The Brookings Institution is out with a handsome new report, State-Level Carbon Taxes: Options And Opportunities For Policymakers. We’re still digesting it, but it looks like one of the most lucid and useful publications on carbon taxes to appear in a long time. At a minimum, it’s essential reading for at least two (overlapping) groups: people seeking to advance carbon taxes at the state level, and people who want to steep themselves in the nuts and bolts of implementing actual carbon taxes.

The authors are three heavy hitters in carbon tax policy and advocacy: Adele Morris of Brookings, Yoram Bauman of Carbon Washington, and David Bookbinder of the Niskanen Center. Together they bring to bear key disciplines (economics, law, political organizing), extensive knowledge, and keen interest. It’s no surprise their report is a winner.

Here’s the start:

Much has been written about the design of a federal-level carbon tax. This paper adapts these findings to the state level, motivated by pending federal regulations (which place implementation obligations on states), policy discussions in states with commitments to ambitious long-term emissions targets, and state budget shortfalls that could necessitate new revenue. Notwithstanding the myriad political impediments to a carbon tax, this paper explains how state policymakers can design one to fit their fiscal, economic, distributional, and environmental goals.

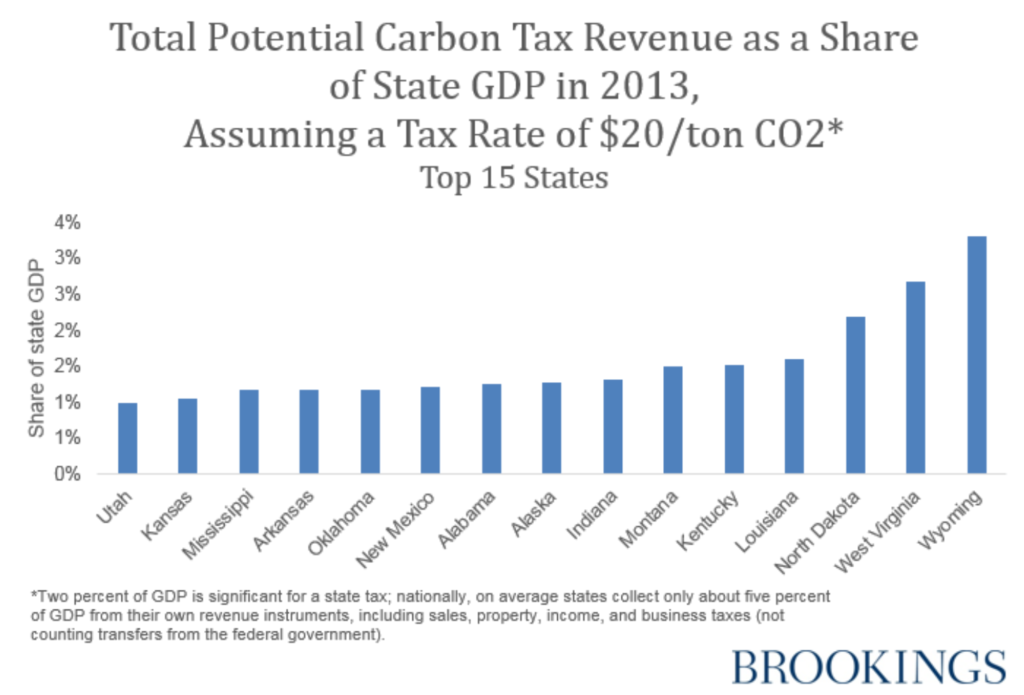

They find that “a $20 per ton tax on energy-related CO2 emissions could raise up to 2-3 percent of state GDP in the most emissions-intensive states.” That is significant, they say, because current state revenue instruments — sales, property, income, and business taxes — typically collect only about 5% of GDP. Moreover, contrary to the usual view that a carbon tax might be an unreliable revenue generator, if only because the revenue base of carbon emissions would shrink over time, the report concludes that carbon fees could prove less volatile than other state revenue sources.

Graphic is from Brookings issue brief (see link at end).

While carbon fees of $20/ton are almost certainly far lower than the levels needed to fully drive the transition of the U.S. economy to a low-carbon base, it’s a reasonable level for considering state taxes, given issues of leakage, interstate competition, and poorly diversified state economies. In any event, the report’s insights into state carbon tax implementation don’t depend on any particular tax level.

For all 50 states plus the District of Columbia, annual revenues from applying $20/ton state-level carbon taxes to all fossil fuel combustion would total $106 billion, based on 2013 emissions and assuming, for simplicity, zero price-responsiveness. That’s around two-thirds of one percent of combined state GDP. But the range is enormous, from a low of around 0.3 percent (for California, Connecticut, and Massachusetts; here we exclude DC, for which the tax revenue would equate to just 0.05% of GDP), to more than 2 percent for North Dakota and West Virginia and more than 3 percent for Wyoming. (See graphic; Wyoming was inadvertently omitted.)

Tellingly, of the 15 states with the highest shares of potential carbon tax revenues relative to GDP, 14 are “red” on the political map. Only New Mexico voted for a Democrat, President Obama, in 2012 (and 2008). The correlation of carbon-dependence with electoral conservatism underscores (and reflects) the political polarization over climate belief and carbon-reduction policy. And while organizing for state carbon taxing has been exclusively focused on low-carbon blue states such as Washington and Massachusetts, the sheer fiscal potential of carbon taxes in the states shown in the graphic suggests vast untapped potential to transform state economies from fossil-fuel extraction to a broader and more sustainable base.

The Brookings report is far richer than mere figures and graphs. It dives deeply but clearly into thorny questions like interstate transport of fuels and electricity, and harmonizing of state carbon fees with EPA Clean Power Plan requirements, that haven’t arisen at the federal tax level. Issues of federal pre-emption (e.g., for aviation fuels), compliance with the “dormant” Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, and revenue usage are treated as well. The report is also richly referenced and annotated.

Whether or not the path to a U.S. carbon tax will need to wind from one or a few early-adopting states to Congress can’t be predicted. Regardless, the Brookings report is both a masterful summation of state carbon tax issues and a vital read for anyone pursuing carbon pricing in the United States.

Link to the full 32-page Brookings report: State-Level Carbon Taxes: Options And Opportunities For Policymakers

Link to the Brookings issue brief (contains graph shown above): What to consider when designing a state-level carbon tax

discount vouchers days out yorkshire

Brookings report on state carbon taxes is a winner