Guest Post By Michelle Chan, Economic Policy Project Director, Friends of the Earth

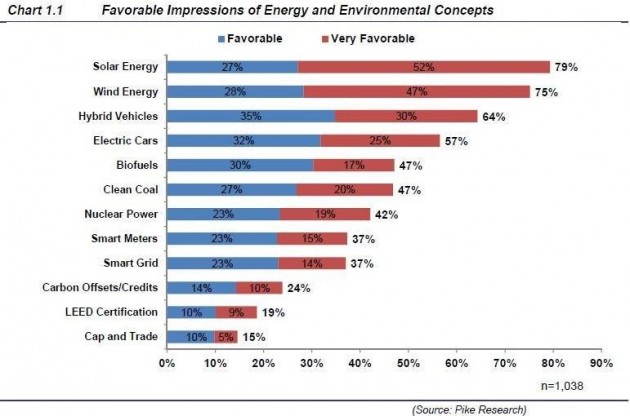

It’s been a bad month for carbon trading. The European Union Emissions Trading System (ETS), the world’s largest carbon market, barely crept back into operation after a four-week closure. Around the same time, California’s proposed cap and trade system went on hold after a Superior Court judge ruled that the rules creating a cap-and-trade system were adopted without proper analysis of alternatives. Adding insult to injury, Pike Research released a study which found that in a survey of 1000 Americans and their reactions to a variety of climate-related issues, offsets and cap-and-trade elicited the highest rates of “strongly unfavorable” or “somewhat unfavorable” impressions.

Some have blamed cap-and-trade’s woes on anti-climate propaganda and retrograde politicians. Actually, the fault is in cap-and-trade itself; while the concept may appear elegant in an Econ 101 textbook, it is spectacularly unsuited for its supposed purpose of capping and reducing carbon emissions.

To see why, look no further than the troubles besetting the ETS. Only six of the thirty European carbon registries have been permitted to re-open after the EU halted trading in the wake of the theft of millions of euros worth of allowances from national registries. This scandal occurred on the heels of several others. In November, Swiss cement maker Holcim reported that 1.6 million euro of allowances were stolen from its account; only a fraction of them have been tracked down and returned. Last year, Europol reported that fraudulent carbon traders had shortchanged several national governments to the tune of 5 billion euro. In fact, Europol estimated that for a time 90% of trading volume on the Paris-based BlueNext carbon exchange was tied to fraudulent activities.

These are not a new market’s “growing pains”; rather, these scandals were (and are still) all too predictable. Today’s scandals involve opportunists exploiting immature trading structures, systems and rules. Tomorrow’s scandals are likely to involve more sophisticated gaming around complex and unwieldy trading programs, with offsets posing the most risk for fraud and corruption. And as the global carbon market expands further and Wall Street gets fully involved, it will surely suffer from the distorting impacts of unnecessary speculation and excessive financialization.

The root of the problem is that carbon trading entrenches the interests of those who profit from the selling and trading of credits and allowances, at the expense of actually reducing emissions. This dynamic inevitably exacerbates conflicts of interest and heightens corruption risks. It also intensifies regulatory capture — the process by which regulators end up advancing interests of the sector they are supposed to oversee, rather than protecting the public interest.

One poster child for regulatory capture in carbon markets is Christiana Figueres, who is both executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and an advisor at C-Quest Capital, an offset developer. The larger problem is the revolving door between regulators and industry, a classic way in which corporations wield influence over regulators; and the outsized resources of corporate lobbyists. Already, associations such as the International Emissions Trading Association (whose members were among those charged by the UK police for conspiracy to commit tax fraud) have lobbied against stricter derivatives regulations and have blasted UN officials for not approving offsets fast enough.

While mainstream green groups appear largely unconcerned about the pitfalls of carbon trading, the environmental justice community is finely attuned to the downsides. The Superior Court judge ruling in California, which for the time being has stopped the California Air Resources Board from implementing California’s proposed carbon trading system, was the result of a suit brought not by Big Oil but by environmental justice organizations which oppose carbon trading because of its likely localized health impacts. For example, under a carbon trading system, a refinery in Wilmington, CA, near Long Beach, could keep emitting carbon along with the associated toxic co-pollutants by purchasing carbon permits or offsets, instead of cleaning up its operations. “Fenceline” communities, which are almost always lower-income communities of color, already suffer from cumulative environmental health hazards, and carbon trading could exacerbate pollution hotspots as companies delay upgrading their dirtiest operations.

Indeed, the “efficient markets” theory behind cap-and-trade, and carbon taxes for that matter, posits that pricing carbon will help allocate financial resources in ways that most efficiently reduce carbon — meaning the cheapest emissions cuts will be made first. But if carbon pricing isn’t accompanied by stringent regulation of local emissions (which after 40 years aren’t well-implemented in practice – just ask the folks in Wilmington), it leaves fenceline communities suffering the brunt of continually spewing toxic pollutants.

While advocates may differ over whether pricing carbon should be the centerpiece of greenhouse gas reduction policies, it has an important role to play in complementing other foundational strategies such as performance standards, regulations, urban planning and public infrastructure investments like mass transit. And when it comes to carbon pricing, carbon fees or taxes, rather than cap-and-trade, are the vastly superior option. One look at the malfeasance that has plagued carbon trading in Europe, the gaming and excessive speculation of derivatives traders, or the lack of environmental integrity in the offsets markets, and it’s easy to understand why so many people – from Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz, to fenceline communities, to ordinary Americans — are skeptical of cap-and-trade.

Daniel Jones says

A major argument in this post is that flaws in offset trading systems, including both direct theft through computer system hacking and manipulation of prices, provide a reason for not allowing offsets.

NASDAQ and other stock trading systems have been subject to hacking and potential theft of stocks (see for example, “Hackers Penetrate Nasdaq Computers”, Wall Street Journal, February 5, 2011).

Wheat and other commodities have been subject to price manipulation for years, with severe consequences especially for developing countries in 2008. In 2010, the chocolate market was cornered (see, “Trader’s Cocoa Binge Wraps up Chocolate Market”, NY Times, July 24, 2010).

Despite these problems, we rarely hear people propose that high tech stocks, wheat, and chocolate not be produced. Rather, we look for ways of regulating and supervising markets better and of safeguarding the computers of trading systems.

Is there some fundamental difference between carbon offsets and stocks, wheat, and chocolate when in comes to ensuring or promoting the integrity of their market?

I don’t see reason for banning a product like offsets simply because it faces the same threat of theft, manipulation, and fraud faced by many other commodities.