Editor’s note: Yesterday the world’s most influential newspaper finally did what CTC and other carbon tax proponents have sought for years: publish a ringing endorsement of a U.S. carbon tax. With its editorial, The Case for a Carbon Tax, the New York Times joins the growing community of opinion leaders, policy experts and, yes, elected officials who not only recognize the power of carbon taxes to quickly and equitably reduce emissions but also sense the emergence of a political critical mass that can enact fees into law. This heartening development signals that it’s not too soon to focus on the design of a U.S. carbon tax, especially its magnitude and rate of increase, as CTC senior policy analyst James Handley does in this post.

Which is the more effective way to set a tax on carbon pollution?

A. Start aggressively, then raise the rate slowly (“sprint”).

B. Start modestly, then raise the rate briskly and predictably (“marathon”).

You probably guessed that if the goal is to instill incentives that will bring about big emission reductions fast enough to avoid runaway global warming, the answer is B, the marathon. Yet a leading U.S. Senate advocate of legislative action on climate seems to be starting off like a sprinter, perhaps because his legislation is pegged to estimates of the Social Cost of Carbon that don’t account for the possibility that climate change will turn out to be catastrophically costly.

More on that senator in a moment — after this tutorial:

The Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) is a construct to quantify in monetary terms the damage caused by each additional ton of CO2 added to the atmosphere. While the SCC may sound arcane or academic, estimating its magnitude has real world implications: governments are pegging climate-related regulatory decisions to SCC estimates. A low SCC can make all but the lowest-cost clean-energy policies pencil out as expensive; higher estimates justify more rapid and aggressive measures, since moving too slowly to reduce emissions shows up as a mistake whose costs accumulate at a frightening pace.

Calculating the damage from a ton of CO2 turns on a host of assumptions that span wide ranges. Not surprisingly, estimates of the SCC reported in the peer-reviewed economics literature range from as little as $10 per ton of CO2 to over $400. A profoundly important modeling choice is how heavily to weigh the risks of climate-induced catastrophes. High-risk climate scenarios with nearly infinite costs, such as rapid release of methane from arctic permafrost or sudden sliding of vast ice masses into the ocean, “misbehave” in the equations used for conventional cost-benefit analysis, leading some modelers to omit them altogether.

One widely-used model assumes that economic growth rates will not be affected by climate change, thereby predicting that half of the world’s economic activity would continue after a whopping 18 degrees C of global warming. Other models dilute the high-risk scenarios by assigning them arbitrarily low probabilities that suppress their impact when their costs are averaged in with low-risk scenarios. A further problem in estimating the SCC is the bias toward high “discount rates” that telescope future impacts down to seemingly manageable proportions.

Amidst fraught debate and widely-divergent estimates, the Interagency Working Group has settled on $42 per ton of CO2 as the “official” U.S. government social cost of carbon. While that’s an improvement over past practice that omitted climate costs entirely — tacitly, an SCC equal to zero — the $42 figure grossly understates the large-scale global risks that dominate concern over global warming and climate change.

And even if there were a “perfectly” specified SCC that accounted for catastrophic risks, it would still make for a problematic framework for setting a carbon tax. Indeed, there are practical, real-world reasons for the carbon tax to start below the SCC — to allow households and businesses at least a little time to adjust to higher fossil fuel costs — but to soon rise to meet or even exceed the SCC, in order to counterbalance institutional barriers that prevent societies from responding to price signals fully and instantly.

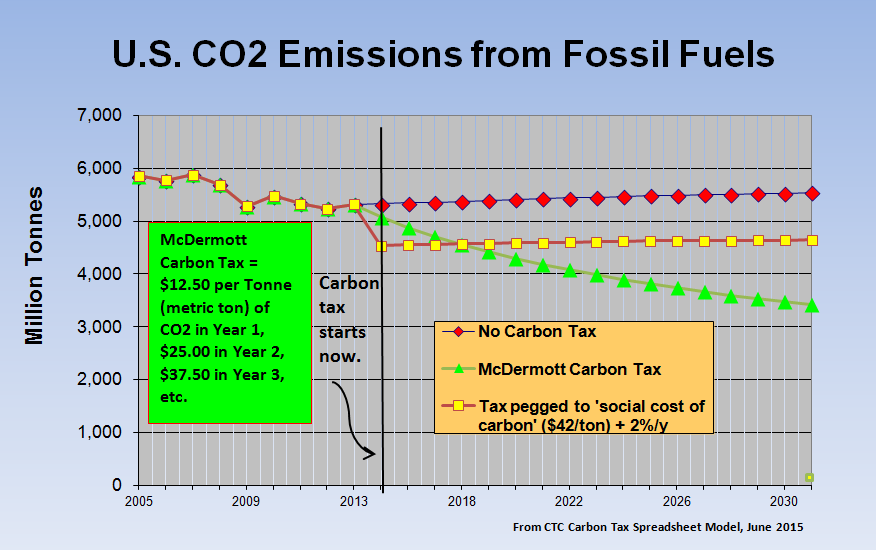

A U.S. carbon tax should thus not be tethered to the IWG’s “central” SCC estimate. Instead, it should set a price and upward trajectory that can slash domestic emissions and serve as a template for other countries — as does Rep. Jim McDermott’s “Managed Carbon Price Act.” Starting at $12.50 per metric ton of CO2 (equivalent to $11.34 per U.S. ton), the McDermott carbon tax would rise by that same amount each year to reach triple digits before the decade is out — a trajectory that would drive down U.S. emissions by about one third in that time, according to CTC’s carbon tax model. And if global climate negotiators shift from squabbling over emissions caps to a price-based negotiation, as Harvard economist Martin Weitzman urges, a similar global price trajectory would slow emissions fast enough to offer a decent shot at avoiding runaway warming.

Which takes us to Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI). This Wednesday (June 10), Sen. Whitehouse is to present his proposal for an economy-wide tax on greenhouse gases, the American Opportunity Carbon Fee Act (AOCFA), to the American Enterprise Institute. When Senator Whitehouse unveiled his bill last November, we applauded its broad coverage of all major greenhouse gases and its WTO-oriented border tax adjustment provisions. Presenting the proposal at AEI, a leading GOP and business-oriented think-tank, is a smart play for bipartisan support. The Senator’s willingness to discuss an array of options for use of the carbon tax revenue is a helpful invitation to his colleagues of both parties to fold carbon taxes into broader tax and regulatory reform.

But we would be remiss if we did not examine the bill’s effectiveness at reducing catastrophic climate risks. AOCFA’s pollution fee is pegged to U.S. EPA’s estimate of the SCC. The price would thus begin relatively high, at $42 per ton of carbon dioxide, but then rise by just 2% annually in real (after-inflation) terms. In our estimation, this trajectory could be the worst of both worlds.

On the one hand, the overnight step from a zero carbon price all the way to $42 will hit hard. A $42 price per ton of CO2 equates to more than 4 cents per kWh for a 100% coal-dependent electric utility. In states like West Virginia, Kentucky and Missouri, where retail electricity prices average just 8₵/kWh (and industries and buildings are organized around cheap power), rates would rise more than 50 percent overnight. Without time to find and install low-carbon substitutes as well as more efficient processes and products, a sudden increase of this magnitude would be received as a punishment rather than a low-carbon incentive. The political pushback would be immense.

Moreover, we fear that without a persistent upward price trend, the climate benefits of AOCFA’s relatively high initial price will peter out. Our carbon tax spreadsheet model predicts that after an initial rapid 15% drop due to the bill’s aggressive starting price, CO2 emissions would rise on account of increased affluence and the rise in energy demand that tends to accompany it in the absence of continuing price incentives.

We’re feeling a bit of cognitive dissonance. We’re encouraged that Senator Whitehouse — in many ways the Senate’s outspoken climate “conscience” – is championing a simple, explicit carbon tax as the key policy to avert climate catastrophe. But while we admire his proposal’s elegant overall architecture, we’re concerned that the aspect of a carbon tax that matters most — its scale — is oddly miscalibrated.

Matt Weldon says

I appreciate a forum for policy discussion and your points above. These are the topical areas we should be discussing: the several philosophical foundations we may choose to secure carbon pricing, who gets the money and how we determine the price.

I prefer to base the fee on a foundation of property ownership. Any owner of property should be compensated for its use as a disposal reservoir. As the air and ocean are in the public domain, everyone should get a cut. We only set the price of emissions at zero now out of tradition, not for a profound philisophical reason. It was presumed unnecessary and/or deemed impractical to assess a price. Now we know that it is necessary. We also clearly have the technological means to assess a meaningful market price and distribute revenue broadly.

Having swiftly dealt with the first two topics, I’ll add the observation that pricing as far upstream as possible (well head, mine, import facility) in our economy and distributing revenue to household consumers will leverage all market participants. Diverting any money to specific mid-stream market sectors (renewable energy for example – though a fan, we should eliminate all such direct subsidies) ignores that the majority of a consumer’s carbon footprint is embedded in the products they buy. We must deliver any carbon fee revenue to the rightful owners not only to protect them from financial harm but to also realize the maximum benefit, both economically and in carbon emission reduction.

Sending revenue to household also minimizes concerns regarding any step price impact. This can be done efficiently and most households (as many as 2/3rds) will actually be net beneficiaries from a well founded carbon fee structure because carbon emissions do correlate to household wealth. The vulnerable populations you noted will be OK if the revenue is distributed broadly to reservoir owners.

Back to the third topic – what is the best price profile? I completely agree with your statements regarding this issue being a “marathon”, that “predictability” is a requirement and that catostrophic scenarios shouldn’t be discounted to the point that they are ignored. The ultimate price should be tied to performance. The fee can continue to rise until our emission performance begins to reflect the needed progress. One can even imagine a time in the future when the fee will begin to decrease to some low price as atmospheric carbon dioxide levels return to a value believed to be sustainable (say 300 ppm?).

Only substantial emission prices have the potential to address the worst case scenarios, because only when the market is enabled to value carbon sequestration will that activity grow to the needed scale. With a predictable carbon price in place, whose ultimate price is based on performance, the economy will create a market sector that successfully moves pollution emissions from public property (air and ocean) to private property (land) where all the participants are consciously, actively, and willingly engaged.

It is ironic that some self-annointed paragons of the private market fight pricing of an economic by-product when it is the act of pricing that will ultimately allow sustainable market structures to grow and flourish. Not just to protect our environment and ourselves now, but to justify long term investments in the fossil fuel industry so that we may continue to enjoy the unique capabilities and products it delivers.

with kind regards,

Matt

Rick Knight says

Fully agree with Matt Weldon’s points, and well-said.

Rick Knight says

For some additional context on the sensitivity of the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) to a host of assumptions – some economic, some scientific – please read the following paper by Moyer et al. It highlights how, ill-advised as it is to peg a carbon tax to the SCC, it’s even worse than that because of the huge uncertainties in the validity of assumptions that seem not to be adequately questioned https://geosci.uchicago.edu/~glotter/research/papers/Moyer_JLS_2014.pdf

David F Collins says

Regarding two Global Warming scenarios, “Rising Discomfort” and “Catastrophe”, I would opine that the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) has some meaning in the former and none whatsoever in the latter. I would further opine that the probability of the latter is high enough to render action plans based on the former to be irresponsible, not worthy of consideration.

The SCC is the cost of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere once the global climate has stabilized to the steady (not growing) concentration of these gases. As long as the concentration continues to grow, the SCC is meaningless in the absence of a strict limit.

My “opinion” resulting from these views is that the best Carbon Tax is the one that most effectively reduces greenhouse gas releases and eliminates them the soonest. That is what Mr Handley refers to as the “marathon”.

And yes, we must applaud Senator Whitehouse for his efforts. How can we get thru to him regarding these points?

Rick Knight says

Another great point! The SCC only has meaning as an instantaneous value. As soon as it’s calculated, it’s obsolete.

Susan Eisendrath says

While James and Matt are right on target and illuminate the issues related to the value of running the “marathon” rather than “sprint,” unless Senator Whitehouse has overwhelming support for a $42 price per ton of CO2, which I doubt he does, it seems like a good strategy to let him bargain high and hard to push for that price and let those who oppose a high price “win” a lower price, since that’s what we think will establish a more effective long term carbon tax.

James Handley says

Hi Susan,

While Senator Whitehouse’s $42 is a big jump, the far more important number — his 2% annual ramp-up — isn’t “bargaining high.” Quite the opposite. It’s so minuscule and sharply out of line with Sen. W’s impassioned warnings about the perils of global warming from the Senate floor that I have to wonder if it’s just a terrible mistake!

Dick Smith says

James Hadley’s takeaway is important. Don’t legislate based on the social cost of carbon. It’s a nice theoretical concept, but modeling produces such a wide range of outcomes (depending on one’s assumptions) that it’s useless in the real world.

As CTC explains elsewhere, there are four basic estimation flaws in the economic models that “low-ball” the SCC.

(1) climate sensitivity estimates ignore higher estimates;

(2) damage estimates at low-temp increases (2.5C) are off;

(3) damage estimates at high-temp increases (10C to 20C) are just silly. As James Hadley pointed out here, a DICE model that assumes we’d only lose half our global GDP with an 18C temp increase;

(4) discount rates are too high.

Mr. Hadley He also nails another takeaway–we need political support for the carbon price–particularly as the price increases to the levels we need to get emission reductions (e.g., $100/ton in less than 10 years with the McDermott bill).

However, he ignores the only way to maintain political support for the kind of aggressive price increases. We need to rebate most of the carbon-tax revenue we collect from fossil-fuel companies to American consumers. We need to protect low-income and most middle-income Americans from rising energy prices. That is the only way to maintain support for the aggressive tax increases that are necessary to achieve the kind of reductions we need (like the one’s James properly praised in the McDermott bill that get us over $100/ton within 10 years).

As Mark Twain said, the difference between the right word and almost the right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug. That’s the difference between a carbon tax and carbon tax that is revenue neutral. Only a carbon tax that I revenue neutral can garner the necessary political support.

David F Collins says

Mr Smith: Your plea for making the Carbon Tax politically palatable is on target. And making it refundable to the people is favored by economist right and left. It seems self-evident.

But there are reasonable arguments against the 100% refunded Carbon Tax. This surprised me!

Ideally, people would use a good portion their Carbon Tax payback to prepare for a lower-carbon short-term future and a zero-carbon long-term future. Insulate their houses. Buy solar panels, high-mileage cars. Live closer to work; work closer to home. And so forth. Meanwhile, the rich and the foolish would subsidize the poor and the prudent.

I have learned of the problems with this from some social workers, charity do-gooders and others at church. When people of limited financial resources run into expensive surprises (a kid needs extensive dental work; a close relative loses a job; home or car repairs become necessary; there are more such unwelcome surprises than you can dream of), long-term prudence becomes an imprudent luxury. Predictably, a clear majority of these fellow parishioners oppose a Carbon Tax, preferring Big Government command-and-control approaches. (Good Lord, grant me patience, charitability and, please, a silver tongue!)

My parents, both of whom enjoyed financially comfortable childhoods, learned during the Great Depression that poverty is expensive.

Provision must be made for helping the unfortunate. Using a portion of Carbon Tax revenues to fund such a bureaucracy can be proposed as one alternative. (I am sure all of us can devise other and better alternatives, but so what.)

Rick Knight says

One of the misunderstandings about the revenue rebate or dividend given to households is that it must be used to install solar panels. This is not true. In fact, one of the beauties of this policy is that it does NOT compel anyone to use the money in any specific way. But the price of fossil fuels and fossil-intensive goods continues to rise, and consumers quite predictably spend less money on goods and services when their prices rise. That is #1. The second effect of the revenue rebate/dividend is that it immediately creates demand throughout the economy for low-greenhouse-gas options, ideas, and products, encouraging investors to put their money into enterprises that produce them. That completely changes investment decisions by utilities and other businesses, so that even if individual consumers don’t make big life-changing choices like solar panels. It could be as simple as buying more chicken instead of beef, or choosing a different electricity provider when the choice is offered, or deciding that car-pooling is not such an annoyance after all. With 300 million people being nudged to make more climate-friendly choices, the cumulative impact would be enormous.

James Handley says

We’ve discussed revenue distribution in The Carbon Tax Revenue Menu. And here: Investing/Recycling the revenues. We consider three general options: Tax Shifting, Dividends, as well as Investing In Alternatives. Each of them has some merit and it’s the kind of compromise that political institutions are set up to make. For example, British Columbia’s popular and effective carbon tax returns revenue by cutting taxes on wages and income and by distributing revenue directly to low-income households.

This post focuses on a different question: How to set the tax rate and trajectory over time to achieve climate objectives. The Carbon Tax Center seems to occupy a unique niche — we’re pointing out the benefits of a pollution tax that starts modestly but keeps rising to continue reducing emissions for decades. That’s different than a price that hits once and then basically stops — after an ambitious start at $45/Ton CO2, Senator Whitehouse’s proposal would rise only 2%/yr (roughly $1).

While the debate about price trajectory is probably a long way from real political salience, we feel it’s important to point out now that a carbon tax isn’t a quick fix. It’s a long term policy that has to continually signal throughout the economy that we want less fossil fuel pollution and more renewable energy and efficiency, as Rick described above. The race to de-carbonize our economy is a marathon — and only a briskly-rising carbon tax will set the pace for the long run to reduce the risk of catastrophe.