This post is a response to a set of five questions we received from Paula Swedeen, an ecological economist from Olympia, WA. Paula graciously granted permission to reprint her e-mail; our answers follow each of her five questions.

Hello Mr. Komanoff — I recently downloaded and read through your updated carbon tax model. Thanks for making this publicly available — it’s an extremely useful tool for thinking through how a carbon tax might work and potential optimal designs. I also read the exchange that you and your colleague James Handley had with Dave Roberts at Grist last November-December which laid out some interesting questions about how to spend revenue from a carbon tax. I have a few questions about the policy implications of the results of your default case, and about some of the assumptions in the model.

My background is in ecological economics and biology, and I work quite a bit at the intersection of forests and climate change. I consult for non-profit environmental groups and Tribes on conservation policy for forests and aquatic ecosystems. While I have worked on the portion of California’s climate policy that impacts forests, I am not wedded to using cap-and-trade for addressing climate change, and think a carbon tax has some important advantages at the national level.

Here are my questions.

1) Your default case of starting a tax at $15/ton of CO2 and increasing it by $12.50 a year results in an average rate of emission reductions of 2% per year between 2014 and 2036 (amount of average annual reductions compared to emission levels in 2013, the year before the tax starts). While this results in substantial reductions compared to what we are doing today, much research, as you are no doubt aware, points to the need for global emissions to decline at rates in excess of 5-6% per year, starting now, in order to meet even a 50% chance of staying below a 2 degree C temperature rise (a frighteningly weak goal to start with). From a global equity perspective, the U.S. ought to at least meet that average requirement, if not exceed it given our historical emissions. See for example, Anderson and Bows, 2011 (http://rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/369/1934/20.full.pdf+html).

1) Your default case of starting a tax at $15/ton of CO2 and increasing it by $12.50 a year results in an average rate of emission reductions of 2% per year between 2014 and 2036 (amount of average annual reductions compared to emission levels in 2013, the year before the tax starts). While this results in substantial reductions compared to what we are doing today, much research, as you are no doubt aware, points to the need for global emissions to decline at rates in excess of 5-6% per year, starting now, in order to meet even a 50% chance of staying below a 2 degree C temperature rise (a frighteningly weak goal to start with). From a global equity perspective, the U.S. ought to at least meet that average requirement, if not exceed it given our historical emissions. See for example, Anderson and Bows, 2011 (http://rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/369/1934/20.full.pdf+html).

What other policies, in addition to the already robust carbon tax you propose, do you see as being available to accomplish the other 3-4% annual rate of emission declines we should be achieving?

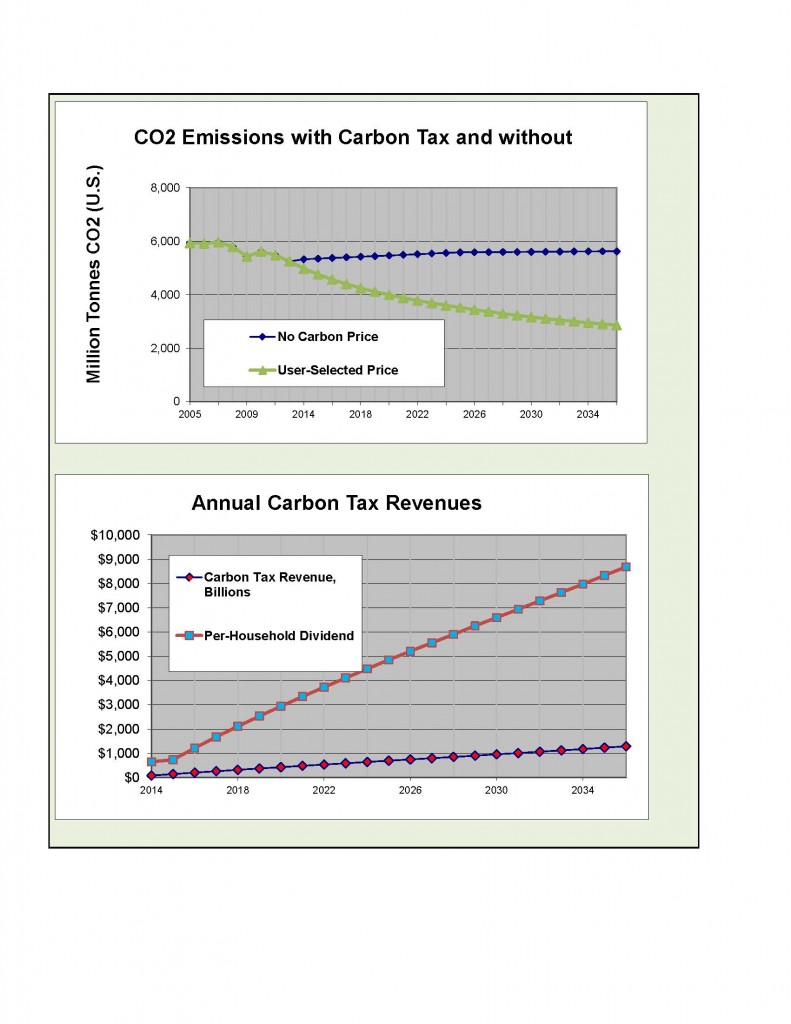

Answer: Our default tax is based on the 2009 Larson bill. I calculate a slightly stronger reduction rate for it than you did: 2.5% a year from 2012 to 2036. (Here I’m comparing projected 2036 emissions of 2,860 million metric tons of CO2 with actual 2012 emissions of 5,243, and of course I’m compounding the average.) But your point stands.

To some extent, that disturbingly small average is an artifact of the diminished “bite” built into any additive tax that increments by a constant annual amount: the tenth $12.50/ton tax increment has less salience to households and industry than the first. At some point, the additive rises would need to give way to constant-percentage-increase rises, unless the rate had already achieved market-clearing levels — a scenario we critiqued in this space several years ago as over-optimistic.

Any model tends to have greater predictive value in the near term than the far, and thus we’re more heartened by the 3.1% average decline rate predicted for the first dozen years than we are discouraged by the 1.9% average rate for the second dozen. But even a 3% annual decline rate is wanting, as you noted.

The ideal carbon tax is, thus, steeper even than Larson’s “aggressive” bill. But we have to begin somewhere. As for complementary policies, we’re impressed with the 100% Wind-Water-Sunlight vision propounded by Stanford professor Mark Z. Jacobson and his team. His new paper in Energy Policy, “Examining the feasibility of converting New York State’s all-purpose energy infrastructure to one using wind, water, and sunlight,” is a good place to start.

2) In your exchange with Dave Roberts, you acknowledge that there are barriers to clean technology deployment, but state that the strength of your tax compared to the proposals coming out of Brookings or MIT would exert more technology pull to overcome these barriers. However, given that this pull looks to result in about half or less of the rate of emission reductions needed, does this influence your perspective on whether spending some of the revenue from a carbon tax on deployment and R&D would be worthwhile?

Answer: We’re all for basic energy research, but less enamored of government-funded development and deployment. In any event, we believe that dedicating “incremental carbon-tax revenue” to transparent and progressive federal tax-shifting or per-household dividends will do more to cut carbon than spending it on RD&D. It will do so by preserving the political bargain that makes possible next year’s carbon-tax increment, and the increment after that, and so on (as evidenced in British Columbia, where 100% revenue return preserved political support for the yearly tax rise), and thus creates powerful price signals that can drive investment, not to mention research and development.

3) The equity argument of needing to refund the tax to consumers, especially low income households, is very important. Using the revenue numbers from your default case, and U.S. Census Bureau numbers for household income distribution, it looks like over $500 billion in dividends would go to households making more than $200,000 a year over the 22 years you modeled out the tax. This is a substantial sum of money going to people that could arguably afford higher energy prices, and whose carbon consumption behavior may not change all that much based on the size of the refund compared to their incomes. What do you think about directing that money to clean energy deployment and other emission reduction efforts instead? I understand the political reasons for giving a refund to everyone. However, are there other technical or economic arguments for not having an upper income cut-off and instead using the revenue for direct emission reduction projects?

I am very interested in your perspective on this point, because it seems that given how late we are in the race to avoid an irreversible threshold to a largely uninhabitable planet, we should be throwing everything we have at the problem. I have a hard time seeing how we can afford to refund such large sums of money to high income households when it could be used to important effect elsewhere. Would it not be worthwhile to vastly expand public transportation, and/or put as many solar arrays on available roof-tops as could be purchased, or keep forests standing rather than recycling revenue to those who likely don’t need it? A $200,000 annual income cut-off for a refund would still shield low and middle income families from energy price increases. Obviously, other income cut-offs could be used, but you get the idea.

I definitely get the idea, and I thank you for the calculation (which I confirmed , probably using the same Census income table as you; it puts 4.2% of U.S. households at or above your cutoff, which I multiplied by the projected $14.8 trillion in cumulative “available” carbon-tax revenue to 2036, to calculate $620 billion.)

My response parallels my answer to Question #2: for me, the value of preserving the structure of the overall arrangement (in which equal per-household dividends of the tax revenue engender public and political support for the tax to keep rising) overrides both my strong personal feelings about economic inequality and my awareness (which I share with you) of the potential payoff from allocating the $620 billion to infrastructure and energy projects that could push down CO2 emissions further. Here I’m particularly concerned with the perceived arbitrariness of an income cutoff. Consider that in just the tenth year of the tax (2023 if it starts in 2014) the per-household dividend will exceed $4,000; in which case a household with an income of $199,000 will make more money, with the dividend, than one with an income of $201,000. Yes, sliding scales could be devised, but these threaten to make the distribution so complex that it becomes vulnerable to other carve-outs which then cascade to a point where it loses its public appeal.

4) Forest loss is a large source of carbon emissions globally. Most of the emissions come from tropical deforestation, but conversion of forests to housing and commercial real estate in the U.S. (and some other management changes) is projected to make domestic forests a net source of emissions by 2030. Allocating a very modest portion of carbon tax revenues to both the U.S. contribution to financing an end to tropical deforestation, and to preventing forest conversion domestically directly reduces CO2 emissions, and has numerous ecological and social co-benefits. Having worked in this particular field for over 20 years, I know that coming by adequate funding for forest conservation is a huge challenge – this is another race we are losing to disastrous consequences. Carbon taxes are being used by other nations, like Norway, to address emissions from tropical deforestation. And Waxman-Markey allocated some auction revenue for forest conservation. Using carbon tax revenue to reduce forest-based emissions, or even increase biological sequestration, also has the advantage of not trading off forest emission reductions for a portion of fossil fuel emission reductions, as occurs under an offset system with cap and trade. I am concerned that if no portion of carbon tax revenue goes to this purpose, there will be few other sources of revenue adequate to the task. Do you have any thoughts on this topic?

Answer: We advocate briskly-rising carbon taxes as a needed corrective to spur low-carbon energy innovation and to encourage renewables and efficiency in a price system that lets them compete fairly. But the same logic that points to the need for a carbon tax to “internalize” the social cost of carbon pollution in fossil fuel prices suggests that payments are needed to assure the continued social benefit of carbon sequestration services by forests and aquatic ecosystems. As you point out, these ecosystems are being diverted to more financially lucrative uses because their climate and other ecological benefits are unpriced. Under “the polluter pays” principle, those who benefit from dumping carbon into the atmosphere should pay for the service of sequestering it safely. And yes, that’s a lot more direct and clear than using offsets under cap-and-trade to fund ecological services.

As noted, we recommend returning carbon tax revenue (either as a tax shift or a direct payment) primarily as a way to mitigate regressive effects and to build the kind of long-term political support we’ve seen for British Columbia’s revenue-neutral carbon tax. But the argument for using at least a portion of the revenue stream to fund carbon sequestration services strikes us as compelling. Several carbon tax proposals suggest allocating funds from harmonizing border tax adjustments (essentially tariffs) on carbon-intensive imports to finance international forestry projects. Under that structure, carbon tax revenue from domestic goods would be “recycled” to households, while the import tariff would fund preservation and restoration of forests and perhaps aquatic ecosystems’ capacity to sequester carbon.

5) Can you briefly describe your confidence in your price elasticity assumptions? I noticed when ramping up the tax in your model, for example to start at $40/ton and increasing it by $20/year, the average rate of emission decline does not respond that dramatically — it goes from 2% up to 2.6% per year. Do you have any sense of the chances that your model might either over or underestimate individual and business reaction to carbon price increases?

Answer: My math yields a somewhat different result. Comparing projected 2036 emissions with actual 2012, and again using compound averages, I calculate a 2.5% annual average decline with the default $15.00/$12.50 tax, and a 3.7% decline rate with “your” $40.00/$20.00. Your tax is roughly two-thirds higher than mine in 2036 and has achieved a roughly one-half greater decline rate, which seems plausible.

Again, though, your broader point is well-taken: the elasticities in the model are merely estimates, not “facts,” and they are particularly uncertain on the supply side, which is the anticipated locus of the decarbonization process under a carbon tax. (In three of the model’s six sectors, a majority of the CO2 reductions come from fuel decarbonization, whereas in only one, air travel, does a majority come from reduced usage; one sector is split 50-50 and reductions in the sixth, natural gas usage in industry and heating, are necessarily all via less usage because natural gas can’t be decarbonized further.)

It does appear that our model is conservative (predicting lower CO2 reductions) than most other models. Perhaps it needs to be more attuned to the extent to which strong, clear price signals will encourage development and deployment of low- and zero-carbon technologies. We hope to explore and explain these differences via further analysis.

Thanks for any time you have to address these questions.

Best,

Paula Swedeen

Thank you for your collegial and thought-provoking questions!

Paula Swedeen says

Charles and James,

Thanks much for your thoughtful answers. You have helped me understand some of the nuances and also to focus my overriding questions a little more. And, the idea on how to use carbon tax revenue for forest conservation is a new one to me, and much appreciated.

I want to drill down on the role of public spending because you seem to dismiss its role almost entirely: Your model defines the limit of the aggregate impact of a carbon tax on the economy. Can complementary policies, without additional government spending, really accomplish the additional 2-3% annual reductions we need?

The new Jacobson paper you refer to still requires some public finance for several of the near-term actions he proposes. He advocates for the expansion of both New York State and federal DOE programs for solar and transportation infrastructure projects. These programs are funded through tax dollars – the public part of public-private partnerships. He also recommends many changes in public policy, which means government in both the regulatory and fiscal dimensions has to work.

I also keep coming back to public transportation as an example: Your model demonstrates that internalizing the cost of carbon pollution only reduces emissions slightly in the personal ground transportation sector. Yet, there are large gaps in adequate availability of even basic bus service all over the country that if filled could significantly reduce the need for individuals to use their cars to get around. Hybrid and full electric bus technologies are available today. Federal DOT grants to the states could start reducing emissions from private ground transport immediately. How do you get additional reductions beyond what carbon tax can do, without public spending? And why not do it when it is so uncomplicated to expand existing types of services with existing technologies? How is this a bad investment of carbon tax revenue?

Obviously, I am left feeling dissatisfied with the answer that government spending has no role when the stakes are so extremely high and it is likely that complementary policies will also require some form of public monies. Remember, I am not talking about an either/or on spending the revenue. My suggestion of an income cut-off gives the vast majority of the money back to consumers. Also, I do not claim that public funding is always spent well on renewable energy or public infrastructure, but given the crisis we face, there is much about government, the private sector, and civil society that will have to improve if we are to avoid massive human suffering.

So, can you please say more about why you have so little confidence in public spending? If it is purely political – i.e., that money needs to go to high-income households in order to pass and maintain the tax, then I think that re-focuses the discussion on how to change the politics. If you think its needed, but should come from other sources, then the discussion can focus on how likely or unlikely it is to re-allocate funds already spoken for in the budget. As you know, the beauty of a carbon tax is that it brings in “new” revenue. It seems to me that it is much more efficient from a policy perspective –i.e., using the fewest number of policy changes to bring about the biggest change as soon as possible, to try to set the precedent early to use some portion of the revenue to accomplish what the tax cannot do by itself.

Cheers.

James Handley says

Hi Paula,

Thanks again for your thoughtful, substantive questions and follow-up. I often find myself urging flexibility about the revenue side of a carbon tax; I save my ardor for our essential point: a substantial and briskly-rising carbon tax can do more (and more quickly and cost-effectively) than any other policy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

British Columbia’s 100% revenue-neutral carbon tax has reduced emissions 17% over the past 5 years, according to a CBC News report posted under Latest News. But we also applaud Tom Friedman who yesterday urged (on NPR’s “To the Point”) that carbon tax revenue be used to fund the social safety net, deficit reduction and clean energy R&D. You (and others) certainly make a compelling case for transit which tends to be underfunded and yes, transportation tends to be a sector that’s less responsive to price signals than others.

Charles is up to his eyeballs in the effort to enact congestion pricing in NY City to fund transit; we’re both avid cyclists, you can be sure transit is close to our hearts.

But I think it’s fair to say that like most economists, we’re skeptical about legislative bodies choosing the most effective ways to reduce CO2 emissions. Clear price signals can take advantage of existing markets to spur low-carbon development and new technologies much better (and usually faster) than subsidies. Within reason, I think we’d support any formula for the revenue side than can work politically to enable enactment of a substantial and briskly-rising carbon tax. We just know so much more specifically what we don’t want (CO2 pollution) than what we do want (hundreds, if not millions of behavior changes) that the revenue side strikes me as secondary. BC’s carbon tax (which incremented every year for four years) seems fair and widely-popular. If 100% revenue return is the key to that broad, sustained support (the carbon tax was proposed by finance minister Carole Taylor in Gordon Campbell’s centrist Liberal Party), we should take notice.

David F Collins says

I would be very leery of funding transportation, healthcare or any such thing with Carbon Tax revenue.

For purposes of discussion, let us suppose that due to the Carbon Tax (and other necessary measures), CO₂ emissions are reduced to a small fraction of present rates, and that Carbon Tax revenues fall accordingly. We would still need transportation, healthcare, etc.

Taxes can serve Pigovian purposes. They also serve as sources of revenue to fund governmental functions.

David F Collins says

I must apologize for not congratulating CTC and Paula Sweeden on a wonderful discussion!

Paula Swedeen says

Hello David,

Your point is well taken. It would not be wise to replace existing funding for health care or transportation or Social Security (which is a danger if a carbon tax is used to replace payroll taxes) when carbon tax revenue should eventually decline. What I am suggesting is not replacing any existing funding sources, but augmenting them. CTC’s model shows both an increasing total amount of revenue for 23 years, and a stubborn inability of the tax to reduce emissions very much from personal ground transportation. Being able to use some portion of this steadily increasing revenue stream to enhance existing shortfalls in public transportation funding for 20 plus years to directly reduce emissions in a difficult sector seems worthwhile to me. Can you say more why you think this would not work? Do you think carbon tax revenue won’t actually increase for that many years? Or that its not a good idea to set something up upon which people depend, but know that at some point in time the revenue source will have to be replaced? Or…? Do you have other ideas for reducing emissions from personal car travel, and other sources of revenue for public transit? Thanks.

David F Collins says

Thank you for your astute questions, Paula!

Absolute flag-nailed-to-the-mast positions tend to be unwise. Circumstances change; futures tend to be a tad difficult to foresee. I tend to think that divvying up Carbon Taxes and returning them to citizens on a count-the-noses basis is the wisest; the surety of rising taxes, like hanging in the morning, are among the things that concentrate the mind. I can spend my CT bonus on solar heating, insulation, PV systems etc. for my home; none of us are all grasshopper, we are all ant, too, at least in part. Let a thousand flowers bloom and all that.

Nevertheless, your point on transportation is a good one. we cannot shorten all the distances we must travel. Where I work and where my wife works. On that enchanted evening when I met my lovely stranger across a crowded room, I gave no thought to the compatibilities of our future commutes; other thoughts were foremost in my mind. The Calories-Я-Us, Computers-Я-Us etc. are where they are and not necessarily situated for our convenience, even though we live in NE Chicago. There is need for massive investment in public transportation which is energy efficient. On a somewhat related note, intercity passenger travel by rail in these parts is of maybe Third World quality; what is needed is not a Maglev or Bullet Train or TGV but something maybe as good as what Grandpa Collins used back in the Gay 90’s when he took a break from his studies and traveled from Champaign to Davenport to court Grandma. But that all by itself could use up a lot of CT revenue. And once the investment has been made, operation, maintenance and development requirements should not need CT funding.

Repurposing, reinventing and redesigning the whole economy should be motivated by but not funded by Carbon Taxes.

I studied engineering and languages, not economics. I cannot justify my thoughts by other than hand-waving. Please be merciful.

David F Collins says

Paula: I have changed my mind: I can no longer support returning all CT revenues to the People on a strict count-the-noses (i.e. pro rata) basis. The complexity of reality hit me hard, after a recent after-church conversation with the Rev. Tom Raab, who recently retired from running our help-the-local-needy program (in NE Chicago). Tom has many decades of experience with the situation of the «financially challenged».

Specifically, he pointed out that folks in dire financial straits find little priority in applying funds toward reducing future expenses: their current needs take priority. They would be likelier to buy gas-guzzler cars that could reliably get them to work, rather than an economical car; they would take better housing (he well knows what living in substandard housing is) over moving closer to work. They are the most likely to be taken in by con artists than other people.

Unsurprisingly, Tom is not favorably inclined toward the Carbon Tax. Indeed, he is not ready to consider esoteric (to him) issues like Global Warming or Resource Depletion. But he did convince me that a certain amount of dirigiste paternalism is called for. Specifically, investment in public transport, land use, energy conservation, agro-reform, and the like.

Nick says

Hi Charles,

Your response to Paula’s 5th question notes that your price elasticities were estimates and involved notable uncertainty; I am curious if you can point to any sources that informed these estimates? Thanks

Richard Ottinger says

Dear Charles:

As you know, I am a big fan and long time collaborator of yours, and I also convinced that a refundable carbon tax is the best approach to tackling climate change.

But I agree with Paula that having a cut-off on refunds makes sense, not only from an equity viewpoint but from a carbon reduction point as well. Most of the super wealthy aren’t going to use their rebate funds for solar panels. They probably will use them for larger gas-guzzling yachts and private planes. And they and their conservative Congressional pawns aren’t going to support a carbon tax anyway. They derrive a lot of their wealth from exploitation of fossil fuels and cutting down forests. Their interest is in preventing any action likely to kill the goose that layed their golden eggs. So I would advocate having a reasonable refund cut-off and return more of the refund to the lower and middle income folks who have seen their job and educational opportunities, incomes, wealth and security dwindle seriously for the last couple of decades.

But if the choice is between refunds for all or no carbon tax, I’ll take the former. Alleviating climate change is a matter of survival of the planet and its human and other populations and environment. It simply must be addressed.

All the best. Dick Ottinger

Richard L. Ottinger

Dean Emeritus

Pace Law School

Former Member of Congress

Richard Ottinger says

Dear Charles:

As you know, I am a big fan and long time collaborator of yours, and I also am convinced that a refundable carbon tax is the best approach to tackling climate change.

But I agree with Paula that having a cut-off on refunds makes sense, not only from an equity viewpoint but from a carbon reduction point as well. Most of the super wealthy aren’t going to use their rebate funds for solar panels. They probably will use them for larger gas-guzzling yachts and private planes. And they and their conservative Congressional pawns aren’t going to support a carbon tax anyway. They derrive a lot of their wealth from exploitation of fossil fuels and cutting down forests. Their interest is in preventing any action likely to kill the goose that layed their golden eggs. So I would advocate having a reasonable refund cut-off and return more of the refund to the lower and middle income folks who have seen their job and educational opportunities, incomes, wealth and security dwindle seriously for the last couple of decades.

But if the choice is between refunds for all or no carbon tax, I’ll take the former. Alleviating climate change is a matter of survival of the planet and its human and other populations and environment. It simply must be addressed.

All the best. Dick Ottinger

Richard L. Ottinger

Dean Emeritus

Pace Law School

Former Member of Congress