Today’s welcome announcement of a surprise U.S.-China agreement to curb greenhouse gas emissions almost certainly commits the United States to a national carbon price. Non-pricing measures, such as the EPA Clean Power Plan to cut power plant emissions and the ramp-up of auto fuel economy standards now underway, won’t be nearly enough by themselves to meet the new U.S. target of 25% lower emissions by 2025 vis-a-vis a 2005 baseline, according to calculations by the Carbon Tax Center.

This could be terrific news for carbon tax proponents, since it would finally require climate-concerned organizations and officials to put carbon pricing — preferably in the form of a revenue-neutral carbon tax — at the heart of their climate agenda. On the other hand, given the new Congressional ascendancy of the climate-deaf Republican Party, the 25% target could prove to be just another climate goal scuttled by U.S. political resistance.

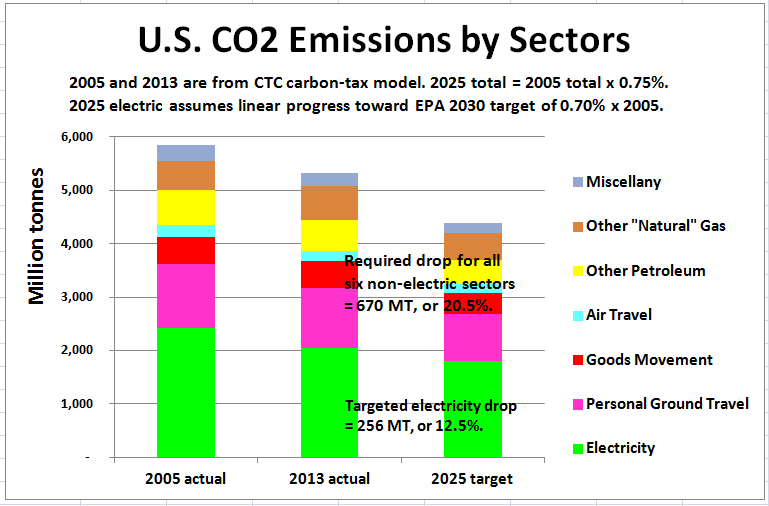

Let’s start with the carbon emission numbers, which we’ve broken down between emissions from electricity generation, which account for around 40% of U.S. CO2 pollution, and emissions from the various “non-electric” sectors like automobiles, goods movement, air travel, industry and heating, which account for the other 60%. This division is useful for at least two reasons: there’s much greater maneuverability in electricity due to the relative ease of substituting clean sources like solar and wind for dirty coal and gas, and the U.S. already has an emissions goal for the electricity sector: the 30% reduction by 2030 (from 2005) embodied in the Clean Power Plan announced by President Obama this past June.

The key numbers are shown in the graphic. A 2025 target equaling 75% of actual 2005 CO2 emissions of 5,855 million tonnes (metric tons) from all U.S. sources equates to 4,391 million tonnes. With that figure established, let’s switch our reference frame to current (2013) emissions, which were 5,317 million tonnes. (All figures are from CTC’s carbon tax model, and some may differ from recently released official U.S. emission figures, but only slightly.)

The difference between 2013 emissions (5,317 million tonnes) and 2025-targeted emissions (4,391 million tonnes) is 926 million tonnes. That’s a 17.4% drop over just a dozen years. The questions are: where in the U.S. economy will these reductions take place, and how will they come about?

This is where the electric/non-electric split is useful. The EPA Clean Power Plan targets a 363 million-tonne reduction in electric-sector emissions from 2013 to 2030. (Click here for the math.) That averages to annual reductions of 21-22 million tonnes per year. Applying that pace to the 12-year interval from 2013 to 2025 implies an electric-sector drop of 256 million tonnes. Considering that the total 2013-2025 reduction has to be 926 million tonnes, that leaves 670 million tonnes in reductions for the non-electric sectors.

That’s a strikingly ambitious target — at least in relative terms. On a percentage basis from 2013, non-electric emissions would have to drop by 20.5%, whereas electric emissions must drop only 12.5%. This is a stark reversal of the prevailing view (which we at CTC share) that the electricity sector continues to have more low-hanging fruit because of the relative ease of replacing high-carbon supplies with low-carbon sources.

To be sure, there’s no intrinsic reason the electricity sector couldn’t surpass the EPA target and thus take at least some of the pressure off the other sectors. Indeed, with solar-cell prices continuing to fall and PV technology and finance finally mainstreaming, optimism is rampant about the capacity of renewables to displace coal- and eventually gas-fired generation. Still, solar’s share of U.S. electricity supply is so small — it reached an average of 0.4% for the first half of this year (wind power’s share also reached a milestone, 5%) — that the ramp-up would need to be nearly miraculous to surpass the EPA power-sector reduction target of 30% for 2005-2030 without a boost from carbon-emissions pricing.

The other caveat to our calculations is that the U.S. commitment appears to be for “greenhouse gases” and thus may allow methane and other GHG’s to assume some of the percentage load we’re numerically assigning to CO2 alone. On the other hand, some reports are saying that the U.S. commitment is to a 26% or even 28% overall reduction, which would probably require 25% cuts in the CO2 component.

Our inference, then, is that the U.S.-China agreement actually commits the United States to do something unprecedented: to cut non-electricity emissions of carbon dioxide so substantially that a carbon-emissions price will have to be part of the underlying policy package. After all, in the eight years from 2005 to 2013 — a period marked by little (just 10.4%) GDP growth — those emissions fell just 5.1%; but now, over the next twelve years, non-electric emissions will have to fall by 20.5%, or four times as much.

The ongoing phase-in of higher auto mileage via stronger CAFE standards can only be a part of that, given that automobiles (including “light trucks”) account for just a third of those non-electric-sector emissions (see graphic). The lion’s share of the accelerated reductions will therefore have to come about not via regulatory mandates alone but through economy-wide shifts permeating American society and involving less driving, fewer freight-miles, greater re-use, higher efficiencies in buildings, machinery and appliances, and even the emergence of a national conservation ethic.

That’s a lovely vision, and a tall order. In our view, there’s no way it can happen without a national carbon price — delivered via a transparent and relatively tamper-proof tax on CO2 emissions.

Richard Kev says

Considering the shear numbers of humans on this planet, it seems we should be taxing food by its carbon content, not just fossil fuel. After all, we burn food chemically, consume O2 and emit CO2. If a tax on carbon consumption through the use of fossil fuels would have a positive effect on climate change, then a food/carbon tax makes perfect sense. And, a tax of this kind, to be fair, must be distributed equally. A gluttonous American who weighs 300 pounds would be paying substantially more in food/carbon tax than would a poor Asian peasant who weighs only 100 pounds. But to omit poor people from the tax would mean that their CO2 emissions don’t contribute to the CO2 problem. All contribute. All pay. Sure, an overweight individual would pay more because he consumes more, but to omit the 1.4 billion people who live in China, or the 1.3 billion in India, or the 1.1 billion who live in Africa, would mean you think the personal CO2 emissions of over half the world population don’t affect climate change, whilst only the CO2 emissions of North America and Europe are the culprits. We need to institute a Personal Carbon Emissions Tax now, if we are to save the planet.

John Robertson says

Last year (2013), globally, human activity presented 35.9 Billion tons of CO2 to the atmosphere, of which 18 Billion tons actually made it to the atmosphere, the balance having been absorbed by the ocean, forests and other ecosystems. This is impressive until one realizes that the atmosphere weighs in at 5.5 Million Trillion tons. Therefore, CO2 contribution to the atmosphere by human activity is a staggering 0.000327%. Frankly I was shocked that 3.27 Ten Thousandths of One Percent could be noticed let alone be incorporated into a General Climate Super Computer Model.