Steven Cohen, executive director of Columbia University’s prestigious Earth Institute, recently weighed in on the carbon-tax debate in the Huffington Post. The results are breathtaking – and not in a good way.

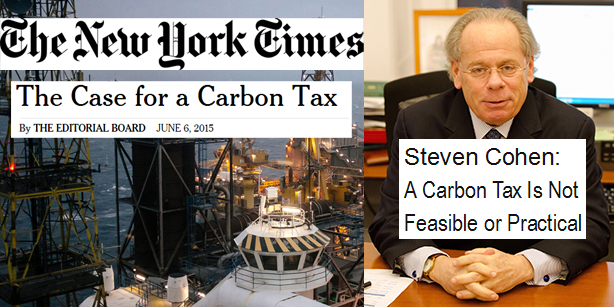

Cohen’s June 8 screed, “A Carbon Tax Is Not Feasible or Practical,” was a riposte to a New York Times editorial two days earlier endorsing a carbon tax as “one of the best policies available” to address global warming. The Times is wrong, says Cohen, as he proceeds to lay out a multi-count indictment. Among his anti-CT arguments are the following:

1. Carbon taxes are politically infeasible: Given the system’s deep hostility to tax hikes, “the space between the carbon tax as a policy idea and the reality of American politics is too vast to overcome. For better or worse, here in America we are in a period of tax policy paralysis that is unlikely to be surmounted anytime soon.”

2. Carbon taxes are unfair: They “cause people on the lower end of the economic ladder to pay a higher portion of their income on energy,” while corrective measures aimed at redistributing the costs “are far from simple to implement, might stigmatize recipients, and would become easy and obvious political targets.”

3. Contrary to The Times, carbon taxes are unequal to the problem of climate change because they would founder on the shoals of international politics: “China and India would need to go along, and given the urgency of their energy and development needs, it is difficult to imagine that they would agree to such a measure.”

4. Carbon taxes are anti-urban: “I sometimes think the push for a carbon tax comes out of an early 20th century environmentalist mindset that scolds people for consumption and living in evil, immoral cities.”

5. Finally, carbon taxes are unnecessary since tax breaks can be just as easily used to encourage alternative energy development: “Why waste time and effort on an infeasible policy that will never happen? Why not devote time and effort to building a real partnership between the public and private sector to create a sustainable economy?”

Careful readers will notice that the first two items are variations on a theme, which is to say the futility of relying on the U.S. political system to pass a well-crafted carbon-tax plan that discourages fossil fuels without burdening workers and the poor. The same can be said for number three, which is about the inability of a beggar-thy-neighbor international system to institute significant reform. Whether the fault lies with Washington, Beijing, or New Delhi, Cohen argues, the point remains that politicians of all nationalities are too selfish and shortsighted to deal intelligently with a carbon tax, so it’s best to forget the whole thing.

Careful readers will notice that the first two items are variations on a theme, which is to say the futility of relying on the U.S. political system to pass a well-crafted carbon-tax plan that discourages fossil fuels without burdening workers and the poor. The same can be said for number three, which is about the inability of a beggar-thy-neighbor international system to institute significant reform. Whether the fault lies with Washington, Beijing, or New Delhi, Cohen argues, the point remains that politicians of all nationalities are too selfish and shortsighted to deal intelligently with a carbon tax, so it’s best to forget the whole thing.

Charges four and five are different, so let’s tackle those first.

Cohen argues that alternative-energy tax breaks “work as well as tax increases and they have the benefit of being politically attractive,” so why not go with an idea that is more popular? Maybe so – but nowhere does Cohen offer any data to back up his claim that one approach is as good as the other. In fact, when the Carbon Tax Center in January 2014 analyzed a Senate Finance Committee proposal to replace some 42 federal energy tax subsidies with tax credits for “clean (low-carbon) electricity” or “clean fuels,” it found that while such a reform would shave 400 million metric tons off yearly U.S. CO2 emissions by the year 2024, a carbon tax set at the same dollar level would reduce it by 960 million metric tons.[1] That’s nearly two and a half times as much bang for the buck.

So the idea that all fossil-fuel tax schemes are created equal is untrue. A carbon-tax “stick” would work far better than a carrots-only approach based solely on tax subsidies (although the best approach, of course, would be to use both).

As for the claim that carbon taxes are inherently anti-urban, it’s even more fallacious. Roughly thirty percent of U.S. fossil fuels goes to cars and trucks. Under-pricing gasoline, which is what happens when government fails to “internalize” global warming and other such costs via a fuels tax, leads to over-driving, which leads to traffic congestion and suburban sprawl. If Americans spend approximately 40 percent more time behind the wheel than they did in 1980,[2] it’s not because they want to but because U.S. tax and spending policies gave them no alternative. The land of the free and the home of the brave is less free as a consequence.

But pricing fossil fuels more accurately relative to their total social and environmental cost does the opposite. It provides Americans with better information with which to maximize the benefits of motor-vehicle use. Cars and trucks would not disappear if carbon taxes were instituted, but the U.S. would see a pronounced shift to more energy-efficient forms of transport, not only trains, trolleys, and buses, but cycling and walking. In terms of spatial living arrangements, the upshot would be much the same, i.e. a shift from sprawl to high-density cities in which many goods and services are just a short stroll away.

Cohen thus has it backwards. Rather than anti-urban, carbon taxes are pro. In a classic study in the 1980s, a pair of globe-trotting Australian academics named Peter Newman and Jeffrey Kenworthy compared gasoline usage in various world cities and found that per-capita consumption in Manhattan was eighty percent lower than in New York State as a whole.[3] It’s sometimes said that Manhattanites have ninety percent of what they need within a ten-block radius – and if it’s not there, then why bother? So except for the occasional taxi, they get around on their own two feet or on bikes, buses, and subways, but only infrequently by private car.

Carbon taxes would encourage such trends by rendering high-density urban living more cost-effective. The effect is a population shift to walk-able, bike-able cities served by state-of-the-art mass transit – cities crowded with people rather than cars.

Finally, with regard to the question of political infeasibility, let us concede that Steven Cohen has a point, even if the implication is not what he thinks. U.S. government is indeed a mess. Gridlock is the norm, corruption is rampant, and the intellectual tenor of political debate has rarely been lower. In a flagrant violation of one person one vote, immense political power is vested in a Senate that gives Wyoming (population 564,000) the same clout as traffic-bound, multi-racial California (population 37.3 million). Clearly, America’s eighteenth-century Constitution is due for an overhaul, yet the Article V amending clause, which says that any change must be approved by two-thirds of each house plus three-fourths of the states, permits just thirteen states representing as little as 4.4 percent of the population to block any modification sought by the remaining 95.6.

Change is necessary, yet change is impossible. So Cohen is right – the chances of a well-designed carbon tax emerging unscathed from the congressional meat grinder are nil.

But the chances of a well-designed alternative-energy tax-subsidy program emerging unscathed are also nil. Congressmen love targeted subsidies because they allow them to create tax breaks for their favorite constituents and campaign donors. Lobbyists love them, too, because they provide opportunities to wheel and deal on behalf of wealthy clients. But the result is to render any such program that makes it through the system more vulnerable rather than less. In fact, one can imagine The Wall Street Journal’s editorial writers rubbing their hands with glee as they prepare to attack the latest hare-brained liberal giveaway scheme larded with favors for well-placed special interests.

The House kills the bad bills and the Senate kills the good – or so they say. But the beauty of a carbon tax lies in both its economic simplicity and its political difficulty. It is a supremely rational approach that puts the system to the test. It is an instrument not only for environmental change, but for political change as well. Faced not only with global warming but with sprawl, congestion, inner-city decay, and an increasingly dangerous situation in the Middle East – the last the result of a fossil-fuels economy that places immense wealth in the hands of benighted oil sheiks – Americans should demand rational solutions to the problems that afflict them. If the political system is not equal to the task, then they should “ordain and establish” one that is. Rejecting a carbon tax on the grounds that it is too rational couldn’t be more absurd. Steven Cohen should think again.

Daniel Lazare is a writer living in New York City; his books include The Frozen Republic, The Velvet Coup, and America’s Undeclared War.

[1] “Design of Economic Instruments for Reducing U.S. Carbon Emissions,” Carbon Tax Center, Jan. 31, 2014, available at https://www.carbontax.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/CTC_Design_of_Economic_Instruments_for_Reducing_U.S._Carbon_Emissions.pdf.

[2] Vehicle miles traveled in the U.S. doubled over a little more than three decades, going from 1,.5 trillion in 1980 to 3.0 trillion in 2013. See U.S. Office of Highway Policy Information, Annual Vehicle Miles of Travel, 1980-2013, available at http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2013/vm202.cfm. Population, according to the U.S. Census, meanwhile rose by just forty percent. Dividing the VMT growth factor of 2.0 by the population growth factor of 1.4 yields the 1.4 factor (i.e., 40%) in text.

[3] Peter W.G. Newman & Jeffrey R. Kenworthy, Cities and Automobile Dependence: A Sourcebook (Aldershot, U.K.: Gower, 1989), p. 159.

Steve Valk says

Thanks for this post. Tweeting it this afternoon and pinging Jeff Sachs in the tweet. Can’t believe he agrees with or signed off on Cohen’s horrible piece. Anyone who wants to RT, check out the @citizensclimate feed at 2:30.

Rachael Sotos says

I appreciate your post, Dan. You are on target reminding readers that all fossil fuel tax schemes are not created equal; that carbon taxes are not inherently anti-urban. Regarding the question of the alleged infeasibility of carbon taxes it seems to me that Cohen’s piece is neither cogent nor coherent. Perhaps the “political” problem in his thinking is to be found in his quite vague subjective reflection: “I sometimes think the push for a carbon tax comes out of an early 20th century environmentalist mindset that scolds people for consumption and living in evil, immoral cities.” Perhaps there is more than a fallacious claim of anti-urbanism here. Could it be that what is at issue is Cohen’s implicitly techno-utopian world view, intent to solve environmental problems through the rational planning of sustainability managers? (So much may be surmised from the text of his 2011 Sustainability Management advertised in the bio concluding his Huffpost piece).

His claim that carbon taxes are the product of the imagination of anti-capitalist Deep Greens is historically confused at best. In his confused piece he argues that carbon tax advocates would send us all back to the farm, are uninterested in culture, education and the amenities of urban lifestyles. According to Cohen, those who will ensure these greened goods of civilization for us are the sustainability managers who will rationally manage industrial ecology, when liberated from “the dominance of economics in modern policy analysis.” Yes, Cohen is correct regarding the hostility in GOP circles regarding taxes, but things can change (even quickly). Cohen should “think again,” as you rightly put it, Dan. Carbon taxes are not opposed to the work of sustainability managers and all those doing “the real work that will transform the energy base of the world economy.” Carbon taxes are what will most efficiently make alternative energy sources cheaper and will provide the framework in which such serious labor can have meaningful purchase in the world.