Commentator David Roberts, in Biden’s tax plan goes after the little fossil fuel subsidies, but not the big ones. (Direct subsidies don’t amount to much.), April 9.

Search Results for: revenue

Revenue-Neutrality Rises from the Dead

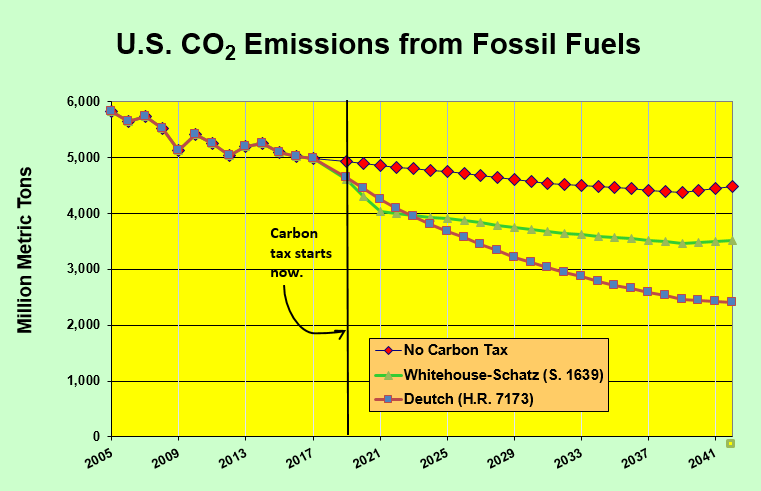

On Wednesday, Rep. Ted Deutch (D-FL) and a small bipartisan group of cosponsors introduced the strongest carbon pricing bill dropped into the Congressional hopper in years. H.R. 7173 closely follows the fee-and-dividend proposal long championed by Citizens’ Climate Lobby, employing not just the dividend template but the robust price trajectory.

The Deutch bill sets an initial tax rate of $15/metric ton, rising by $10/tonne annually thereafter. The increase rate would rise to $15/tonne if annual emissions targets are not met. All of the revenue, net of expenses, would go toward equalized dividends to all American households, based on household size, making the overall proposal revenue-neutral.

H.R. 7173 includes a border adjustment for both imports and exports, to protect the competitiveness of American manufacturing. And it restricts the government’s powers to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, at least for their impact on global warming — a limitation that may be more symbolic than substantive, given the modest emissions impact of President Obama’s signature Clean Power Plan, especially when compared to likely reductions from the new bill’s steep price trajectory.

The Deutch fee-and-dividend bill would surpass the most aggressive recent Democratic carbon tax after five years and would have twice the impact soon after.

The buzz thus far has focused on the bill’s initial cosponsors, two of whom are Republicans: Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA) and Francis Rooney (R-FL). This is not their first trip to the rodeo. Both also cosponsored a much weaker carbon tax bill introduced in July by Carlos Curbelo, who lost his bid for reelection. A third Republican, Dave Trott (R-MI), has since signed on. The two Democratic cosponsors are Charlie Crist (D-FL) and John Delaney (D-MD).

It’s important not to make too much of the bipartisanship on display here. Fitzpatrick, Rooney, and Trott represent an underwhelming 1.5% of the incoming Republican caucus in the House. More particularly, they constitute a mere one-seventh of the surviving Republican members of the all-too-quiescent Climate Solutions Caucus, which is losing most of its GOP contingent to defeat or retirement. Deutch and Curbelo were the founding chairs of the Caucus.

The larger substantive story here is the long-term impact of the Deutch proposal. His $15/tonne starting tax rate is lower than other bills introduced in this session, which range from $24/tonne (Curbelo) to $49/tonne (two Democratic proposals, S. 1639 and H.R. 4209). But the rates in those bills would generally rise by only 2% above inflation annually. Deutch’s proposal, though it starts from a lower base, would outstrip them in impact after just five years, with the differential only widening over time.

According to the Carbon Tax Center spreadsheet model, Deutch’s bill would reduce U.S. CO2 emissions below 2017 levels by 35% in a decade. The best of the Democratic proposals would see a smaller reduction of 25%.

The chances of any carbon tax bill passing in the next Congressional session are close to nil. It is hard to imagine such a proposal getting a floor vote in a chamber led by Sen. Mitchell McConnell (R-Coal Country, aka Kentucky). Even if it did, the veto pen of Donald Trump awaits. Nevertheless, the next two years will allow a debate within the Democratic Party over what its position will be on climate change in the 2020 campaign and, assuming that election goes well for them, in the 2021-22 Congressional session.

The Deutch bill is clearly a contender in that debate. And the more Republican cosponsors Deutch and CCL can recruit this session, the more likely it can become that a robust carbon tax, with revenues going back to American households, will be at least part of the answer.

The other major contender for a Democratic climate program right now is the as-yet-unspecified Green New Deal with major green infrastructure investments possibly funded by a carbon tax. Interestingly, the carbon tax bill with the most support in the House at present, with 21 cosponsors, would also devote most of the revenue to infrastructure, though not specifically green infrastructure. That’s H.R. 4209, the America Wins Act sponsored by longtime carbon tax champion Rep. John Larson (D-CT).

The important thing for carbon tax advocates to remember is that the best bill is the one that can pass. So may the best bill win.

I-732 is revenue neutral, to the best of anyone’s ability to forecast it.”

Does I-732 Really Have a “Budget Hole”?, Sightline Institute report on the I-732 Washington State carbon tax ballot initiative, Aug. 2.

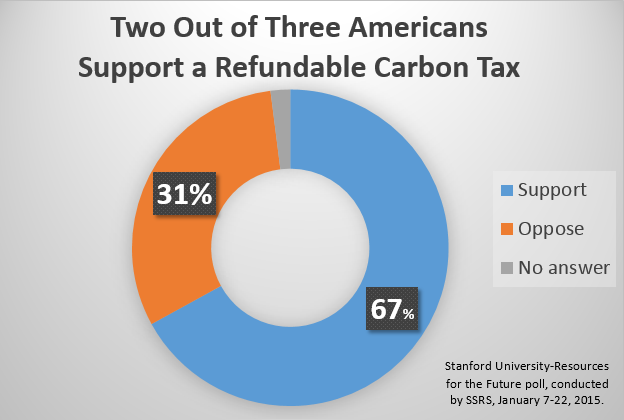

Carbon Tax Polling Milestone: 2/3 Support if Revenue-Neutral

For more years than I care to count, the Carbon Tax Center beseeched pollsters to take Americans’ temperature on revenue-neutral carbon taxes. Time and again we explained that polling about carbon taxes had to incorporate the option of returning revenues to households ― as most carbon tax bills would do. Otherwise, the tax came off as all stick and no carrot, and about as appealing to most folks as a cold shower.

Finally, a Stanford University-Resources for the Future poll asked that question. The results, released today, show that two-thirds of Americans support making corporations pay a price for carbon pollution, provided the revenues are redistributed, i.e., made revenue-neutral. The poll’s finding is the most powerful indication yet that the public is warming to carbon taxation as the premier policy for combating climate change.

Stanford and RFF commissioned the polling firm SSRS to interview 1,023 U.S. adults on climate-related issues in January. Two findings from the poll — that Americans of Hispanic descent are particularly climate-concerned, and that half of Republicans would favor a presidential candidate who supports fighting climate change — led to front-page New York Times stories. (Click here for the story on Hispanics and here for the story on Republicans.) The full poll was made publicly available today at a briefing at the National Press Club in Washington.

Stanford and RFF commissioned the polling firm SSRS to interview 1,023 U.S. adults on climate-related issues in January. Two findings from the poll — that Americans of Hispanic descent are particularly climate-concerned, and that half of Republicans would favor a presidential candidate who supports fighting climate change — led to front-page New York Times stories. (Click here for the story on Hispanics and here for the story on Republicans.) The full poll was made publicly available today at a briefing at the National Press Club in Washington.

The poll was supervised by RFF university fellow Jon Krosnick, who has been polling Americans on climate change for two decades as head of Stanford’s Political Psychology Research Group. Its section on carbon taxation included these two questions: [Read more…]

[A] pivotal moment is approaching in Washington, one in which overarching tax reform actually might take place. Such a moment could provide political cover for [a revenue-neutral carbon] tax.”

Jeffrey Ball, Facing the Truth About Climate Change, The New Republic, Feb. 4.

‘We were told it would destroy the economy and we’d never get elected again, but we’ve won two elections since [our carbon tax] was enacted’ five years ago, according to Mary Polak [British Columbia’s] Minister of Environment. ‘It’s the revenue neutrality that really makes it work. We collected C$1.2 billion last year and a little bit more was returned.’ “

Journalist James Fahn, in At Climate Talks in Lima, Only the Arguing Remains the Same (a post embedded in Andrew Revkin’s Dot Earth blog, Dec. 14).

A straight-up, revenue-neutral carbon tax clearly is our first-best policy, rewarding an infinite and unpredictable variety of innovations by which humans would satisfy their energy needs while releasing less carbon into the atmosphere.”

Wall Street Journal columnist Holman W. Jenkins, Jr. in Birth of a Climate Mafia, July 2.

Revenue-Neutral: Yes or No?

A “robust” carbon tax — one high enough to significantly change fuel incentives, drive innovation and transform our energy system and culture — is going to generate large amounts of revenue.

Fossil-fuel burning in the U.S. now (pre-pandemic, 2019) emits around 5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide a year. A carbon tax set at the threshold of robustness — $50 per metric ton — would generate roughly $250 billion a year in new tax proceeds. That’s a significant figure by any measure. It equates to 6-7 percent of total U.S. tax proceeds (currently $3.86 trillion). Spread among the country’s 128.5 million households (as of 2017), it’s $1,950 a year.

Not surprisingly, “what to do with the carbon tax revenue” is the most contentious issue surrounding carbon tax proposals, especially for possible carbon taxes at the federal level where the tax rate could be higher and political divisions are starker.

Revenue-Neutral Carbon-Taxing

Revenue-neutral means that government retains little if any of the tax revenues raised by taxing carbon emissions. Instead, the revenues are returned to the public; with, perhaps, small amounts utilized to assist communities dependent on fossil-fuel extraction and processing to adapt and convert to low- or non-carbon economies.

There are two overlapping but nonetheless disparate reasons for structuring a carbon tax to be revenue-neutral.

One is to appeal to (or appease) voters and elected officials who claim to abhor government and thus don’t want to swell its coffers.

The other is to counter or at least minimize the natural regressivity of carbon taxes by returning revenue in a way that protects the less affluent, while preserving the tax’s price-incentive to reduce emissions. (Keep in mind that wealthier households use more energy, since they generally drive and fly more, have bigger (and sometimes multiple) houses, and buy more stuff that requires energy to manufacture and use.)

There are two primary approaches to returning or recycling the tax revenues.

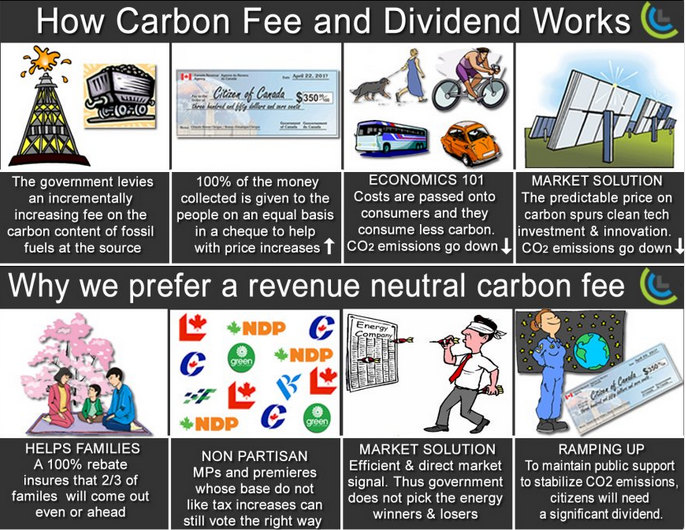

One approach, discussed below in detail, returns revenues directly through regular (e.g., monthly) “dividends” to all U.S. households or residents. Every resident or household receives an equal, identical slice of the total carbon revenue “pie.” In this approach, which adherents at Citizens Climate Lobby call fee-and-dividend, each individual’s carbon tax is proportional to his or her fossil fuel use, creating an incentive to reduce; but everyone’s dividend is equal and independent of his or her usage, preserving the conservation incentive. Alaska’s dividend program has provided residents with annual allotments from the state’s North Slope oil royalties for three-and-a-half decades.

In the other revenue-return method, each dollar of carbon tax revenue triggers a dollar’s worth of reduction in existing taxes such as the federal payroll tax or corporate income tax — or, on the state level, sales taxes. As carbon-tax revenues are phased in (with the tax rates rising steadily but not too steeply, to allow a smooth transition), existing taxes are phased out. While this “tax-shift” is less direct than the dividend method, it too ensures that the carbon tax is revenue-neutral. It offers other important benefits, as well; for example, reducing payroll taxes could stimulate employment.

To repeat: each individual’s receipt of dividends or tax-shifts is independent of the carbon taxes he or she pays. That is, no person’s benefits are tied to his or her energy consumption and carbon tax “bill.” This separation of benefits from payments preserves the carbon tax’s incentive to reduce use of fossil fuels and emit less CO2 into the atmosphere. (Of course, it would be extraordinarily cumbersome to calculate an individual’s full carbon tax bill since to some extent the carbon tax would be passed through as part of the costs of various goods and services.)

Revenue-neutrality not only protects the poor, it’s also politically savvy since it offers a way to blunt the “No New Taxes” demand that has held sway in American politics for decades. Returning the carbon tax revenues to the public would also make it easier to raise the tax level over time, a point made nicely by McGill University professor Christopher Ragan in a 2008 Montreal Gazette op-ed, and subsequently borne out by the experience in British Columbia where a revenue-neutral carbon tax was ramped up in four annual increments; that tax remains politically popular and is driving down emissions.

In any event, either of the two “revenue return” approaches — carbon dividends and tax-shifting — can make carbon taxes income-progressive. Because income and energy consumption are strongly correlated, most poor households will get more back in their carbon dividends or via tax-shifting than they will pay in the carbon tax. The overall effect of a carbon tax could thus be equitable and even “progressive” (benefiting lower-earning households).

Revenue-Positive Carbon-Taxing (Investing in Alternatives)

It may seem axiomatic that carbon-tax revenues should fund renewable energy or efficiency upgrades. And that approach always polls well, making it politically attractive.

Nevertheless, climate and energy realities indicate that only a robustly-rising carbon tax can deliver the deep and broad CO2 emission reductions needed to avert climate disaster. Building public support and maintaining the fairness needed for such a substantial carbon tax can most easily be done if all or nearly all of the carbon-tax revenue is returned to taxpayers. See “Making a carbon tax income-progressive” and our blog post: “Which Carbon Tax: Robust or Miniature? (July 7, 2013)”

Dividends

(a/k/a Carbon Dividends or “Green Checks”)

One revenue treatment that is both income-progressive and appealingly straightforward is to return the revenues equally to all U.S. residents. This so-called “dividend” would be a national version of the Alaska Permanent Fund, which since the 1970s has annually sent all state residents identical checks drawn from earnings on investments made with the state’s North Slope oil royalties. (For a federal carbon tax, the “dividend” checks should be provided quarterly or monthly to keep households ahead of the budget treadmill.)

The dividend approach was so attractive and elegant that the nation’s most energetic and active advocacy organization for carbon taxes has organized around it. That’s the Citizens’ Climate Lobby, which calls its approach carbon fee-and-dividend.

Fee-and-dividend explained, Canadian style. Hat tip to @scottsantens.

Nevertheless, it seems fair to say (and important to acknowledge) that by 2018, the second year of the Trump administration, fee-and-dividend has run out of political room. Not a single “sitting” (i.e., still in office) Republican member of Congress has publicly endorsed fee-and-dividend, even as a concept, let alone an actual bill. Yet the premise of fee-and-dividend has always been bipartisanship, since Democrats, with their preference for activist government, would accept a revenue-neutral carbon tax such as fee-and-dividend only if it delivered Republican votes.

For a decade, we wrote glowingly about fee and dividend — most recently in 2017 articles in The Nation and the Washington Spectator. We also praised the Climate Leadership Council’s “carbon dividend” proposal and advocacy in those two pieces and in numerous blogs (here, here, and here, inter alia). But as we wrote in June 2018, we believe that the time for carbon dividend proposals has probably passed. We wrote:

The [political] center to which Baker-Shultz (CLC) and fee-and-dividend (CCL) were designed to appeal barely exists. It’s not just that no sitting Republican has endorsed Baker-Shultz or indeed fee-and-dividend in any form. It’s also that the Democratic majority that will be needed to pass a carbon tax bill appears unlikely to rally around a revenue-neutral carbon tax, whether it’s organized as fee-and-dividend or some form of tax swap.

Economic Progressivity of Fee-and-Dividend

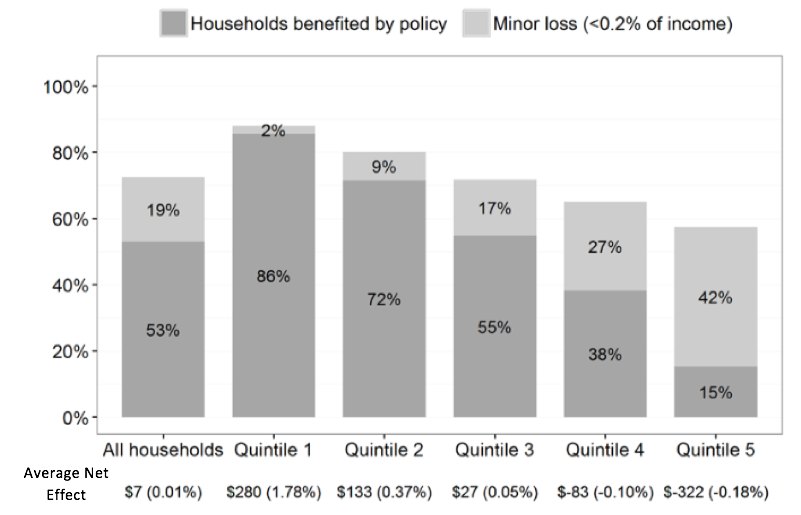

In 2016 CCL released a detailed paper examining how a carbon fee-and-dividend would impact U.S. households. The study took into account geographic variations in electricity sources and gasoline use and drew on a database of carbon intensity of expenditures for 5.8 million households to analyze the net effect of returning revenue to households on a modified per capita basis. Here are the major results:

- 53% of households (and 58% of individuals) would receive more in dividend payments than they would spend due to higher fossil fuel prices.

- Another 19% of households would incur only a slight loss, defined as a net loss no larger than one-fifth of one percent of pre-tax income.

- Nearly 90% of households below the poverty line would benefit an average of $311, an increase of roughly 2.8% of pre-tax income.

- In contrast, the net loss for the top quintile of households would average $-322 or only -0.18% of pre-tax income.

Notably, these findings support a dividend plan’s ability to transform a carbon tax into a progressive policy that neutralizes the burden that lower-income households would otherwise face, directly and indirectly, due to higher fuel prices. CTC advocates a progressive distributional outcome for both pragmatic and ethical reasons: pragmatically, because a carbon tax will require broad, sustained, public and political support; and ethically, because it’s not tenable to solve the climate crisis on the backs of those who can least afford it.

A Caveat — CBO’s “haircut”

The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office routinely “scores” members’ bills for their prospective impact on tax revenues. To streamline its analyses, CBO long ago settled the so-called “CBO haircut” by which it assumes that one-quarter of indirectly raised revenues would need to be allocated from the tax proceeds in question in order to make up for reduced tax revenues collected from conventional sources such as personal or corporate income taxes. But modeling of carbon tax proposals consistently finds that when revenue is strategically returned by reducing other taxes that tend to slow down economic activity, the net negative impacts are much lower than CBO’s 25% assumption and in some cases may be eliminated altogether. While returning revenue as “dividends” (which economists call “lump-sum rebates”) offers less potential to reduce economic drag than tax shifts, CBO’s assumption still seems like an over-estimate.

In any event, rigid application of the 25% CBO haircut could, on paper at least — and, likely, in Congressional deliberations — limit the carbon tax revenue perceived to be available for “dividends” to 75%. Yet even with this reduced fraction of revenue, returning carbon tax revenue via a direct dividend represents a simple and income-progressive means to make carbon taxes distributionally fair; though with the haircut, the share of households reaping a net benefit via an equal 75% dividend would be lower than the 58% of individuals mentioned above.

Related CTC blog posts

- The Carbon Tax Revenue Menu (6/10/2011)

- Should Carbon Pricing Advocates Support the Cap-and-Dividend Bill? (12/2/2010)

- Scientist James Hansen Proposes “People’s Climate Stewardship Act”: A Simple Carbon Fee with Revenue Returned to Americans (4/25/2010)

- Progressive Democrats Say: “Cut Out Wall Street — Price Carbon Directly and Recycle Revenue to Households.” (10/20/2009)

- Back to Plan A: The Revenue-Neutral Carbon Tax (7/6/2009)

Related news reports and opinion pieces

- Alaska’s Permanent Dividend Fund — A policy ripe for export (Bangor Daily News, 6/20/2011)

- James Hansen Rails Against Cap-and-Trade in Open Letter, Advocates Fee-and-Dividend to Reduce Carbon Emissions (The Guardian, 1/12/2010)

- Cap and Fade (James Hansen, NYT op-ed, 12/6/2009)

- How CBO budget scoring devalues efficiency (Dave Roberts, Grist 10/15/2009)

Cogent opinion pieces by dividend proponent James K. Boyce (U-Mass, Amherst)

- Does Biden’s insurance policy for the climate go far enough? (The Hill, 2/26/2021)

- Carbon Dividends: The Bipartisan Key to Climate Policy? (Institute for New Economic Thinking, 2/17/2017)

- The Carbon Dividend (New York Times, July 29, 2014)

Tax-Shifting

The distribution of carbon tax burdens creates an opportunity for “progressive tax-shifting,” in which a portion of carbon tax revenue is dedicated to reducing regressive taxes such as the payroll tax (at the federal level) or sales taxes (at the state level). An early proponent of such a carbon tax shift was Al Gore, with his exhortation to “Tax what we burn, not what we earn.” Shifting taxes away from payroll and/or sales taxes and onto carbon pollution could raise, not lower, the after-tax incomes of a majority of below-median-income households, giving this approach a net progressive effect.

In addition to this potential progressive effect of tax shifting, a wide range of economists, [including Lawrence Goulder, Roberton Williams & Ian Parry, Gilbert Metcalf & David Weisbach, Alan Viard, Robert Shapiro, Donald Marron & Eric Toder] have concluded that use of revenue to reduce other taxes would improve the overall efficiency of the economy, for example, by removing burdens on work.

In October 2007, the Brookings Institution published a A Proposal for a U.S. Carbon Tax Swap — An Equitable Tax Reform to Address Global Climate Change by Tufts University economics professor Gilbert E. Metcalf, describing a national carbon tax paired with an income tax credit for payroll taxes paid. Metcalf assessed the impact of a tax of $15 per metric ton of carbon dioxide and five major greenhouse gases. Revenues would be used to credit payroll tax paid on the first $3,660 of earnings per worker. Metcalf showed that such a tax swap would be both revenue-neutral and distributionally-neutral. (Harvard professor and former Bush Administration economist Gregory Mankiw mentioned the Metcalf paper in a Sept. 2007 New York Times op-ed, discussed on our blog.) Rep. John Larson (D-CT) adopted Metcalf’s framework for his “America’s Energy Security Trust Fund Act,” discussed on our Bills page.

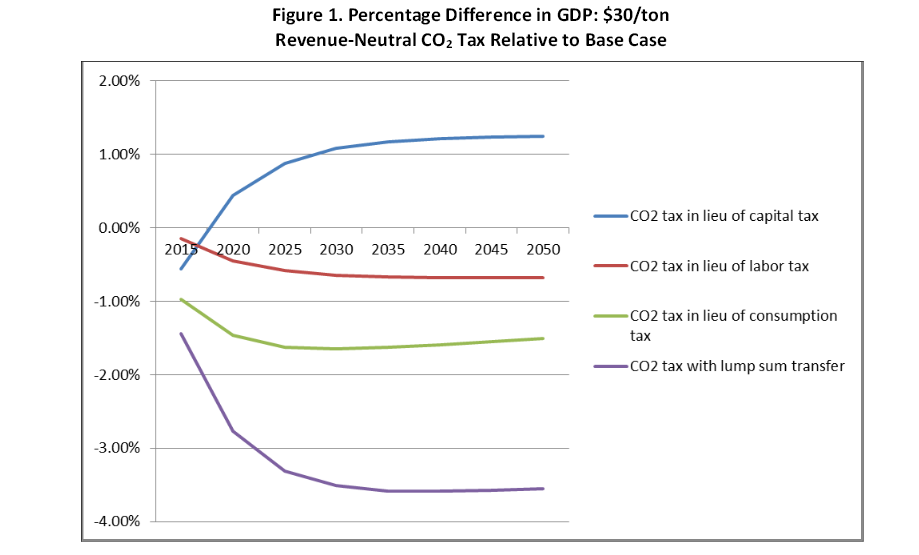

More recent analysis has confirmed the importance of carbon tax revenue wisely; using it to reduce other “distortionary” taxes can offer large enough efficiency benefits to reduce or even possibly eliminate the economic drag that a carbon tax would otherwise create. In Deficit Reduction and Carbon Taxes: Budgetary, Economic, and Distributional Impacts (2013) researchers from Resources for the Future found that using carbon tax revenue to reduce corporate income tax rates offers large enough efficiency benefits to more than overcome the efficiency loss of a carbon tax. The next best option is using revenue to cut wage taxes, while using revenue to cutting other consumption taxes is somewhat less efficient. Finally, refunding carbon tax revenue in a “lump sum rebate” (dividend) offers the least economic efficiency benefit.

More recent analysis has confirmed the importance of carbon tax revenue wisely; using it to reduce other “distortionary” taxes can offer large enough efficiency benefits to reduce or even possibly eliminate the economic drag that a carbon tax would otherwise create. In Deficit Reduction and Carbon Taxes: Budgetary, Economic, and Distributional Impacts (2013) researchers from Resources for the Future found that using carbon tax revenue to reduce corporate income tax rates offers large enough efficiency benefits to more than overcome the efficiency loss of a carbon tax. The next best option is using revenue to cut wage taxes, while using revenue to cutting other consumption taxes is somewhat less efficient. Finally, refunding carbon tax revenue in a “lump sum rebate” (dividend) offers the least economic efficiency benefit.

Reducing the top marginal corporate income tax rate has been articulated as a goal by leaders of both major political parties. In an effort to attract Republican interest, Rep. John Delaney (D-MD) has introduced a carbon tax measure that would devote half its revenue to corporate income tax reduction.

Nevertheless, the growing economics literature on carbon taxes suggests a strong a tradeoff between the efficiency benefits of using carbon tax revenue to cut taxes on capital (as the Delaney proposal would do) and the distributional benefits of cutting taxes on labor (as Rep. Larson’s proposal would).

Related CTC blog posts and articles

- British Columbia’s Carbon Tax Architects Speak (2015).

- The Carbon Tax Revenue Menu, outlining the benefits of various revenue options (2011).

- Carbon Tax Offers Super Powers to Super-Committee, discussing potential for a carbon tax to reduce the deficit (2011).

- Midterm Advice for Congress: Tax Carbon Instead of Jobs (Robert Shapiro, Huffington Post, 2010).

- Capitol Hill Briefing on Carbon Taxes Draws Overflow Crowd, Rep. John Larson (D-CT) led off CTC’s event, articulating the benefits of a taxing carbon pollution while cutting wage taxes (12/9/08).

Related journal articles and papers

- Taxing Carbon and Recycling the Revenue: Who Wins and Loses? (Donald Marron, Eric Toder, and Lydia Austin, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, Nov. 2015).

- Tax Policy Issues in Designing a Carbon Tax (Donald B. Marron and Eric J. Toder, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, 2014).

- Getting to an Efficient Carbon Tax: How the Revenue is Used Matters (Jared Carbone, Richard D. Morgenstern, Roberton C. Williams III, and Dallas Burtraw, Resources for the Future, 2014).

- A Carbon Tax in Broader U.S. Fiscal Reform: Design and Distributional Issues, Adele Morris (Brookings) and Aparna Mathur (American Enterprise Institute), C2ES, 2014).

- Carbon Tax Revenue and the Budget Deficit: A Win-Win-Win Solution? (MIT, 2012).

- The Potential Role of a Carbon Tax in U.S. Fiscal Reform (Brookings, 2012).

- Fiscal Policy to Mitigate Climate Change (IMF, 2012).

- How Climate Policy Could Address Fiscal Shortfalls (Adele Morris & Ted Gayer, Brookings, 2010).

- Addressing Climate Change Without Impairing the US Economy (Robert Shapiro, U.S. Climate Task Force, 2009).

- A Proposal for a U.S. Carbon Tax Swap (Gilbert Metcalf, Brookings, 2007).