perhaps the most important story in American politics right now.”

His essay is an attempt to understand why. We recommend it highly for anyone looking for a break from Republicans’ virtually monolithic anti-climate stance, anytime soon.

The Last House Republican to Back a Carbon Fee

In Nov 2018, House Republican Francis Rooney (FL-19) joined six Democratic Congressmembers including Rep. Ted Deutch, co-founder of the Climate Solutions Caucus, in co-sponsoring the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act. EICDA would impose an initial “upstream” charge of $15 per ton of CO2 from combustion of fossil fuels, with the charge increasing annually by $10 per ton. All of the revenues would be placed in a trust fund whose proceeds would be returned as “dividends” to U.S. households.

The EICDA embodied the fee-and-dividend approach espoused by Citizens’ Climate Lobby and long supported by the Carbon Tax Center, climate scientist-advocate James Hansen and others. The carbon charge embodied in the EICDA is aggressive, taking just nine years to surpass $100/ton (though it could be said that onrushing climate events such as ice caps melting and Australian and western U.S. wildfires, warrant a steeper trajectory). In this sense, the bill’s co-sponsorship by Rep. Rooney, a Republican, was a major positive step.

But not a breakthrough. Rep. Rooney never actively fought for his bill. EICDA was barely visible on his Web site; it appeared perfunctorily on a hard-to-find page for co-sponsored bills, in contrast to Rep. Deutch’s site, which included both a press release for the bill and a YouTube video forcefully outlining its rationale for his constituents and the nation as a whole. Based on a Google search and his Web site, Rep. Rooney generally refrained from touting the bill and instead limited his climate advocacy to broad generalities.

Rooney’s reticence about championing his fee-and-dividend bill was in stark contrast to GOP Rep. Justin Amash’s willingness to buck Republican orthodoxy in calling for impeachment of President Trump. In any event, as of Jan. 2021 Rooney is no longer in the House. He retired from politics in 2020.

George P. Shultz

Stalwart Republican and conservative elder statesman George P. Shultz championed revenue-neutral carbon-taxing in the decade leading up to his death on Feb. 7, 2021 at age 100. In op-eds, in public presentations, and in his service on the advisory boards of Citizens Climate Lobby (CCL) and the Niskanen Center, Shultz advocated for U.S. adoption of the “fee-and-dividend” form of carbon taxing that distributes all carbon tax revenues equally (“pro rata”) to U.S. households. The idea is to instill the price incentive of a carbon tax throughout the economy without increasing the size and reach of government.

Shultz’s conservative pedigree and illustrious bio — he served Republican presidents Nixon and Bush (41) in four Cabinet-level positions: budget director, labor, treasury and state — lent gravitas to his support for carbon taxing, as the Niskanen Institute’s Joseph Majkut intimated in his affectionate Feb. 10 (2021) tribute, Shultz, Conservatism and Carbon Pricing:

On February 7, we lost one of our most revered and beloved statesmen, George Shultz. His absence is a loss for both the country and the world, and his legacy of service and diligence will be remembered. Shultz’s lifetime of service was an example of patriotic and conservative leadership, not least in his support for immediate and forceful action against climate change.

Shultz was no progressive green. He was a life-long Republican and a conservative. After military service and graduate studies, he joined the faculty at the University of Chicago, and was influenced by renowned free-market economists Milton Friedman and George Stigler. Steeped in free-market thinking, he served in the Nixon Administration, returned to the private sector, and then served in the Reagan Administration as Secretary of State, helping the President forge a relationship with the Soviet Union and free half a continent from communist rule. Decades later, he would embrace a carbon tax as a prudent, even a conservative, response to climate change. (emphases added)

For a sampling of Shultz’s opinions on carbon taxing, see Stanford’s George Shultz on energy: It’s personal, published in the Stanford Report, July 2012. Following is an excerpt from Shultz’s op-ed, How to Gain a Climate Consensus, in the Washington Post, Sept. 5, 2007:

The use of economic incentives (caps and trading rights, and carbon taxes) is essential to avoid disastrously high costs of control. The cap-and-trade system has been highly successful in reducing sulfur dioxide emissions by electricity utilities in the United States. That system relies on a scientifically valid and accepted emission-measurement system used by a clearly identified and homogeneous set of utilities. Fortunately, such a careful system of measurement exists for a viable greenhouse gas regimen. The product of collaboration between the World Resources Institute and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, these standards for accounting and reporting greenhouse gases should be duly understood and adopted. Even with clear units of account, however, large problems arise as the coverage and heterogeneity of the system grow. And for trading across borders, the system needs to be accepted among the trading partners. Scams are easy to imagine. No nation should be allowed to trade without a verifiable, transparent system of measuring and monitoring of reductions, and holding emitters accountable. In many respects, a straight-out carbon tax is simpler and likelier to produce the desired result. If the tax were offset by cuts elsewhere to make it revenue-neutral, acceptability would be enhanced.

Unfortunately, Shultz left few disciples. His death leaves his fellow fee-and-dividend proponent (and fellow former Republican Secretary of State) James Baker, who serves on the board of the Climate Leadership Council, as the lone prominent Republican voice for climate action via carbon taxing.

To our knowledge, none of the 20-odd sitting Republicans currently listed as members of the Climate Solutions Caucus has made a single public utterance in support of carbon taxing since at least the 2018 midterm elections. Only two Republican caucus members voted in Jan. 2021 to impeach then-President Trump for inciting the Jan. 6 Capitol invasion: Rep. Fred Upton (R-MI-06) and Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-IL-16). Indeed, among the caucus members are some House Republicans who voted against certifying Joe Biden’s electoral college win on Jan. 6, including Rep. Lee Zeldin (R-NY-01), Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-NY-21), and the especially unhinged Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL-01).

Conservatives’ fragility on climate action

There may be no more compelling climate apostate than Jerry Taylor, an adamant climate denier during his two decades’ tenure at the Cato Institute but, since 2014, a vigorous proponent of climate action at the Niskanen Center, the think tank he founded that year.

What Changed My Mind About Climate Change?, Taylor’s May 2019 post at a new center-right opinion site, The Bulwark, tellingly recounts his conversion from denier to advocate. What is perhaps most striking about it, however, is this passage from Taylor’s email blast announcing the post:

[M]y experience is that the risk management argument resonates more powerfully with conservative audiences than does grabbing them by the lapels and screaming about the science (as warranted as that may be). Accordingly, please forgive me as I suggested more agnosticism [in my Bulwark post] than I truly feel about the strength of the scientific case for action. We need to give conservatives an out to embrace climate action without also forcing them to publicly confess that Al Gore was right all along (even though he was). (emphasis added)

The sad truth is that Taylor is probably right.

- * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(The remainder of this page, written and posted between 2014 and early 2017, is retained for historical value.)

Some conservatives have been willing to discuss and even endorse carbon taxes as the cornerstone of climate policy that fits within their principles of free markets and individual choice, though in many instances this support comes heavily hedged. At this writing (May 2017), there are three prominent loci of support for — or, at least, openness to — carbon taxing among U.S. conservatives:

- A March 2017 resolution “expressing the commitment of the House of Representatives to conservative environmental stewardship,” signed by 20 House Republicans.

- The Climate Leadership Council, which in Feb. 2017 issued “The Conservative Case for Carbon Dividends,” a policy brief signed by Republican senior statesmen George Shultz and James Baker, among others.

- The Niskanen Center, a libertarian think-tank headed by one-time climate denier Jerry Taylor that has become a beehive of thoughtful, analytical carbon tax advocacy rooted in free-market ideology.

This page summarizes recent activity by these groups, which flies in the face of the climate science denialism that has become a hallmark of the Republican Party, prior to and during the Trump Administration.. It also compiles statements from conservative commentators and other right-leaning public personages supporting carbon taxing — often but not exclusively as a potential revenue source to reduce the U.S. budget deficit or to finance reductions in other taxes such as the Corporate Income Tax.

Before we dive in, we have three survey articles to recommend.

One is Ben Adler’s 2015 post in Grist dissecting three contrasting streams of thought on climate policy among so-called conservative policy intellectuals. Adler’s thumbnails of positions on climate policy and economics voiced by prominent conservatives including Ross Douthat, Charles Krauthammer, Reihan Salam, Greg Mankiw and 11 others make for a fascinating and informative read.

Another is Ted Halstead’s Nov. 2015 Atlantic article, The Republican Solution for Climate Change. Subtitled “Republicans have the ability to offer a market-based solution to climate change, so why aren’t they doing it?,” the article is more an exploration of why the GOP should support carbon taxing than an explanation of why they don’t. Halstead founded the Climate Leadership Council a year later.

The third is a penetrating March 2017 story in Yale Environment 360 (published at the college’s School of Forestry & Environmental Studies), Climate Converts: The Conservatives Who Are Switching Sides on Warming.

1. 2017 House G.O.P. Climate Resolution

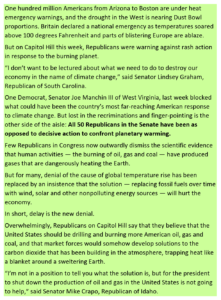

In March 2017, 17 House Republican members re-issued a 2015 resolution “expressing the commitment of the House of Representatives to conservative environmental stewardship.” (Three more signed on in May.) In a blog post in March, we called the resolution “a positive if halting step in the possible emergence of a critical mass of Republican officeholders to endorse and eventually vote for a carbon tax to combat climate change.”

Map shows the 17 GOP House members who signed the March 2017 resolution discussed in text. Their ranks grew to 20 in May.

The resolution doesn’t call for a carbon tax or any specific climate action; it doesn’t even mention “climate change,” though it does refer to “a changing climate.” In fact, the resolution is word-for-word identical to one issued eighteen months ago, in September 2015, also by 17 House Republicans, a group that included 10 of the signatories of the new resolution. (The other seven signers from 2015 are out of office — five declined to run, and two lost their seats to Democrats last November; none were “primaried” out. Of the ten new signers — counting the three who signed the resolution in May 2017 — four were newly elected to the House in 2016.)

Nevertheless, the resolution stands as a positive if halting step in the possible emergence of a critical mass of Republican officeholders to endorse and eventually vote for a carbon tax to combat climate change.

The resolution was by and for Republicans only, a not unreasonable way to strike a small flame that would not be overshadowed by solid Democratic support for climate action. The 20 Republican House signers hail almost evenly from Trump states (nine signatories) and Clinton states (eleven), with six from New York, three each from Pennsylvania and Florida, and the other eight from eight other states. Only one represents a heartland state — Don Bacon, who just won election to the House from Nebraska — though three others are from the mountain West: Mark Amodei of Nevada, Mia Love of Utah and Mike Coffman of Colorado. (See map.)

2. Climate Leadership Council

Editorial endorsements of the CLC’s carbon tax proposal span a broad ideological range.

Far and away the greatest attention-getting development in carbon taxes this year (2017) was the emergence of the Climate Leadership Council and its Feb. 2017 brief, The Conservative Case for Carbon Dividends. The paper was issued under the signatures of Republican icons James Baker and George Shultz, both of whom had served Republican presidents as secretaries of state and treasury and who personify an erstwhile (pre-Bush 43 as well as pre-Trump) Republican establishment.

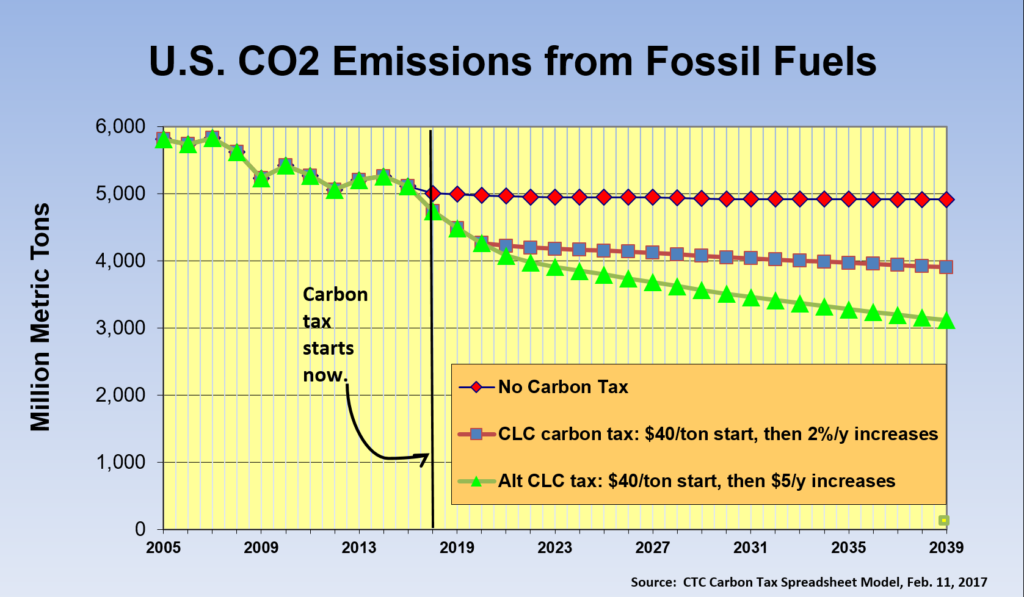

The carbon tax outlined in the council’s brief begins with a $40/ton CO2 fee, which would rise over time at an as-yet unspecified rate. One hundred percent of the carbon revenues would be returned to households as dividends, making the proposal the first Republican-branded carbon tax employing the dividend approach championed by the Citizens Climate Lobby, rather than dedicating the revenues to cutting corporate income taxes.

CO2 reductions from CLC proposal will turn on escalation rate from initial $40/ton.

CTC endorsed the proposal on the date it was issued, including the council’s proposed swap” rescinding the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan in favor of the carbon tax. “The important work of the Clean Power Plan was largely completed anyway,” we said, pointing out that roughly 80 percent of the plan’s targeted reduction in electricity-sector emissions for 2030 had already been achieved by the end of 2016. “The proposed carbon tax is the logical and necessary next step,” we said, “instilling incentives throughout the U.S. economy to replace fossil fuels with clean energy.”

Details about CLC’s proposal may be found on their site.

CLC renewed its call for a $40/ton carbon fee “in exchange for a rollback of Obama-era climate rules” in a May 9 New York Times op-ed, The Business Care for the Paris Climate Accord, co-authored by Shultz and Halstead.

3. Niskanen Center

A signal development since 2014 has been the emergence of the Niskanen Center as a leader in conservatives’ (and especially libertarians’) interest in carbon taxing.

The center’s founder-director, Jerry Taylor, was an energy policy analyst at the Cato Institute, where he helped forge Cato’s unflinching climate denialism (“I used to write skeptic talking points for a living,” he said in an April 2017 interview) until an immersion in climate science led him to a change of heart and a 180-degree turnaround on climate.

In March 2015, the Niskanen Center launched a full-scale assault on conservative obstruction of climate policy with a provocative paper by Taylor, The Conservative Case for a Carbon Tax. The paper argued that if conservative denial of climate science is grounded in ideological aversion to command-and-control regulation, as proposed in EPA’s proposed Clean Power Plan, conservatives should embrace and promote a revenue-neutral carbon tax as a more efficient, less burdensome, “free market” alternative and do so soon, because once established, EPA regulations will be almost impossible to uproot.

Taylor followed that paper with a series of bold blog posts further articulating his proposal, including these two in March 2015, Could Carbon Taxes Deliver a Double Dividend? and Debating the Carbon Tax, writing in the latter:

[C]onservatives ought to abandon their “just say no” policy towards addressing climate change. Global warming is real, industrial emissions are the main cause, and warming imposes risk that warrant a policy response… [C]arbon taxes are a far more efficient means of controlling greenhouse gas emissions than command-and-control regulation. [A] carbon tax at the levels presently discussed in Washington would not unduly burden the economy, and that’s particularly true once we consider the (non-climate) environmental benefits that would follow from the tax as well as the benefits of any offsetting tax cuts.

Taylor’s most recent (April 2017) paper, Debating Carbon Taxes With Oren Cass (And Bill Gates), is a lively and thoughtful survey of energy developments worldwide, particularly in the developing nations. In the lengthy (5,000 words) paper he tackles various precepts of conservative opposition to climate policy, e.g., unilateral U.S. action on climate is futile and self-defeating, and intentional abandonment of fossil fuels will consign poor nations and people to perpetual poverty. The paper is factual and filled with encouraging data on economic and technical progress in the solar and wind industries, and the clean-air co-benefits of phasing out coal, oil and gas.

Politicians

(Former Rep.) Bob Inglis, republicEn

During the fifth of his six terms as a member of Congress from South Carolina (Republican, 4th CD), in 2008, Bob Inglis introduced a bill proposing a revenue-neutral carbon tax whose revenue would reduce payroll taxes. Since leaving office in 2010 — he was primaried out by Tea Party favorite Trey Gowdy — Inglis has become a vocal advocate of carbon taxes as a free-market conservative alternative to regulations, subsidies and cap-and-trade systems. His organization republicEn unabashedly calls on “Conservatives [to] unify America to thwart climate warming.”

Inglis sounded a strongly optimistic — some might say naive — note in a March 2017 interview with Ensia.com, when asked whether the Trump administration might warm to the Baker-Shultz carbon tax proposal enunciated in Feb. 2017 by the Climate Leadership Council (see description above):

I think we could see Donald Trump embracing this if he could think of saying it this way at one of his rallies: “America is going to act first. We’re going to lead the world to a solution on climate change. We’re going to put a tax on carbon dioxide. We’re going to offset it with a dividend to the people or by other tax cuts and then we’re going to impose it on Chinese goods and everybody else’s goods unless they’ve got the same tax on carbon dioxide. If they want to sue us in the [World Trade Organization], well, I’m used to being in court. So, we’ll meet you there and beat you there. And as we beat you, you make your own decision to whether you want to put the same price on carbon dioxide at home or whether you want to keep on paying our tax on entry. Either way it’s fine with us.”

I know [passage of a carbon tax] seems improbable or even impossible. It looks impossible, but I think it’s going to go to the inevitable without ever passing through the probable.

Inglis consistently points to efficient markets as a bedrock conservative principle, arguing that for markets to work, fossil fuel prices must reflect true costs. In a January 2016 piece in the Daily Caller advocating a revenue-neutral carbon tax, he wrote:

Conservatives need a solution which doesn’t grow government, which trusts in the power of accountable marketplaces to deliver innovation and which empowers individuals in the liberty of enlightened self-interest to make their own decisions. Eureka!

Inglis also unabashedly praises climate science as a window into “the intricacies of this glorious creation.” That quote and these that follow are from an interview w/ Inglis published in the Dallas Morning News on August 29, 2014 under the headline, “Q&A: Bob Inglis on the conservative case for a carbon tax.”

Q: Isn’t a tax government intervention? Make a conservative case for a tax.

A: There is a role for government. It is simply being the honest cop on the beat that says to all fuels that you have to “own your own costs” so that the market can judge your product. We should eliminate all the subsidies. No more Solyndras. No more production tax credits for wind. No more credits for electric vehicles. No more special tax provisions for oil and gas. Level the playing field. The big challenge is reaching fellow conservatives and convincing them that the biggest subsidy of all may be to belch and burn into the trash dump in the sky — for free. That lack of accountability may be the biggest subsidy of them all.

Q: A lot of conservatives don’t accept climate change. Why do you?

A: I do because there is every reason to celebrate the science. Science is the process of discovery of the intricacies of this glorious creation. Is science settled? No. Science is never settled and we will never know all of the glories of the creation. But what we are discovering in climate science is that there is a risk that we can avoid from the creative innovation that comes from free enterprise. We have a danger and an opportunity. As a conservative, I say what a great opportunity to create wealth, innovate and sell innovation around the world.

Q: So why have conservatives rejected the science?

A: It has been presented as doom-and-gloom, this apocalyptic vision. Denial is a pretty good coping mechanism. The second reason is the assumed solution is a bigger government that taxes more, regulates more and decreases liberty. Given that, conservatives doubt whether we have a problem.

The Dallas Morning News piece has other revealing quotes as well. For more about Inglis, see The conservative case for a carbon tax (Houston Business Journal, 2/20/14), and Could Republicans ever support a carbon tax? Bob Inglis thinks so (Washington Post, 3/14/13).

Former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz

(Material in this sub-section should be viewed as precursors to Shultz’s co-sponsorship of the Climate Leadership Council’s 2017 issue brief discussed in detail above. Note that Shultz was one of the 32 signatories to the Carbon Tax Center’s November 2015 Call to Paris Climate Negotiators to Tax Carbon.)

Secretary Shultz, who served Pres. Nixon as Secretary of Labor and Treasury and OMB Director, and Pres. Reagan as Secretary of State, is a vocal supporter of the fee-and-dividend approach to carbon taxing.

In 2013, he and Nobel economics laureate Gary S. Becker published Why We Support a Carbon Tax in the Wall Street Journal. Their op-ed is a compelling and elegant articulation of the case for a revenue-neutral and steadily rising carbon tax.

In October 2015, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman contrasted Shultz’s climate concern to the denialism of leading GOP presidential hopefuls. An excerpt appears to the right.

In July 2014, Shultz participated in an M.I.T. Climate Lab hour-long Webinar on carbon pricing and taxing, alongside former Reps. Bob Inglis (see above) and Phil Sharp (D-IN), president of Resources for the Future. In a bravura performance, Shultz articulated the rationales for a carbon tax (and against cap/trade), including cap/trade’s price volatility and vulnerability to market manipulation, a carbon tax’s straightforwardness, and the success (and revenue-neutrality) of British Columbia’s carbon tax, as well as the general power of pricing and the insurance value of a carbon tax. Audio of the Webinar is available via this link.

And in March 2015, Shultz penned “A Reagan approach to climate change” (Washington Post), reminding readers of President Reagan’s bold response to scientific alarm about thinning of the Earth’s ozone layer which led to the Montreal Protocol, a treaty phasing out ozone-depleting chemicals. Shultz urged leaders to follow Reagan’s example by setting aside doubts and taking out a climate insurance policy before we get “mugged by reality.” Shultz concluded that robust funding of clean energy research and development, plus a revenue-neutral carbon tax, “starting small and escalating to a significant level on a legislated schedule” would “do the trick” and are the kinds of policies Reagan would advocate to avert climate disaster.

Writers and Pundits

David Brooks, New York Times and Weekly Standard:

On the PBS New Hour (February 20, 2015), Brooks critiqued President Obama’s State of the Union address as a missed opportunity to take a bold step by proposing a carbon tax. Pointing to bipartisan support from economists, Brooks observed that a carbon tax would “raise revenue, help the environment, and is an economic plus.”

Peter Van Doren, Cato Institute:

The one concept that all students, even those sleeping in the back of the lecture hall, learn from an introductory economics class is that prices matter… As prices increase, the quantity consumed goes down. So if fossil fuel combustion produces byproducts that cause negative health effects on third parties as well as changes in the temperature of the atmosphere, the obvious lesson from economics is to increase fossil fuel prices enough through taxation to account for these effects. Then firms and consumers will react to these prices in thousands of different ways, the net result of which is less aggregate fossil fuel combustion… [Yet] voters and their elected officials resist this simple insight and instead prefer to impose only energy efficiency standards on manufacturers of consumer appliances and automobiles. A singular emphasis on energy efficiency rather than prices has two important drawbacks. First, more efficient appliances and automobiles cost much more to achieve equivalent energy savings than a tax on fossil fuel consumption. This occurs because higher prices encourage all possible avenues of reducing energy consumption — which efficiency standards do not.

Excerpted from “When Prices Are Wrong, Markets Don’t Work,” in NY Times, “Room for Debate,” The Siren Song of Energy Efficiency, March 19, 2012.

Andrew Moylan, R Street Institute:

A conservative carbon tax has three key components: revenue neutrality, elimination of existing taxes, and regulatory reform. When combined, these policies would yield a smaller, less powerful government; a tax code more conducive to investment and growth; and the emissions reductions the law says we must achieve … [R]eform must devote every dime of carbon-tax revenue to reducing other tax rates or abolishing other taxes altogether. Turning on one revenue stream while turning off others is how we prevent growth in government… [A] $20 per ton tax on carbon dioxide emissions could generate roughly $1.5 trillion in revenue over ten years. That’s enough to allow for the complete elimination of several levies that conservatives rightly regard as structurally deficient or duplicative: capital gains and dividends taxes, the death tax and tariffs.

From How to Tax Carbon: Conservatives can fight climate change without growing government (American Conservative, 10/2/13).

Holman W. Jenkins, Jr., Wall Street Journal:

A straight-up, revenue-neutral carbon tax clearly is our first-best policy, rewarding an infinite and unpredictable variety of innovations by which humans would satisfy their energy needs while releasing less carbon into the atmosphere.

Excerpted from “Birth of a Climate Mafia,” July 2, 2014 (which, apart from this excerpt, is unrelievedly anti-climate reform).

Economists

Gregory Mankiw (Harvard): Perhaps the most widely-published advocate for higher fuel taxes in the economics profession is Gregory Mankiw, Harvard professor and former chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers (2003-2005), and former senior adviser to Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney. Mankiw was one of the 32 signatories to the Carbon Tax Center’s November 2015 Call to Paris Climate Negotiators to Tax Carbon., as well as a signatory to the Climate Leadership Council’s Feb. 2017 brief, The Conservative Case for Carbon Dividends.

Mankiw made the case for a carbon tax in a forceful NY Times op-ed, One Answer to Global Warming (Sept. 16, 2007) which we discussed on our blog. His 2006 Wall Street Journal op-ed pieces (Jan. 3 and Oct. 20) are among the many lively pieces available on Mankiw’s pro-fuel-tax blog, The Pigou Club Manifesto. (Economist Arthur Pigou, 1877-1959, articulated the concept of economic externalities along with corrective “Pigovian” taxes.) On Dec. 31, 2006 Mankiw reiterated his 2006 New Year’s Resolutions from his Jan. 3, 2006 WSJ piece, including:

I will tell the American people that a higher tax on gasoline is better at encouraging conservation than are heavy-handed CAFE regulations. It would not only encourage people to buy more fuel-efficient cars, but it would encourage them to drive less, such as by living closer to where they work. I will tell people that tolls are a good way to reduce traffic congestion — and with new technologies they are getting easier to collect. I will advocate a carbon tax as the best way to control global warming.

In a Sept. 16, 2006 post to his blog, Rogoff Joins the Pigou Club, Mankiw listed some three dozen other economists and pundits who have publicly advocated higher Pigovian taxes, such as gasoline taxes or carbon taxes. The list includes, in addition to several individuals mentioned here, such notables from economics, finance and journalism as Alan Greenspan, Gary Becker, William Nordhaus, Richard Posner, Anthony Lake, Martin Feldstein, Gregg Easterbrook and Lawrence Summers. (Links are included.)

Mankiw publishes a column every six weeks in the NY Times Sunday business section. In his June 1, 2008 column, The Problem With the Corporate Tax, Mankiw wrote:

I have a back-up plan for [Sen. McCain]: increase the gasoline tax. With Americans consuming about 140 billion gallons of gasoline a year, a gas-tax increase of about 40 cents a gallon could fund a corporate rate cut, fostering economic growth and reducing a variety of driving-related problems. Indeed, if we increased the tax on gasoline to the level that many experts consider optimal, we could raise enough revenue to eliminate the corporate income tax. And the price at the pump would still be far lower in the United States than in much of Europe.

In his Jan. 22, 2012 column, A Better Tax System (Instructions Included), Mankiw wrote:

Tax Bads Rather Than Goods: A good rule of thumb is that when you tax something, you get less of it. That means that taxes on hard work, saving and entrepreneurial risk-taking impede these fundamental drivers of economic growth. The alternative is to tax those things we would like to get less of. Consider the tax on gasoline. Driving your car is associated with various adverse side effects, which economists call externalities. These include traffic congestion, accidents, local pollution and global climate change. If the tax on gasoline were higher, people would alter their behavior to drive less. They would be more likely to take public transportation, use car pools or live closer to work. The incentives they face when deciding how much to drive would more closely match the true social costs and benefits. Economists who have added up all the externalities associated with driving conclude that a tax exceeding $2 a gallon makes sense. That would provide substantial revenue that could be used to reduce other taxes. By taxing bad things more, we could tax good things less.

Although this and some other pronouncements by Mankiw concern gasoline taxes rather than carbon taxes, they could be considered bold by a close adviser to the Romney for President campaign.

Arthur Laffer (prominent economic adviser to President Reagan): In a New Hampshire Public Radio interview (10/19/11), and in “Economist Arthur Laffer proposes taxing pollution instead of income” (Vanderbilt Univ., 2/20/12), Laffer recommended a carbon tax with revenue used to cut income taxes, a swap that he argued would create jobs, improve economic output and reduce pollution. As Laffer and (then) Rep. Bob Inglis (R-SC) wrote in the New York Times (12/27/08):

Conservatives do not have to agree that humans are causing climate change to recognize a sensible energy solution. All we need to assume is that burning less fossil fuels would be a good thing. Based on the current scientific consensus and the potential environmental benefits, it’s prudent to do what we can to reduce global carbon emissions. When you add the national security concerns, reducing our reliance on fossil fuels becomes a no-brainer.

Yet the costs of reducing carbon emissions are not trivial. Climate change may be a serious problem, but a higher overall tax rate would devastate the long-term growth of America and the world.

It is essential, therefore, that any taxes on carbon emissions be accompanied by equal, pro-growth tax cuts. A carbon tax that isn’t accompanied by a reduction in other taxes is a nonstarter. Fiscal conservatives would gladly trade a carbon tax for a reduction in payroll or income taxes, but we can’t go along with an overall tax increase.

Laffer has said little about carbon taxes since around 2012, however, so it’s not clear if he currently (2017) qualifies as a carbon tax supporter.

Douglas Holtz-Eakin (American Action Forum): Holtz-Eakin, a senior policy adviser to the 2008 McCain campaign, is now president of the American Action Forum. In “Make a carbon tax part of reform effort” (Concord Monitor, 9/19/11), Holtz-Eakin argues for comprehensive tax reform to include a carbon tax so that more of the “true cost of burning a fossil fuel… in the form of air pollution, a negative impact on human health, harm to the environment or climate change [is a] component in economic decisions [such as] include whether to invest in a coal-fired power plant or a wind farm.” He suggests that carbon tax revenue be used to reduce the payroll tax, income tax and corporate tax rate. His organization, AAF, criticizes EPA regulation of greenhouse gases as costly and largely ineffective.

Irwin Stelzer (Hudson Institute): In “Carbon Taxes, An Opportunity For Conservatives” (2011) Irwin Stelzer, Senior Fellow and Director of the Hudson Institute’s economic policy studies group, wrote:

A tax on carbon… would reduce the security threat posed by the increasing possibility that crude oil reserves will fall under the control of those who would do us harm, either by cutting off supplies, as happened when American policy towards Israel displeased the Arab world, or by using the proceeds of their oil sales to fund the spread of radical Islam and attacks by jihadists.

A tax on carbon… need not swell the government’s coffers — if we pursue a second, long-held conservative objective: reducing the tax on work. It would be a relatively simple matter to arrange a dollar-for-dollar, simultaneous reduction in payroll taxes… Anyone interested in jobs, jobs, jobs should find this an attractive proposition, with growth-minded conservatives leading the applause.

In The Carbon Tax Has Something for Everyone (National Review, Dec. 29, 2014), Stelzer observed,

We have a unique opportunity to end the rancorous debate about climate change, a debate that is poisoning the air — the political air, that is — and inhibiting progress on two fronts: progress on addressing the possibility that we are on the road to a catastrophic warming of the globe, and progress on reforming our anti-growth tax structure, which is so inequitable that it is straining the public’s belief in the fairness of capitalism and what we like to call “the American Dream.” All we need do is stop pretending that the cost of carbon emissions is certainly zero, and that regulation provides a more efficient solution than the market.

Stelzer urged the Republican leadership in Congress to integrate a carbon tax into broader tax reform. He also pointed out that World Trade Organization rules enable a U.S. carbon tax to form the template for an effective global carbon tax structure, thereby breaking the UN climate policy gridlock.

In April 2015, writing in the conservative Weekly Standard, Stelzer reviewed and endorsed the new IMF book, “Implementing a U.S. Carbon Tax: Challenges and Debates” by Ian Parry, Adele Morris and Roberton C. Williams III. Stelzer remarked:

This collection of 13 essays finally provides empirical data—numbers, if you are an ordinary reader rather than a policy wonk—and analyses to help us to some reasoned conclusions. The broad conclusions to be drawn are that a carbon tax would: reduce emissions, raise revenues more efficiently than the taxes it might replace, and be relatively easy to implement, “a straightforward application of basic tax principles,” in the words of the volume’s sponsors, the International Monetary Fund, the Brookings Institution, and Resources for the Future.

Most recently, in A Deal Over Climate Change, also in the Weekly Standard, Stelzer opined that the Supreme Court’s 5-4 stay of the EPA Clean Power Plan could catalyze a bipartisan agreement to substitute a carbon tax for G.O.P. denialism and Democratic regulation. The Feb 2016 post’s subhead, “Why not a carbon tax? Both sides could do a lot worse,” encapsulated Stelzer’s belief that political forces would push the two sides toward such an accommodation.

Alan Viard, Resident Scholar, American Enterprise Institute: Former Dallas Federal Reserve economist (1998-2006) and former senior economist on the President’s Council of Economic Advisers (2003-04), Alan Viard is a regular contributor to the tax policy journal “Tax Notes.” In testimony to the Senate Finance Committee (2009), Viard explained the perverse effects of giving free allowances to polluters under cap-and-trade. When Senator Kerry asserted that “caps” are necessary to reduce emissions because polluters would “just pay” a carbon tax, Viard patiently and eloquently explained the bedrock principles of price elasticity that undergird both carbon taxes and cap-and-trade systems. Viard concluded by recommending a carbon tax with revenue used to reduce marginal tax rates.

Kevin Hassett, Director of Economic Policy Studies at the American Enterprise Institute: Conservative economist Kevin Hassett has long advocated a carbon tax as vastly preferable to costly regulations, subsidies or cap-and-trade schemes that induce energy price volatility and provide opportunities for manipulation and gaming by emissions traders. In early 2017, Hassett was named chair of President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisors.

Along with AEI colleagues Steven Hayward and Kenneth P. Green, Hassett authored “Climate Change: Caps vs. Taxes” (2007), a short and very readable article that deftly and systematically demolished the myths surrounding cap-and-trade with offsets while sketching the structure of a simple, effective carbon tax “shift.” The authors pointed out that many of the supposed advantages of emissions caps were based on assumptions about the success of EPA’s SO2 emissions trading program for power plants which was orders of magnitude smaller and simpler than the market that would need to be established for CO2 emissions. They argued that much of the EPA program’s apparent success in reducing SO2 emissions from power plants was due to simultaneous railroad deregulation which reduced the cost of delivering low sulfur coal strip-mined in the west. And they cautioned that a CO2 cap-and-trade program would induce price volatility, feeding speculators while starving legitimate investors in alternative energy.

The article neatly described the potential for a “double dividend” obtained by tax shifting: imposing taxes on CO2 pollution while using the revenue to reduce other distortionary taxes such as payroll, individual and corporate income taxes that dampen desirable economic activity. Hassett and colleagues suggested that such a carbon tax “shift” could improve the overall output of the economy even without considering climate benefits and thus represented a “no regrets” policy for conservatives who aren’t convinced of the danger of global warming. The article cited authoritative works by a range of leading economists including Yale’s William Nordhaus and Stanford’s Lawrence Goulder who also support carbon taxes.