"A significant portion of the business community would prefer a carbon tax" to a carbon cap-and-trade system, an official of a leading pro-business lobby group declared today.

In an interview on E&E TV, Margo Thorning, senior vice president and chief economist at the American Council for Capital Formation, honed in on one of the key advantages of carbon taxes over the competing cap-and-trade approach — price certainty:

An advantage of a carbon tax … is that an investor knows, given the projected … set of increases in carbon prices from one year to the next, he knows what the carbon price will be and he can factor that in to what kind of capital equipment he buys, what sort of transport fleet he puts in place, and it provides more certainty.

ACCF’s board has been called "a who’s-who in big business," with past or present directors from the American Petroleum Institute, American Forest & Paper Association, Edison Electric Institute and other pro-industry trade associations, thus lending corporate gravitas to Thorning’s remarks, excerpted (and slightly edited) here (Note: subscription probably required):

ACCF’s board has been called "a who’s-who in big business," with past or present directors from the American Petroleum Institute, American Forest & Paper Association, Edison Electric Institute and other pro-industry trade associations, thus lending corporate gravitas to Thorning’s remarks, excerpted (and slightly edited) here (Note: subscription probably required):

E&E TV: One of the bill’s ideas is to set

up a financial board of sorts that would oversee the new greenhouse gas market. What’s your take on setting up a board of regulators?

Margo Thorning: I think the idea of expecting regulators to know what the price of carbon should be is probably not very well grounded. It does serve as a backstop in that if prices got so high that producers and households were experiencing severe economic pain they could say, well, just go ahead and emit. But it creates uncertainty, because for someone trying to invest in new equipment, if they don’t know what the price of carbon will be, that adds to the risk of the investment. That’s the problem with a cap-and-trade system and that’s what’s happening in Europe. Investors don’t know what the price of carbon will be from one month to the next or one year to the next and it’s been very volatile. So that makes the

cost of capital higher, investment more uncertain, and produces less investment. An advantage of a carbon tax, if you want to impose some sort of penalty on carbon use, is that an investor knows, given the projected set of increases in carbon prices from one year to the next, he knows what the carbon price will be and he can factor that in to what kind of capital equipment he buys, what sort of transport fleet he puts in place, and it provides more certainty. And a carbon tax provides a stream of revenue for the government to spend on new technology or to pay for offsetting the burden on low income

individuals of higher energy prices.

E&E TV: So, if you were given the opportunity to write your own proposal of how the U.S. should

reduce emissions and not hurt itself economically, you’d go with the carbon tax?

Margo Thorning: I would go with the carbon tax and more incentives for new technology development.

E&E TV: So, if a cap and trade is not the way to go as you’re saying, why has the business community come out in support of a cap and trade?

Margo Thorning: Well, a significant portion of the business community would prefer a carbon tax and there’s beginning to be more discussion about that. I think one reason some in the business community have supported a cap and trade is they expect to make money on it. They’ve maybe made emission reductions or expect to be able to make emission reductions. They expect to be winners. On the other hand, new companies or companies that are expanding that need more credits will be losers. So the winners under a cap-and-trade system, for example in Europe, the big electric utilities have been winners because they’ve been able to pass forward to consumers the price of the carbon credit even though they were given those credits by the government. So people who expect to make money on it naturally are supportive.

* * *

ACCF’s clear acknowledgment of the price-certainty advantage of a carbon tax, coupled with its outspoken criticism of carbon cap-and-trade, follows the contours of the American Enterprise Institute’s June report contrasting the two approaches. The myth that business unanimously favors carbon cap-and-trade over carbon taxes (or monolithically opposes carbon pricing in the first place) is crumbling.

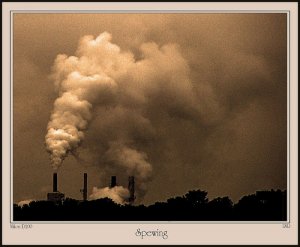

Photo: le_rez / Flickr.

Jurgen Hissen says

I think there’s a cap-and-trade drawback missing from your "problems with cap-and-trade" page.

Seems there is no good way to do the initial allocation of emissions credits. The choices are:

1. give credits away for free based on today’s pollution levels.

2. auction credits off

The first option means you’re rewarding everyone who’s been dragging their feet for the past decade.

The second option means that all polluters will immediately need to tie up huge amounts of capital in credits (instead of putting that capital into reducing their emissions)

James Handley says

Thorning’s last point is important:

Large, existing carbon emitters (utilities, heavy industry) would benefit from a cap & trade system, especially one that gave away emission rights to those already emitting. It would reward past pollution by allocating the future rights in proportion to past levels. That would disadvantage penalize new, more efficient (lower carbon-emitting) alternatives that would have to buy permits from the big polluters who got them free. Lots of opportunity for speculative gain for doing nothing except being big and being there first. (A bit like giving all the BLM land away to the biggest ranchers and mining companies.) A half-measure would be to auction emission rights (under a cap) so anyone could compete and it wouldn’t be a give-away. But by far the best is to tax (and gradually increase the tax on) emissions or the equivalent. Price stability, fairness and transparency. Not exactly "Liberty, Equality and Fraternity" but not bad.