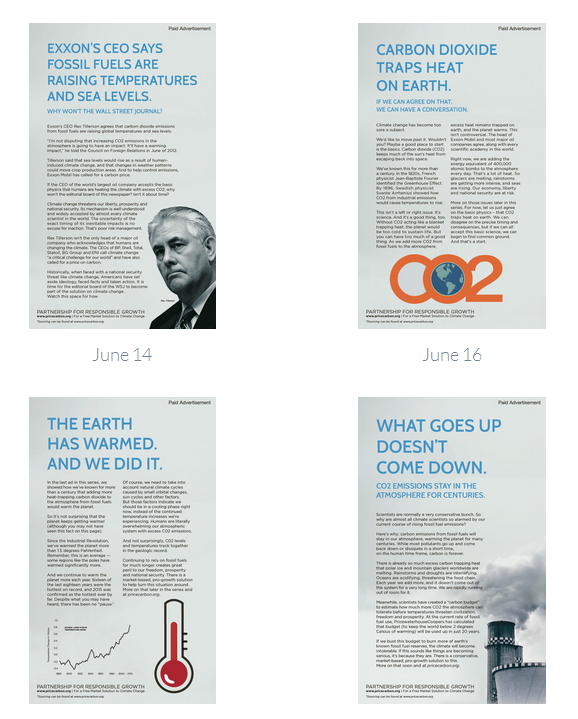

The curtain is up on a series of pro-climate action ads in that climate-denialist stronghold, the Wall Street Journal editorial page. Four ads are up, with eight more to follow by mid-July, produced and paid for by the center-right advocacy group, Partnership for Responsible Growth.

A good deal of craft has gone into the ads, along with a bundle of money — that space doesn’t come cheap. It’s fair to ask what the payoff might be.

Four ads are up, eight are coming soon. Click the link in the top line of this post to read them without squinting.

Presumably, the objective is to help induce a critical mass of G.O.P. Congressmembers to support meaningful carbon-pricing legislation, before it’s too late. A president alone can’t implement economy-wide carbon pricing, and barring a broad leftward upheaval in November, at least one chamber in the next Congress will still be Republican.

Getting a few dozen Republicans to break ranks and support a carbon tax would overcome the House Republican bias baked into the electoral math. A bipartisan bill would also give cover to Democratic Senators and Reps from coal states and exurban counties — there are still some left — whose votes would be needed as well.

Of course, that’s been the situation since the G.O.P. took the House in 2010. Cynics who pronounced carbon taxing dead under a Republican Congress have been proven right — thus far. Yet some facts are changing, and not just in the air, with global-average temperature records breaking monthly. Solar and wind electricity in the U.S. now generate more than twice the electricity, jobs and dollars they produced half-a-dozen years ago, with much of that in red states. A low-carbon or even zero-carbon world can’t be written off as a pipe dream.

Those are political facts. Interestingly, three of the four Journal ads thus far are limited to scientific ones: “Carbon Dioxide Traps Heat On Earth,” proclaims Ad #2. “The Earth Has Warmed And We Did It,” says #3, followed by #4, “What Goes Up Doesn’t Come Down.”

True, the emphasis will change if, as we hope, the series builds to a call for a briskly rising (and revenue-neutral) carbon tax. If so, the initial ads will have been conversation-starters. That would be fine, ordinarily. But while we were taking notice of the ads, the July Harper’s arrived, with a provocative essay by the activist-writer Rebecca Solnit that makes one ask if the series ventured off on a good foot.

Solnit’s essay, The Ideology of Isolation, is an unflinching critique of extreme right-wing thought. It begins:

If you boil the strange soup of contemporary right-wing ideology down to a sort of bouillon cube, you find the idea that things are not connected to other things, that people are not connected to other people, and that they are all better off unconnected. The core values are individual freedom and individual responsibility: yourself for yourself on your own.

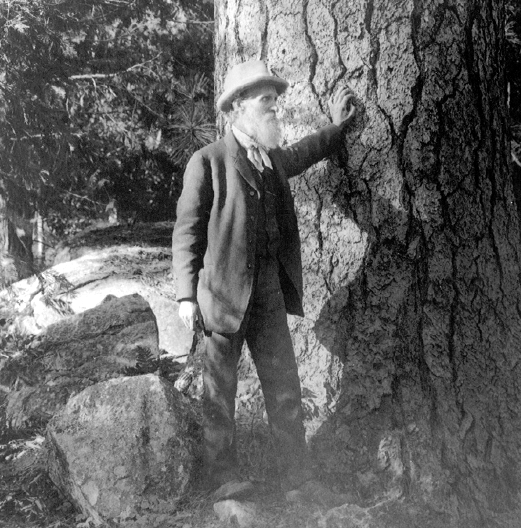

Any student of ecology, or anyone with a passing acquaintance with John Muir, the 19th century explorer-mountaineer-naturalist who founded the Sierra Club, can see where Solnit is going: the ideology that insists we’re not connected to each other, save for a contingent series of market interactions, is the same ideology that denies the interconnections that make up ecosystems and indeed the physical world.

Muir’s glittering aphorism, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe,” demands we pay attention not just to flora and fauna but to the megatons of heat-trapping gases we’ve been sending skyward since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. In contrast, the right-wing ideology of disconnection doesn’t just give us license to ignore our effluent, it practically requires that we do so. Solnit again:

On a more fundamental level, the very idea of climate change is offensive to isolationists, because it tells us more powerfully and urgently than anything ever has that everything is connected, that nothing exists in isolation. What comes out of your tailpipe or your smokestack or your leaky fracking site contributes to the changing mix of the atmosphere, where carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases cause the earth to retain more of the heat that comes from the sun, which doesn’t just result in what we used to call global warming, but will lead to climate chaos.

The central meme in ad #2, that the greenhouse effect “isn’t a left or a right issue, it’s science,” may be sweetly reasonable, but the reader has to believe in science in the first place. As Solnit notes,

If you begin by denying social and ecological systems, then you end in denying the reality of facts, which are after all part of a network of systematic relationships between language, physical reality, and the record, regulated by the rules of evidence, truth, grammar, word meaning, and so forth. You deny the relationship between cause and effect, evidence and conclusion, or rather you imagine both as products on the free market, which one can produce and consume according to one’s preferences.

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.”

And if those preferences are for the riches and influence that come from owning and exploiting fossil fuels, the resulting facts and science won’t lead ineluctably to the position that climate change is real, occurring and principally man-made. In that scenario, the Partnership’s carefully crafted ads may simply bounce off Journal readers and fall harmlessly to the ground.

To be sure, a campaign as professional as the Partnership’s Journal ads isn’t necessarily seeking to change minds through education. The mere fact of the ads — the idea that Republican backers and lawmakers are being addressed on climate from the center-right — is at least as likely to move the political needle as the logical thread in the text.

All the same, there’s another scenario kicking inside the Beltway — we heard talk of it in DC this month — that suggests that a healthy if not House-regaining shellacking by the Democrats will compel the G.O.P. to finally divest itself of its anti-science brand; and that accepting the reality of climate change and a “Republican solution” in the form of a carbon tax could be part of that reformation.

That scenario might have pointed to a more overtly political approach, though that may be where the Partnership’s series is headed. Meanwhile, the initial set may be viewed here. What do you think?