In recent years the Bay Area-based Breakthrough Institute (BI) has staked out a place in the climate and energy debate by arguing that the way to decarbonize U.S. and world energy is to spur technological innovation — not through the “stick” of carbon taxing but by the “force multiplier” of federal R&D. BI’s current poster child for this approach is hydraulic fracturing (fracking), although the Institute also backs wind and nuclear power and photovoltaic solar cells.

BI’s latest salvo, a report released a few days after the elections, made sweeping claims for the superiority of fracking over pricing carbon emissions:

Over the last four years, emissions in the United States declined more than in any other country in the world. Coal plants and coal mines are being shuttered. That’s not from increased use of solar panels and wind turbines, as laudable as those technologies are. Rather it’s due, in large measure, to the technological revolution allowing for the cheap extraction of natural gas from shale. By contrast, Europe, with its cap and trade program, and price on carbon, is returning to coal-burning.

BI president Michael Shellenberger and board chair Ted Nordhaus sounded the same theme in this letter in the New York Times on Nov. 15:

Germany and other European countries have put a price on carbon, through their cap-and-trade system, but are returning to coal burning anyway. A carbon tax can play a useful role as a way to raise money for public investments in innovation, but the suggestion that a carbon tax would result in the kind of innovation that is allowing natural gas to replace coal is to ignore the real-world evidence.

A lot of assertions and assumptions are packed into those two passages. Here are the key ones:

- U.S. greenhouse gas emissions have fallen considerably since 2007 or 2008.

- Solar and wind had little or nothing to do with that drop.

- No country cut greenhouse gas emissions more since 2007 or 2008 than the U.S.

- Europe has a price on carbon.

- Europe is returning to coal-burning.

- A carbon tax won’t contribute to low-carbon innovation.

Assertion #1 isn’t in dispute — we all know that the fracking boom has enabled relatively low-carbon methane gas to make big inroads into coal’s share of U.S. electric power generation. And #6 is more a question of belief — and how high a carbon tax is assumed — than of empirical validation. But assertions #2, #3 and #5 are eminently quantifiable, and so, as we’ll see below, is #4. I wrote to Shellenberger and pressed him on these points. His replies were collegial, but at variance with empirical data.

Breakthrough Claim #2: Solar and wind contributed little or nothing to the drop in U.S. GHG emissions over the last four years.

Or, in BI’s own words: “Coal plants and coal mines are being shuttered. That’s not from increased use of solar panels and wind turbines.”

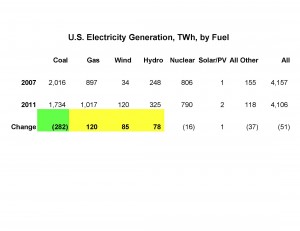

Hardly. Verification of wind power’s strong contribution to displacing coal can be seen in the table comparing U.S. electricity generation in 2011 and 2007. Electricity from coal-fired power plants, the single largest source of U.S. CO2 emissions as well as the mainstay of our power supply, fell by 282 TWh, a decrease equivalent to nearly 7% of all U.S. electricity production in either year. (A terawatt-hour is a billion kWh.) Because total U.S. electricity use in 2011 was little changed from 2007, the drop in coal-fired power had to be made up by ― indeed, was caused by ― increases in other sources. As the table shows, gas-fired generation was the largest source of increased electric output, growing by 120 TWh. But wind was a strong second. Its gain of 85 TWh over the same period was 70% as great as the gain from natural gas. (Hydro also grew substantially, but its increase was an artifact of weather variability in the form of deeper snowpack. Note also that solar-generated electricity is relatively tiny.)

To be sure, full-year 2012 data will almost certainly show a further big dip in coal-fired electricity, with the lion’s share of that one-year change (2011 to 2012) attributable to increased use of natural gas. Yet wind’s contribution to the ongoing drop in coal-fired electricity also increased in 2012, albeit by considerably less than the contribution from gas. Moreover, each time a kWh of coal is replaced by wind, CO2 emissions from generating that kWh fall by 100%, whereas the drop when the coal-fired kWh is replaced by gas is only 40-65% (depending on whether the gas-fired kWh comes from a traditional steam-cycle generator or a newer combined-cycle generator). Nor do wind turbines entail mining “natural” gas and the consequent release of climate-destabilizing “fugitive” methane and black carbon. All told, the Breakthrough Institute’s dismissal of wind power as a factor in reducing CO2 from the U.S. electric power sector is both mistaken and incongruous.

Breakthrough Claim #5: Europe is “returning to coal-burning.”

To see if Europe is indeed “returning to coal,” I registered (at no charge) with Enerdata, authoritative compilers of country, region and world data on energy production and consumption. These data are from Enerdata’s table, “Coal and Lignite Domestic Consumption in Europe (millions of metric tons)”:

2007: 1,009

2008: 962

2009: 889

2010: 897

2011: 937

(“Europe” comprises Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany F.R., Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, Iceland, ex Yugoslavia, Albania.)

Rather than a return to coal, the data show a dip from 2007-08 to 2009, followed by a slight rise to 2011. Even if the 2011 rise has continued into 2012, it likely amounts to no more than a return to the level of 2007-08. In short, Europe’s coal consumption shows no clear trend.

Beakthrough Claim #3: No country cut greenhouse gas emissions more since 2007 or 2008 than the U.S.

True enough, if Breakthrough was measuring cuts in tons — after all, the U.S. is the World’s second largest CO2 emitter, with nearly triple the emissions of third-place India and fourth-place Russia. But not necessarily true on a percent basis.

Again referencing Enerdata, from 2007 to 2011, CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel combustion decreased by 7.4% in the U.S. and by slightly more, 8.5%, in the 33 countries that Enerdata collects as “Europe.” (See Enerdata table: CO2 emissions from fuel combustion (MtCO2).) While the relative positions of the U.S. and Europe may switch when the data are extended to 2012 (for declines in CO2, though not necessarily for other GHG’s associated with gas fracking), neither entity has a clear lead on the other.

We come now to the final point at issue, and, perhaps, the most central to the Carbon Tax Center’s dispute with the Breakthrough Institute:

Breakthrough Claim #4: Europe has a price on carbon.

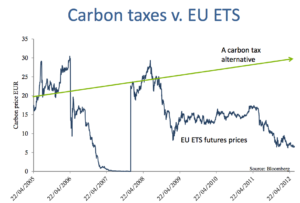

It appears that a “price on carbon” is a rhetorical device wielded by the Breakthrough Institute to discredit carbon taxing. At the Carbon Tax Center, we’ve said all along that a carbon tax must be (i) robust (not minuscule), (ii) rising, and (iii) transparent. The “price on carbon” that Nordhaus and Shellenberger claim “Germany and other European countries have implemented through their cap-and-trade system” has been none of those three things, as this graphic shows.

The graph is by Dieter Helm, professor of energy policy at Oxford, and is from his recent presentation to the Bruegel Energy and Climate Exchange, “Climate change and EU policy — why has so little been achieved?” It shows the first seven years’ worth of CO2 futures prices under the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). The price has varied from 30 euros per ton of CO2 down to zero. As the graph shows, the price’s course over time more closely resembles a Mandelbrot fractal than a clear trajectory that would communicate to entrepreneurs and individuals the rewards from moving to low-carbon behaviors and innovations (and the penalties from maintaining the status quo).

The graph is by Dieter Helm, professor of energy policy at Oxford, and is from his recent presentation to the Bruegel Energy and Climate Exchange, “Climate change and EU policy — why has so little been achieved?” It shows the first seven years’ worth of CO2 futures prices under the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). The price has varied from 30 euros per ton of CO2 down to zero. As the graph shows, the price’s course over time more closely resembles a Mandelbrot fractal than a clear trajectory that would communicate to entrepreneurs and individuals the rewards from moving to low-carbon behaviors and innovations (and the penalties from maintaining the status quo).

Moreover, it’s not enough for emissions to simply decline, as they have in both Europe and the U.S., due in considerable part to the economic slowdown that has afflicted both. The declines in carbon emissions must be sustained and massive. The heart of the climate solution remains what it has always been: a steadily rising U.S. carbon tax with border tax adjustments that motivate China and other growing emitters to implement their own carbon taxes (else the U.S. will collect their carbon tax revenues via carbon-content tariffs).

A wildly fluctuating carbon price such as the one delivered by the EU ETS may be a handy rhetorical device for the Breakthrough Institute and other carbon tax opponents. But it in no way qualifies as meaningful and should not be wielded as a means to discredit genuine carbon taxing.

David F Collins says

The collection, organization, analysis and presentation of data on GHG emissions is crucial; otherwise, implementation of a proper Carbon Tax is iffy while selling it is more difficult. For instance, there is considerable evidence of CH₄ emissions through losses in transmission, from upstream of the wellhead and downstream to the point-of-use. A simple Carbon Tax application would ignore such losses if the data are ignored. A valid question is whether the regular tax rate or a stiff penalty should apply. If the CH₄ is used to produce plastics feedstocks or fertilizer (inter al.), there is some benefit. If it is lost, there is no benefit and also far more climate damage than from the immediate or eventual release of CO₂ into the atmosphere.

James Handley says

David,

You may be interested in our earlier post on how to include methane emissions in a carbon tax. See Would a Methane Tax Make Natural Gas a Green-Enough “Bridge” Fuel? (May 20, 2011)