The surprise wasn’t the front-page New York Times headline, “Diplomats Confront New Threat to Paris Climate Pact: Donald Trump.” It was inside, as The Times gave voice to concerns from America’s two top trading partners that U.S. backtracking on carbon emissions would give American exports an unfair trade edge and compel them to slap carbon tariffs on our products.

Posturing? Perhaps. But perhaps something more.

“A carbon tariff against the United States is an option for us,” Mexico’s under secretary for environmental policy and planning told Times climate reporter Coral Davenport. “We will apply any kind of policy necessary to defend the quality of life for our people, to protect our environment and to protect our industries.”

According to Davenport, “Forcing United States industries to turn to cleaner energy sources with the hammer of an import tariff is not far-fetched.” As she explained it:

Countries imposing costs on their own industries to control carbon emissions could tell the World Trade Organization that U.S. industries are operating under an unfair trade advantage by avoiding any cost for their pollution. The tax would be calculated based on the amount of carbon pollution associated with the manufacturing of each product. That would impose a painful cost on the heaviest industrial polluters, particularly on exporters of products containing steel and cement.

(Our Web site devotes a full page to carbon tariffs, a/k/a border tax adjustments.)

Canada “is also discussing a tariff,” Davenport reported. After noting that Ontario and Quebec (along with British Columbia) “already have carbon tax policies that include fees imposed on fossil-fueled energy generated across provincial borders,” she quoted a Canadian attorney specializing in climate and trade: “I see that extending across the Canadian border if the U.S. pulls out of Paris. If you want to sell your goods in Canada, you’d have to meet the same emissions standards.”

The irony is that virtually all past policy discussions of carbon taxes and trade centered on the United States’ supposed need for carbon tariffs to ensure a level playing field with imports from non-carbon-taxing countries. With president-elect Trump now vowing to walk away from the Paris Agreement and pump up fossil fuel burning, the shoe has switched to the other foot.

To be sure, the rumblings from Mexico and Canada have an element of posturing. They resound with domestic audiences, although not enough for former French president Nicolas Sarkozy, who raised the carbon tariff idea last week but lost the conservative party’s nomination in Sunday’s vote. Nevertheless, the appeal of carbon tariffs is undeniable. Protecting both domestic jobs and the climate makes a potent one-two punch.

But what if the threat of trade wars could keep Paris intact?

The potential downside is also two-fold: provoking the powerful USA, and igniting a trade war. Davenport quoted several sources who tamped down the idea of carbon tariffs on U.S. goods. Although one was a Koch Brothers factotum, others, from China and the European Union, dismissed such talk as premature and potentially risky.

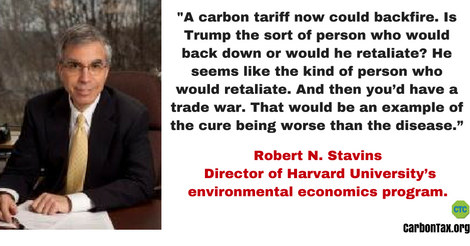

Another dissenter was Harvard economist and climate specialist Rob Stavins, who fretted that carbon tariffs against U.S. goods might ignite a retaliatory trade war. “That would be an example of the cure being worse than the disease, Stavins warned.”

But would it? Short of World War III, what remotely foreseeable disaster could be worse than breaking the Paris Agreement and sending the world spiraling down toward climate ruin?

All the same, carbon tariffs are best deployed as leverage, and perhaps only as a last resort. Even conveying such a threat must be done deftly. But Nov. 8 has upended the global climate applecart. “[I]f one big country backs out [of the Paris Agreement] it could trigger a whole wave of trade responses,” said Dirk Forrister, CEO of the International Emissions Trading Organization. As Forrister told Davenport of the Times:

A carbon tariff is a power tool. It’s not one that any country would use lightly. Things would have to get pretty serious for any country to take it out of the toolbox and use it. But given the current situation it’s a possibility that they would do it.

Things are serious all right. The time to wield a possible carbon tariff may be coming sooner than anyone imagined.

Drew Keeling says

James Hansen’s carbon tax advocacy, seven years ago (at least), also explicitly incorporated the possibility of carbon tariffs.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/dec/27/james-hansen-copenhagen-agreement-opportunities