Last weekend I bicycled to Long Beach, the Long Island town where I grew up. From the boardwalk, squinting into the sun, my riding partner Dave and I could make out a dozen freighters strung in a long line in the Atlantic Ocean, stacked up like aircraft waiting to land.

Giant ships offshore weren’t something you saw often from Long Beach in the last century. A solitary ordinary freighter was noteworthy. The dozen big ships last Saturday doubtless were a symptom of some downstream jam-up in the supply chain. But they were also a telltale of the vast expansion of global trade since globalization took rise several decades ago and made Asian factories the prime U.S. source of consumer goods.

Yellow circles mark cargo ships we saw strung out in the Atlantic. Photo: David Clark.

As coincidence would have it, both Dave and I had read Paul Krugman’s day-before NY Times column, Putin May Kill the Global Economy. “There are good reasons to worry that we’re seeing an economic replay of 1914,” Krugman wrote, referring to “the year that ended what some economists call the first wave of globalization, a vast expansion of world trade made possible by railroads, steamships and telegraph cables.”

Krugman envisages Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggering a replay of 1914. Not just the withdrawal from trade of Russian hydrocarbons and Ukrainian wheat but a “partial retreat from globalization,” i.e., a shrinkage in the “world-spanning supply chains” that now constitute global manufacture.

“What Putin has taught us is that countries run by strongmen who surround themselves with yes-men aren’t reliable business partners,” Krugman says, eyeing China above all. “So if you’re a business leader right now,” he writes, “surely you’re wondering whether it’s smart to stake your company’s future on the assumption that you’ll keep being able to buy what you need from authoritarian regimes. Bringing production back to nations that believe in the rule of law may raise your costs by a few percent, but the price may be worth it for the stability it buys.”

Who can disagree? What Krugman didn’t consider, though, is that the simplification and shortening of global supply chains as an antidote to irrational autocracy could become the political equivalent of carbon taxes on international shipping.

I’ve long harbored the notion that a sufficiently airtight regime of global carbon taxes might put a damper on world trade by making ocean-going shipping more expensive. Much trade would remain, of course, although the extent would depend on the magnitude of the tax. At the margin, though, the enormous movement of raw materials and goods across thousands of miles of ocean (or, more expensively, via air freight) would slow and perhaps even decline.

Krugman didn’t see deglobalization’s silver linings. We do.

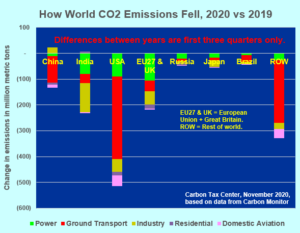

The resulting cut in global carbon emissions would be no small thing. Global shipping accounts for 2.2 percent of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, Time magazine reported recently, a figure that encompasses methane and other GHG’s and thus probably equates to 3 percent of worldwide CO2.

Deglobalization’s salutary effect on domestic manufacture might ripple even wider. Automation notwithstanding, relocating the making of goods for the U.S. market to the United States would raise factory employment and the number of stable, high-wage jobs. That in turn might restore a semblance of cohesiveness and meaning to the vast hollowed-out regions of middle America that since the Great Recession have turned in despair to opiates — pharmaceutical and political.

To be sure, this can sound very pie-in-the-sky, until you remember the pre-eminent role that dignified, well-paying manufacturing jobs played in U.S. progressive politics in the last century. Starting with Franklin Roosevelt and continuing until Reagan, labor and political organizing in America’s industrial unions played a vital part in furthering racial and economic equality through policies like progressive taxation and civil rights legislation, as historian Michael Kazin recounts in his latest book, What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party.

It’s not a huge stretch to triangulate from Kazin’s history of mid-century democratic capitalism and Krugman’s prognosis of deglobalization to imagine a resurgence in the kind of working-class progressivism that has largely been missing from the push for a Green New Deal. The victory last week through nontraditional, grassroots organizing by the worker-led Amazon Labor Union in Staten Island, NY, points in this direction. Over time, rising labor power accompanying renascent domestic manufacturing could help deliver the electoral wins and legislative energies needed to help the U.S. transit from fossil fuels to green energy.

Of course this is my take, not Krugman’s. What worries him about deglobalization isn’t the prospect that “wealthy, advanced economies will end up slightly poorer” as cheap imports recede. It’s the possible brake on economic advancement in “nations like Bangladesh that have made progress in recent decades [due to] access to world markets.”

Curiously for a columnist who frequently invokes climate change, Krugman didn’t mention the other, more dire prospect facing Bangladeshis: that continued “progress” in the form of fossil-fueled growth will lead to massive destruction of their country as the sea overwhelms it, monsoons fail, crops collapse, and desperate migrations of biblical numbers ravage the inland. Unless some thing or combination of things creates a different future.

In his 2020 novel, The Ministry For The Future, the “speculative fiction” writer Kim Stanley Robinson conjured a distinctive deus ex machina: “crash day” — an anonymous worldwide action causing jetliners to fall from the sky, killing passengers and crews but bringing down the curtain on hydrocarbon-fueled, climate-damaging aviation (zero-carbon airships take their place) and catalyzing, finally, a rapid global turning from fossil fuels.

After a decade of pining for a global carbon tax to reverse American deindustrialization, constrain global shipping, and then some, Krugman’s forecast of an autocrat-driven but nonviolent trade slowdown can look mighty attractive.

Addendum, May 9: A May 4 NY Times story, The Era of Cheap and Plenty May Be Ending, about the new logistical fragility of global supply chains, noted: “More firms reported moving their supply chains out of China to other countries, and American executives were more positive about bringing more manufacturing to the United States.”

The paper,

The paper,

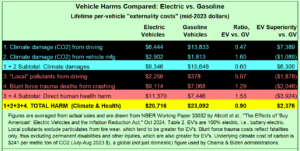

That EVs improve only modestly on GVs under reasonably broad social accounting is sobering. Yes, their climate benefit is substantial, around 1.7 to 1 (throwing in manufacturing CO2 with driving CO2). But that ratio is miles away from a clean sweep. And with NIMBYs, NEPA and other obstacles to a truly green grid, it’s not going to rise very much for a while.

That EVs improve only modestly on GVs under reasonably broad social accounting is sobering. Yes, their climate benefit is substantial, around 1.7 to 1 (throwing in manufacturing CO2 with driving CO2). But that ratio is miles away from a clean sweep. And with NIMBYs, NEPA and other obstacles to a truly green grid, it’s not going to rise very much for a while.