The U.S. power sector is racing past the Clean Power Plan’s emissions target. It’s time for climate advocates to do the same.

Too many climate advocates seem to be investing the Clean Power Plan — the Obama Administration’s project to achieve a 32 percent shrinkage of U.S. electricity-sector carbon emissions from 2005 to 2030 — with iconic significance.

We can understand why: power generation from fossil fuels, primarily coal, was responsible for almost 42 percent of total U.S. CO2 emissions in 2005, more than double the share of the next sector, passenger cars.

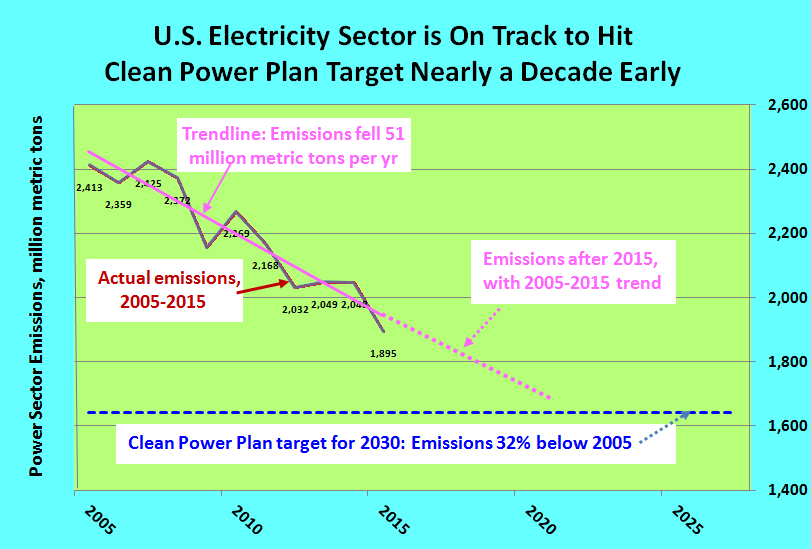

And we at the Carbon Tax Center will grant that the administrative machinery set in motion by the Clean Power Plan may have accelerated the shift in power generation from coal to natural gas and, secondarily, wind and solar, although that shift was already in high gear before the plan was unveiled two years ago (see chart), driven by cheap and abundant fracked gas and the ongoing renewable-tech revolution.

Real climate action requires a much tougher target.

But the CPP target — a 772 million metric ton drop in annual emissions from electricity generation by 2030 — is already in sight, nearly a decade ahead of schedule. Since 2005, the plan’s baseline year, electricity emissions have fallen (as of 2015) by 518 million tonnes. Ten years in, and with 15 years to go, we’re two-thirds of the way to the goal line. On the past-decade trendline, the target will be met in 2021.

The 2005-2015 rate of decline in power-sector emissions is so far ahead of the CPP that it could be cut by two-thirds going forward and the 32 percent reduction goal would still be met.

The math is elementary, but it bears emphasis in light of the discussion swirling around last week’s debate in St. Louis over the effort of the Bernie Sanders – Bill McKibben forces to ramp up the climate-policy language in the Democratic Party’s 2016 platform. This is from Ben Adler’s take in Grist:

The Clinton campaign says its reluctance to accept some of McKibben’s amendments reflects legitimate concerns about the policy implications, not mere political calculation. Not all experts agree that a carbon tax is the most effective way to reduce emissions, for example. Mary Nichols of the California Air Resources Board had pointed out in her testimony to the committee a week earlier that a carbon tax does not guarantee emissions reductions, while direct regulation, such as Obama’s Clean Power Plan, does.

Former Bill Clinton and Obama official Carol Browner also leaned heavily on Nichols’ testimony in her remarks in St. Louis in leading the charge that narrowly defeated the McKibben carbon tax, as we noted in our recent post on the debate.

The irony of course is that the Clean Power Plan didn’t actually “guarantee” much of anything, insofar as the plan’s targeted reduction has been happening more or less on its own.

But if power-sector emissions are falling so easily, why bother with a carbon tax at all?

For a lot of reasons. Here are the key ones:

- First, the U.S. needs to blow way past a 32 percent shrinkage in power-sector emissions over 25 years.

- Second, non-electricity emissions of CO2 — now 63 percent of the U.S. total — have fallen little, dropping from 2005 to 2015 by just 190 million metric tons as electricity emissions were falling by 518 million. The majority of those emissions are from gasoline, diesel, jet fuel and other petroleum products, underscoring the importance of offsetting the nearly historically low petroleum prices that businesses and consumers are “enjoying” today and banking on in the future, with carbon taxes.

- Third, we need to shrink not just emissions but the financial and political power of the oil industry. We’ve got to break the cycle that allows fossil fuel corporations to lock in policies — including the “right” to dump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at no charge — that lock in demand for their product. A carbon tax will help crack that open.

We’ve never underestimated the difficulty of enacting robust carbon taxes in our nearly-closed political system. One piece in many to get us there faster is for the climate movement to see that the Clean Power Plan is yesterday’s plan. As we argued in our prior post, the core of our plan going forward must be Bill McKibben’s carbon tax resolution from St. Louis:

Carbon and other greenhouse gases should be taxed at a rate high enough to spur the transition away from fossil fuels consistent with the temperature goals agreed to in Paris in 2015.

Note: The data underlying our graphic may be found in CTC’s carbon-tax spreadsheet model (Excel file).

Going Here

Time for Climate Advocates to Move Beyond the Clean Power Plan