Guest Post by Sieren Ernst, Principal of Ethics & Environment. [See 3/23 post-script, below.]

Whether or not simplicity is a personal virtue, it’s certainly an important advantage of a carbon tax over other forms of carbon pricing. Thus, the “discussion draft” on carbon taxes released last week by a bicameral task force headed by Rep. Henry A. Waxman (D-CA) and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) shows a laudable trend toward simpler, more transparent ways to price carbon pollution. Despite that encouraging trend, some aspects of the draft seem to have steered out of the way to complicate an otherwise elegant concept.

Dozens of peer-reviewed economic papers have examined the key design questions that the Waxman-Whitehouse draft asks: How high should the tax start? What should the escalation rate be? Where to use the revenue? The Waxman-Whitehouse task force offered up a menu of options and asked the public to weigh in, reality-tv style, on their favorites at cutcarbon@mail.house.gov.

It’s axiomatic to microeconomics that larger price signals produce larger responses on both the supply and demand side. One need not consult economic models to know that the impact of a low carbon price and tiny escalation rate — such as the task force’s low-end option of $15 per ton of CO2 with an escalator of 2% per year — would be minuscule. Would you modify your driving behaviors more than slightly over an increase of 15 cents per gallon of gasoline? Clearly, we need the task force’s higher-end option — $35 per ton and 8% escalator — to put a real dent in U.S. CO2 emissions, or at least to top the expected reductions from EPA regulatory proposals.

But the task force didn’t ask for input on a myriad of important design issues that needlessly clutter up the proposal. A major advantage of a carbon tax over cap-and-trade is its simplicity and crystal-clear price signal. An advantage touted by cap-and-trade supporters over a carbon tax is that the pricing mechanism is flexible. The ‘discussion draft’ seems to offer a carbon tax with cap-and-trade characteristics that isn’t especially simple nor flexible.

For starters, the bill uses a confusing and complex upstream/downstream approach, imposing the tax upstream in some instances and downstream in others. The “backgrounder” accompanying Waxman-Whitehouse proposal claims that this is “simpler” and imposes a lower reporting requirement. The background document asserts that “taxing carbon in natural gas at the point of production may be impractical, as there are over 500,000 produce natural gas wells in the United States.” But the number of natural gas wells isn’t the operative figure, insofar as a single corporate entity can control thousands of wells. Even the authors of the backgrounder seem to realize they may have picked an unwieldy point of regulation. They concede, “Applying a tax at the first point of sale would require establishing a new regime, as the federal government does not currently tax the vast majority of natural gas production.” True. Most carbon tax proposals suggest taxing natural gas “midstream” at the pipeline level because there are relatively few pipeline companies and they’re already regulated.

The Waxman-Whitehouse task force suggests that their approach would cover a larger share of the economy. But according to the Congressional Research Service, the Climate Protection Act, an upstream carbon tax proposed last month by Senators Sanders and Boxer, would cover 2,869 facilities and 85% of the greenhouse gas emissions in the economy. According to EPA, the Waxman-Whitehouse discussion draft would cover 7,000 facilities and…85% to 90% of the economy. The EPA and CRS’s methodology may differ but it seems clear enough that imposing the tax upstream would create far less administrative and regulatory burden.

The discussion draft instructs the Department of Treasury to sell polluters permits for each ton of CO2 emitted. But the proposal stresses that permits can’t be banked, borrowed, or traded. So why add the extra machinery for a permit-based system instead of a straight point-of-sale tax?

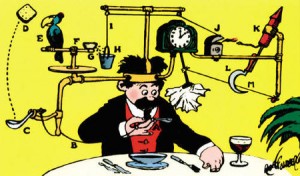

All in all, Waxman and Whitehouse’s proposal looks like an enormous stride, especially when compared to complex, opaque proposals of just a few years ago. But its choice of a permit-based system raises the question of whether their aim is to start with a carbon tax but wind up with linked cap-and-trade systems as Australia and South Africa have announced they will do. Which leads one to ask: Why not continue the trend toward simplicity with a simple, upstream carbon tax with a substantial escalator calibrated to hit long-term emissions targets?

Photo: flickr, Wikipedia: Rube Goldberg machine (“Self-operating napkin”)

Post Script: Coverage of Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gases (3/23/13):

In addition to taxing CO2 pollution, the Waxman-Whitehouse “discussion draft” would tax six non-CO2 greenhouse gases (GHGs): methane, nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, hydrofluorocarbon-23, perfluorinated chemicals and nitrogen triflouride at CO2-equivalent rates. According to the “backgrounder” released with the discussion draft, these non-CO2 GHGs account for about 20% of the climate damage from U.S. GHG emissions. To address that sector, the draft would apply emission fees to facilities whose emissions of those gases exceed the 25,000 ton CO2-equivalent per year threshold in EPA’s GHG reporting rule.

Those emissions total about 263.3 million tons CO2-equiv. That’s substantial: it’s roughly 4% of the 6.7 billion tons CO2-equiv of U.S. GHG emissions in 2011 and helps explain the Waxman-Whitehouse proposal’s reported coverage of 85-90% of emissions; 5% more than the 85% coverage of the Boxer-Sanders proposal that applies only to CO2 emissions.

But it’s striking that the Waxman-Whitehouse proposal would cover only 263.3 million of the 1.1 billion tons of non-CO2 GHG’s in EPA’s inventory. Given the potent climate impacts of non-CO2 greenhouse gases and reports indicating substantial fugitive methane emissions, we recommend a more comprehensive approach, either by applying the tax further upstream (where more of the emissions would be attributable to large emitters above the threshold) or by reducing the 25,000 ton CO-equiv. threshold, or both.

Jack Bradin says

The high end @$35.00 and 8% automatic rise is doable, but not quite enough; $50.00 and 10%>. The gas issue[upstream] @ the pipeline link can work. Here is how: The transmission company collects the price per ton and any escalation % when it occurs. The money is collected there by netting the daily flow and prorating it downstream every 24 hours, that is not the problem. The suppliers will have to pay or no monies for them will be paid by the transmission co.

All carbon taxes must be collected downstream. No Trade of any sort it is a TAX, suck it up or stop breathing.

All subsidies must be repealed as it makes no sense to subsidize what you tax!!!!!!