Post hoc, ergo propter hoc

I took Latin in high school, and I loved unraveling classic phrases like After this, therefore because of this ― a common logical fallacy that attributes event B to event A because A preceded B.

Okay, so that’s not quite what Politico and the New York Times did this week when they linked the sharp drop in power plant emissions in the Northeast U.S. from 2005 to 2012 (“B”) with the regional CO2 trading system known as RGGI (“A”). But they came pretty close:

Politico: Nine Northeastern states already take part in a regional trading network that puts an economic price on their power plants’ carbon output . . . The Northeastern states saw their power plants’ carbon emissions drop more than 40 percent from 2005 to 2012, the trading network told EPA in December — without any of cap-and-trade critics’ apocalyptic expectations for such a system.

The Times: The regional program [RGGI] has proved fairly effective: Between 2005-12, according to program officials, power-plant pollution in the northeastern states it covered dropped 40 percent.

That’s linkage, all right. But does it matter? Well, on Monday the Obama administration is set to issue regulations spurring creation of state cap-and-trade programs intended to reduce CO2 emissions from coal-fired power plants by up to 20 percent — “the strongest action ever taken by an American president to tackle climate change . . . [with] far more impact on the environment than the Keystone pipeline” (!), according to the Times. And, the Times reports, the plan is built on RGGI:

Officials with the northeastern regional cap-and-trade program . . . have played a significant role in shaping the new rule. In frequent trips to Washington over the last several months they have consulted with [EPA Administrator Gina] McCarthy and other top E.P.A. officials.

How strong a foundation, then, is RGGI for a national program that, to quote the Times once more, “could become one of the defining elements of Mr. Obama’s legacy”? Let’s see.

To start, the 40 percent drop cited in both Politico and the Times appears to check out. The RGGI folks have a fantastic Web portal, and it enabled me to look up annual CO2 emissions from every fossil-fuel generator in New York, my home state. The 2012 statewide total, 35.4 million tons, was 43-44% less than 2005 emissions of 62.7 million tons. That’s impressive.

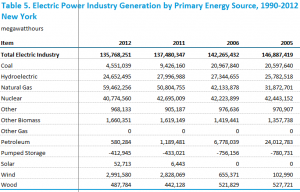

To peel back how that reduction came about, I downloaded Energy Information Administration state electricity data for New York [Table 5], which is collected in the graphic above (with 2007-2010 excised to fit the page). You can see at a glance that oil fell out of the electricity sector, giving up 23 million megawatt-hours from 2005 to 2012; that coal dropped nearly 80%, shrinking by 16 million MWh; and that the majority of the combined 39 million MWh decline, more than 27 million MWh, was picked up by natural gas. Sure, wind added a little, and efficiency helped more (as reflected in the decline in total MWh), but basically it was gas (with attendant methane leakage) that delivered the coup de grace to higher-CO2-emitting oil and coal generation in New York State.

So was it RGGI that nudged New York State electricity generation to gas from oil and coal? That hardly seems possible; the price for RGGI carbon-emission permits has been so anemic that any shove by RGGI must have been pretty limp.

The price has fluctuated over time, of course, as shown in a graphic compiled by analyst Adam Cohen at the Pace Energy and Climate Center at Pace Law School. Most of the time, the price to emit a ton of CO2 appears to have ranged from just under $2.00 to a little over $3.00. That jibes with a program average of around $2.50 per ton that I calculated, using RGGI data, by dividing cumulative permit proceeds of $1,662 million by total CO2 allowances sold of 675 million tons.

Which takes us to our final question: how much would an average $2.50/tonCO2 permit price motivate generators to switch from coal to gas? (I ignore petroleum, the “middle” carbon polluter among the three fossil fuels, for simplicity.) My answer is: not much. Comparing a conventional (10,000 Btu/kWh) coal plant to a state-of-the-art combined cycle gas-fired power plant (6,000 Btu/kWh), I calculate that a $2.50/ton carbon price confers a comparative advantage on the gas-fired plant of just 0.15-0.20 cents/kWh. (See calculation at end.)

Less than a fifth of a cent per kilowatt-hour is peanuts in the wholesale market, in which fuel costs for fossil-based kWh’s range between 2 and 4 cents, and in which O&M costs, dispatchability and plant modernization expenses (driven in part by compliance requirements for “traditional” SO2, NOx and particulate pollution) also affect the fuel mix. It’s hard to see how a 0.20 cent a kWh or less burden on coal (and less than that on oil) relative to gas would have driven the sea-change in the power mix shown in the table — which gave rise to the roughly 40 percent drop in utility-sector CO2 emissions in New York State and, by extension, in the eight other RGGI states.

This isn’t to say that a higher permit price might not have done more. And perhaps the anticipation of robust permit prices (that never materialized) influenced supplier decisions early on. And, yes, RGGI revenues have financed demand-side programs that contributed to the reduction in electricity usage shown in the table and, thus, the decline in CO2. But crediting RGGI for more than a modest piece of a 40 percent overall decline is a huge stretch.

Who knows, perhaps the administration will surprise us and its Monday announcement will offer states a carbon tax option ― like British Columbia’s, which since 2008 has delivered a transparent and effective price signal ― in addition to the cap-and-trade option. If we thought that was in the cards, we wouldn’t be gnashing our teeth over this latest round of RGGI/cap-and-trade hype. But we’re not holding our breath.

Calculations: a conventional (10,000 Btu/kWh) coal plant emits 2.1 lb of CO2 per kWh, while a state-of-the-art combined cycle gas-fired power plant (6,000 Btu/kWh) emits 0.7 lb, for a difference of 1.4 lb per kWh. A CO2 price of $2.50 per ton, or 1/8 of a cent per pound of CO2, thus imparts a difference of one-eighth of 1.4 cents per kWh, i.e., 0.18 cents/kWh.

Jonathan Koomey says

What I think is going on is that the anticipation of other environmental regulations is pushing the Northeast utilities to move out of coal. Those plants are old and dirty, and they are pretty expensive to operate. They also have high externality costs. The move away from oil is quite dramatic, and I hope someone looks into the causes for that, but most plants that burn oil can easily switch to natural gas, and back again, so this may be a reversible phenomenon that has been pushed by low gas prices. Someone with more detailed knowledge of the Northeast utility markets can probably comment more specifically.

Russell Lowes says

Concurrent with what you are saying, there are two EPA attorneys that put out a video several years ago that claim that the NE cap & trade mechanism did not drive the reduction in acid rains. This video was done before the majority of the switch from coal to gas.

They said that the acid rain component of pollution was accomplished by switching coal sources from dirty NE coal to cleaner (still dirty) Montana or Wyoming coal. They say that simple regulatory pressure, not cap & trade, caused this cleanup of the acid rain problems. I wonder what has happened to their case (protected by PEER for whistle-blowing).

Mark Seaman says

Re Russell Lowes’ comment:

I think you’re referring to the sulfur dioxide (SO2) cap & trade program, implemented by the US in 1995. There is debate as to how much of the reduction in SO2 was due to the cap & trade program versus earlier deregulation of the railroads, that allowed for cheaper transportation of low-sulfur coal from Montana and Wyoming. But it seems likely that the cap & trade program did drive some portion of the reductions and was better than a class command-and-control approach.

See http://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/rstavins/Papers/Schmalensee_&_Stavins_SO2_Paper_JEP.pdf