(co-authored with CTC senior policy analyst James Handley)

Sheldon Whitehouse gained renown last year for his series of weekly “Time To Wake Up” speeches on the Senate floor addressing the climate crisis. Today, the Democratic Senator from Rhode Island took his climate leadership further as he introduced a comprehensive bill intended to end free dumping of climate pollution into the atmosphere. (Click here for video of the senator’s 80th speech, introducing his bill.)

Whitehouse calls his 30-page measure, which is co-sponsored by Democratic Senator Brian Schatz of Hawaii, the “American Opportunity Carbon Fee Act.” It builds squarely on the growing consensus that clean energy will rapidly and fully displace fossil fuels only when polluters are made to pay for causing climate damage. AOCFA would impose fees on both CO2 and non-CO2 greenhouse gases including fugitive methane from shale gas wells and coal mines. AOCFA also includes a border tax adjustment to impose equivalent climate pollution fees on imported goods from nations that have not enacted their own climate pollution fees. (Click here for background on border tax adjustments.)

AOCFA pegs its pollution fee to U.S. EPA’s estimate of the “social cost of carbon.” The fee would start at EPA’s current estimate of that cost, now $42 for each ton of carbon dioxide, and would rise by 2% annually in real terms. Emissions of methane and other greenhouse gases would be charged in proportion to their estimated per-unit global warming impacts relative to carbon dioxide.

The Senator’s office estimates that AOCFA would raise $2 trillion in revenue in its first ten years, money that would fund an “American Opportunity Trust Fund” to be returned to the American people in as many as nine different ways including tax cuts, dividends, infrastructure investments and debt relief. E&E News reporter Jean Chemnick wrote today that the bill “leaves open the question of how those revenues would be spent as an invitation for would-be Republican collaborators to negotiate.”

Sen. Whitehouse’s decision to link his bill’s climate pollution fees to the social cost of carbon could be problematic, however. Published estimates of the social cost of carbon vary from as little as $10 per equivalent ton of CO2 to over $300, depending on what is counted as climate damage, what discount rate is assumed to convert future losses to present terms, and how heavily if at all catastrophic risk scenarios are factored in. And while hitching the pollution fee to the EPA social-cost estimate may resonate with some stakeholders, it could limit the level of the carbon tax and, thus, its ability to drive down U.S. emissions rapidly enough, let alone global emissions.

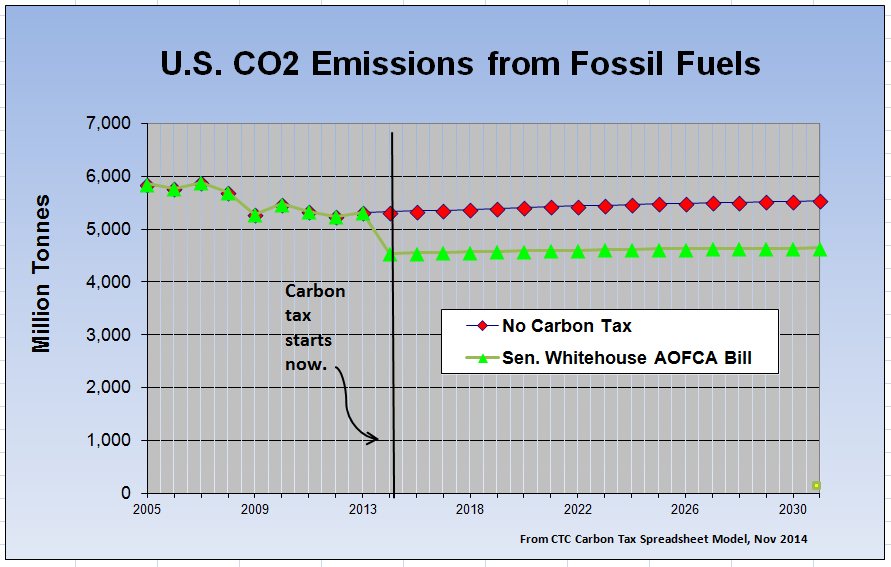

After a rapid drop due to the bill’s aggressive starting price, emissions would stabilize instead of declining further, on account of the low price trajectory.

Indeed, we ran the Whitehouse bill through the Carbon Tax Center’s 7-sector price-elasticity spreadsheet model and found both good news and bad. The proposed starting price of $42 per ton of CO2 would quickly reduce US emissions by about 15%. (Though our graph shows the full drop occurring immediately, the decline would actually materialize over several years due to lags in behavioral and equipment changes.) But the bill’s subsequent 2% annual real price increases would serve only to offset the rising emission tide due to increased affluence, resulting in essentially flat emissions rather than a declining curve.

Furthermore, economists Frank Ackerman and Elizabeth Stanton argue that the social cost of carbon isn’t an appropriate framework for assessing climate policy or setting a carbon price. In an unusually thoughtful paper surveying the literature on the topic, they recommended setting the carbon price on the basis of the trajectory needed to reduce emissions fast enough to avoid catastrophic warming.

The other key design feature in the AOCFA carbon tax — its initial step from zero all the way to $42 per ton of CO2 — is also concerning. That price equates to around 40 cents per gallon of gasoline and as much as 4 cents per kWh of electricity for a 100% coal-dependent utility (or around half that for a U.S. average). Overnight increases of these magnitudes are beyond the capacity of many households and businesses to absorb overnight. A more modest starting price combined with a steeper upward slope, such as the trajectory embodied in the Managed Carbon Price Act introduced in May by Rep. Jim McDermott (D-WA), would nudge emissions downward year after year while giving individuals and businesses years rather than months to adjust to higher fossil fuel prices.

Notwithstanding these reservations, the Carbon Tax Center applauds Sen. Whitehouse’s proposal for its boldness, completeness and transparency. The timing is also noteworthy, with the bill introduced as Senate leadership shifts to the Republicans and the prospects for broader tax reform may be improving. While any carbon tax is obviously a long shot at best in the next Congress, implementing a tax on climate pollution while offering the possibility of reducing taxes on productive activity may be the only way to thread the political needle over the next two years.

Appendix: The Whitehouse bill, by the numbers

Readers may want to see how AOCFA might stack up against the Obama Administration’s proposal announced in June to use EPA rulemaking to reduce CO2 emissions from the electricity sector in 2030 by 30% from the 2005 level.

By our calculations, presented graphically here, the Obama proposal requires 2030 emissions from electricity generation to be no greater than 1,690 million metric tons (“tonnes”). We estimate that Sen. Whitehouse’s bill would bring 2030 power plant emissions down to 1,516 million tonnes — around 25% less than 2013 emissions, and 37% less than “baseline” 2005 emissions. While that decrease would surpass the Obama target by 174 million tonnes, it’s questionable whether that “promise” would induce supporters of the EPA rule, including the major mainstream environmental organizations, to accept a deal in which the EPA approach is swapped out for the carbon tax.

Outside the electricity sector, AOCFA’s emissions trajectory looks less impressive. U.S. emissions from non-electricity activities (driving, freight movement, air travel, non-electric heating and industrial process, oil refining, etc.) totaled an estimated 3,264 million tonnes in 2013. (You can see a breakout by sector in the graph on our home page.) By our modeling, this figure would fall only slightly, to 3,124 million tonnes — a 4% drop from 2013 — under the AOCFA carbon price trajectory.

The difference between the robust predicted decline in electricity emissions and the small drop in non-electricity emissions is largely rooted in the lack of readily available low- or zero-carbon fuel alternatives outside of the electricity sector. Structural and behavioral changes such as more-efficient buildings, reining in sprawl, and de-emphasizing distant travel and goods movement will need to play a major role in decarbonizing those sectors — a transformation that will almost certainly require a more robust carbon-price ramp-up than that provided by the Whitehouse bill.

David Collins says

For starters, I am glad that the AOCFA has been introduced and is getting some (albeit not much) attention. I am unbothered by its weaknesses: addressing these and debating them brings more attention, which is good. Unfortunately, one reason the AOCFA’s weaknesses are no problem is that the bill’s chances of passage are in the zone between negligible and none.

James Handley says

David,

Senator Whitehouse has astutely left the revenue side of his bill open — if tax reform starts to gain momentum, its $2 trillion in cumulative revenue (over a decade) should help make the proposal salient.

Adelaide says

Do you want to copy articles from other blogs rewrite them

in seconds and post on your page or use for contextual backlinks?

You can save a lot of writing work, just search

in gogle:

rheumale’s rewriter