The acclaim that greeted China’s pledge in November 2014 to cap its carbon emissions by 2030 was broad yet hesitant. The promise by the world’s Number One emitter to halt the explosive growth in its climate pollution was momentous. But deferring the ceiling to 2030 meant emissions could continue climbing for 16 years, perhaps doubling, on top of the tripling recorded during 2000-2013.

We at CTC chose to see the glass as half-full, and wrote at the time:

Though China’s emissions can still grow in the intervening decade-and-a-half, its cap pledge virtually ensured that its rate of emissions growth would begin bending downward before 2030, on account of the lead time needed to overcome the “inertia” built into the factors that collectively determine emission levels. Moreover, the commitment from Beijing conferred instant legitimacy on political forces within China favoring clean energy and seeking relief from relentless air pollution that kills an estimated 1.6 million Chinese a year.

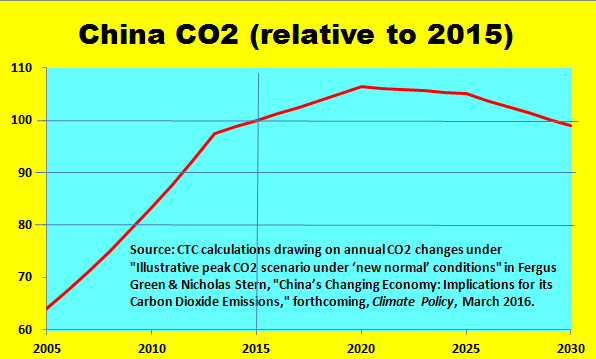

Our optimism has now been amplified, in spades. An analysis released this week, soon to be published in Climate Policy, forecasts that China’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion may peak as early as 2020 — a full decade before the cap target year. Moreover, rather than shooting past earlier benchmarks, emissions in 2030 would be 7 percent below the 2020 peak and even 1 percent under last year’s emissions, according to the forecast. Such a turnaround would exceed all but the most buoyant expectations that greeted the 2014 announcement and would raise the bar for the U.S. and the other 190 nations that submitted emission pledges at the U.N. climate summit in Paris in December.

China’s 2030 CO2 emissions would be 7% less than 2015, under the Green-Stern “illustrative scenario.”

This upbeat analysis comes from two of the world’s most prestigious climate think tanks: the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, both based in London. The authors are Fergus Green, a climate policy consultant from the London School of Economics; and Sir Nicholas Stern, director of the Grantham Institute and arguably the world’s most renowned climate economist.

The premise of the Green-Stern paper is evident in its title: “China’s Changing Economy: Implications for its Carbon Dioxide Emissions.” China’s economy is undergoing a pronounced transition, say the authors, and the implications for energy use and carbon emissions are profound:

The period 2000-2013, it is now clear, was a distinct and exceptional phase in China’s developmental history, during which the very high levels of greenhouse gases emitted were linked closely with the energy-intensive, heavy industry-based growth model pursued at that time. China is currently undergoing another major structural transformation — towards a new development model focused on achieving better quality growth that is more sustainable and inclusive.

During that 2000-2013 period, China’s primary energy consumption grew at a compound annual rate of more than 8% a year. In 2014, in contrast, primary energy consumption grew from 2013 by just 2.2%, and last year’s year-on-year increase through September was less than 1%. The “new development model,” which the authors date from the start of 2014, entails a marked decline in heavy industry’s share of GDP, with output of steel and cement, production of which is extraordinarily energy-intensive, actually falling in the first half of last year.

“These structural changes,” assert the authors, “are occurring on top of ongoing energy conservation initiatives within industry and other sectors [leading to] strong declines in the energy intensity of GDP over the last two years . . . at the same time as GDP growth slowed significantly.” Concurrently, non-fossil electric generation capacity underwent a veritable explosion, from 257 gigawatts in 2010 to 444 GW in 2014.

The motive forces behind this upsurge ― the air pollution crisis, the problematic rise in fuel imports, and the government’s prioritization of zero-carbon power sources as loci of innovation in global markets ― seem certain to endure. Meanwhile, industrial consumption of coal, which Green and Stern say accounts for half of China’s coal usage, appears to be falling as well, not just because steel and cement output are dropping but because production processes are finally becoming more efficient.

Another factor pointing to lower economic and energy growth going forward, say Green and Stern, is “China’s excess capacity in construction and heavy manufacturing.” In effect, part of the past huge growth in fuel use and emissions was an artifact of stockpiling industrial capacity that no longer needs to be expanded, they suggest. Moreover, they assert, “The structural nature of the turnaround in these industries is now widely recognized throughout the Chinese government and the industries themselves. Accordingly, the prospects for declining investment, rationalization and falling production across such sectors in the context of China’s new development model now appear strong.”

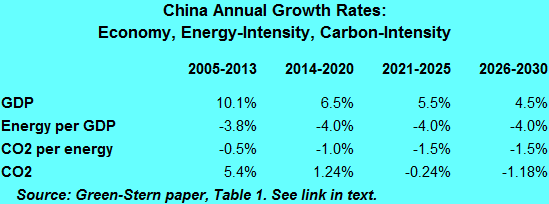

Figures in table underlie historical and forecast CO2 in graph, above.

The upshot is two-fold: first, a lesser rate of GDP growth going forward; second, a continuation of recent declines in the energy intensity of GDP. According to the authors, the primary energy required to produce a unit of economic output fell by nearly 4 percent a year during 2005-2013, and they believe this decline rate can continue indefinitely. They also point to China’s 2020 targets of as much as 300 GW of wind capacity and 150 GW of solar (the latter revised last fall from 100 GW), along with lesser but still sizeable amounts of new nuclear capacity. Even coal-fired power generation is ripe for greater efficiencies, say Green and Stern, as older and less-efficient plants are replaced by newer ones able to wring more kWh’s from the same Btu’s.

Needless to say, maintaining and extending these positive trends won’t be painless, especially in light of ongoing expansions of coal-fired capacity — “despite already enormous amounts of excess capacity” — that have pushed utilization rates for coal-fired power plants below 50%. The authors identify three policy imperatives:

- Rein in expansion of new coal infrastructure in electricity and industry;

- Institute “green dispatch” that prioritizes non-fossil generation over fossil generation, and more efficient fossil generators over less efficient ones;

- “Increase effective carbon prices on fossil fuel energy sources, especially coal.” “Effective carbon pricing,” write Green and Stern, “would alter the economics on the supply-side in ways that would disadvantage high-carbon generators and support green dispatch. A rising coal tax would be a highly efficient and administratively effective measure, well-suited to China’s institutional context, though a well-designed and implemented emissions trading scheme operating in the electricity sector could in theory achieve similar results.”

Green and Stern see CO2 emissions peaking “at some point between 2014 and 2025, depending on how the above factors play out.” A table in their paper (summarized above) presents recent-historical (2005-2013) growth rates for GDP, the energy intensity of GDP, and the CO2 content of each unit of primary energy; and possible future growth rates for each for three future periods: 2014-2020, 2021-2025, and 2026-2030. Resulting future CO2 growth rates are then:

- 1.24% per year for the current period;

- negative 0.24%/year for 2021-2025, owing to assumed 1% slower GDP growth and a 0.5% per year acceleration in the decarbonization of energy;

- negative 1.18%/year for 2025-2030, due to a further assumed 1% per year drop in GDP growth.

Emissions would be massively less than near-universal expectations from just 18 months ago. Yet China can and must do even better. The third Green-Stern policy recommendation, to “increase effective carbon prices,” is key. With robust carbon pricing in place, even the optimistic new scenario from Messrs. Green and Stern could soon come to be regarded as conservative.

david dunn says

We in the west have done little in structural reform especially of the fiscal and economic models we base our economies on , any reduction in carbon emissions has been largely due to the banking and financial collapse in 2008 but all the subsequent efforts to raise both GDP and consumer spending , together with QE has resulted in no slowdown in our economies whatsoever.

It is China who probably lead the way forward as they realise the huge damage of pollution especially is having on their economy and the transition to cleaner city living is moving forward at a pace , whereas in the west we are stuck mainly in the present and not moving forward to replenish housing stock .

We are running fast out of options to make a big difference and quickly enough to be able to make any real difference in the near future unless we tackle the economic and financial aspect of the equation which could be done very rapidly , but the longer left , the more chance of social unrest.