Supporters of nuclear power wasted little time pointing out how much carbon-free electricity production will vanish from closing the Indian Point reactors 25 miles north of New York City.

As the New York Times reported last Friday, NY Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Entergy Corp. have reached an agreement to shut the twin reactors permanently in 2020 and 2021, respectively. Both units are in their fifth decade of operation. Though their electricity output has finally attained consistently high levels, their checkered record and proximity to New York City have made them an abiding source of concern of safe-energy activists as well as the state’s governor and attorney general.

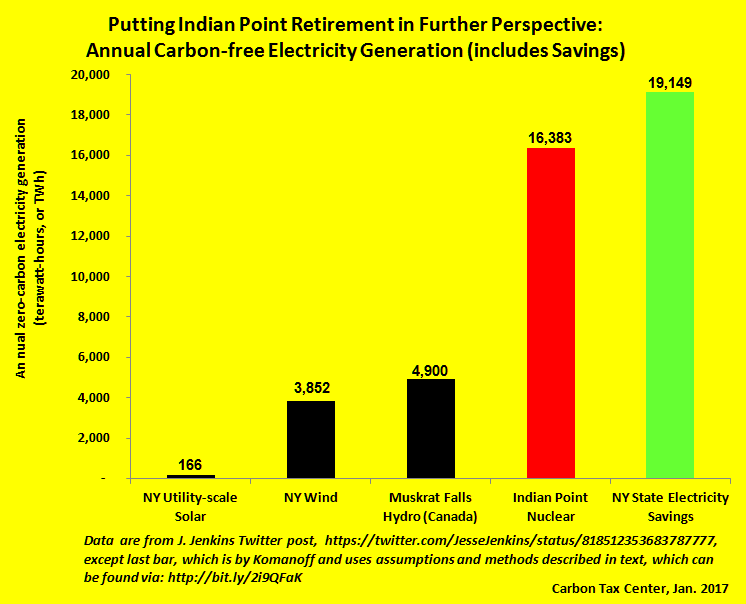

Replacing Indian Point with 100% carbon-free energy will be a tall order, according to one researcher. See graph below for a different take.

Like most operating nuclear power facilities, Indian Point produces a good deal of nearly carbon-free electricity. Charges by some antinuke activists that reactors have sizable carbon footprints are overblown. Most rely on outdated assumptions (e.g., that uranium “enrichment” still takes place in power-guzzling Cold War-era plants) or questionable accounting (charging today’s reactors for putative energy costs of far-future waste storage).

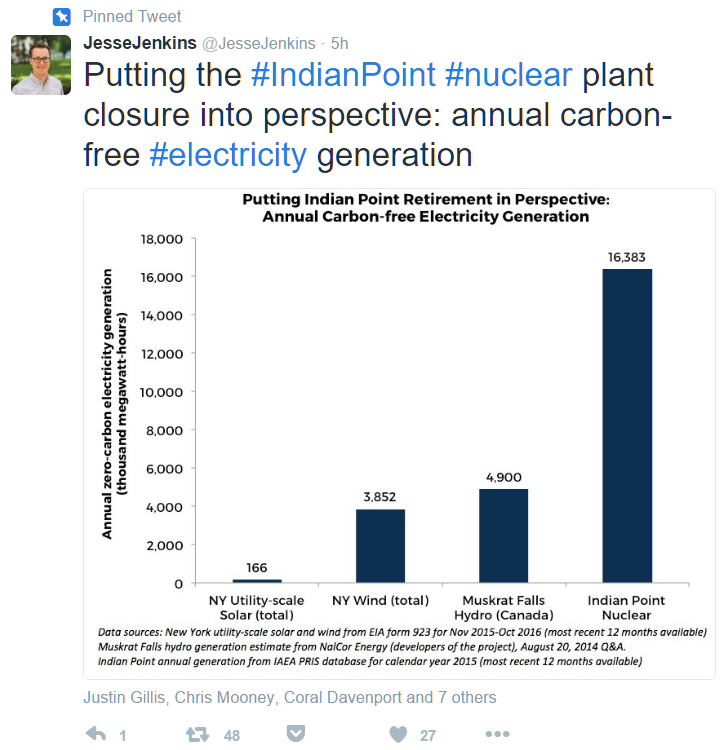

That production gave rise yesterday to the tweet shown at left from Jesse Jenkins, an electricity researcher with the Breakthrough Institute, purporting to “put the Indian Point plant closure into perspective” by showing that its electricity generation dwarfs that of other New York state sources of carbon-free energy.

Jenkins’ figures are probably right (I haven’t checked them, but he’s good with numbers). But they’re incomplete. They omit New York’s share of the largest U.S. source of carbon-free electricity in recent years: the electricity savings embodied in the divergence of total electricity usage from total economic activity.

We quantified that divergence in a new report last month, The Good News (blog summary version here). The bottom line, in numerical terms, is that in 2016 the U.S. was able to avoid generating a little over 500 TWh of electricity — almost one-eighth of the electricity it did produce — because electricity usage barely grew compared to 2005 consumption. (A TWh, one billion kWh, is a convenient metric.)

For reasons we spelled out in the report — structural shifts from energy-intensive heavy manufacturing to service industries; ratepayer-funded efficiency programs in tandem with government codes and standards for buildings, appliances and other end-use equipment; rapid penetration of digital technologies in energy management, product design and manufacturing, to name several — U.S. electricity generation in 2016 will likely be a mere 20 TWh above the 2005 level of 4,056 TWh, rather than in the 4,500-4,600 TWh range it would have reached if nationwide demand for power had grown after 2005 at the same relative rate to GDP that held during 1975-2005.

Estimated NY electricity savings are surpassing Indian Point’s carbon-free output.

Almost by definition, those electricity savings are widely distributed and have taken place in every state. New York’s share may have been greater than the national rate, given its concentration of large office buildings and multifamily housing that are particularly ripe for money-saving energy-efficiency retrofits. For conservatism, we assign 3.8 percent of the 507 TWh of national avoided generation in 2016 to New York, based on its share of U.S. electricity usage in 2014, the most recent year with state data.

That works out to 19.1 TWh of electricity generation avoided statewide last year — all of it carbon-free — because the economy here, in tandem with the country as a whole, reduced its electricity-intensiveness between 2005 and 2016. (We use 2005 as a baseline because it’s both the benchmark year for many climate policy targets and the year in which U.S. electricity use began to markedly detach from economic output.) That figure surpasses by a wide margin the 16.4 TWh of annual electricity production that Jenkins ascribes to Indian Point, as our expanded chart shows.

It is true that electricity savings and nuclear power generation aren’t necessarily in conflict. Shutting Indian Point will require New York State policy, investment and consumers to push harder — much harder — on wind and solar as well as energy efficiency to achieve the carbon reductions that Indian Point now provides and would keep providing if the plant were re-licensed and continually refurbished to permit it to operate indefinitely.

But it is also true that Indian Point isn’t fully complementary with efficiency and renewables. The reactors’ inability to easily vary their output makes it harder for the state electric grid to integrate naturally variable wind turbines and solar power. Indian Point’s presence on the grid also depresses the prices offered for renewable electricity and energy savings alike. Conversely, the prospect of terminating both reactors several years from now will expand the horizons for carbon-free electric energy in New York state on both the supply and demand sides.

We hope this post adds useful context to Indian Point’s now-pending closing. It has been a major source of carbon-free electricity for New York state, but as of 2016 it’s no longer the pre-eminent one. Recognizing the contributions of energy efficiency in reducing greenhouse gas emissions will make it easier to fashion policies and organizing strategies that protect our climate, with or without nuclear power.

Hamilton Fish says

I thought Charlie’s followers would enjoy a little background on the recent agreement on closure at Indian Point. We have a signed and binding agreement in place to close the two remaining active reactors. A lot of history has led us to this outcome, decades of advocacy and activism on the part of dozens of courageous people from Pete Seeger and Connie Hogarth to Bob Boyle and Bobby Kennedy Jr, but the honor roll on the closure of Indian Point now has to begin with Governor Andrew Cuomo – a politician who delivered on a promise. Riverkeeper – the clean water and Hudson River advocate that I was privileged to represent in these difficult negotiations, alongside our president and chief negotiator Paul Gallay – has lobbied for more than a generation to improve plant safety and argued relentlessly against continued operations. We’ve learned from recent inspections that more than a quarter of the bolts that hold the inner walls of the Reactor 2 core were either missing or damaged. The bolts in Reactor 3 have yet to be tested. The plant is plagued with problems – there are unsustainable levels of radioactivity in the nearby groundwater, and just in the past eighteen months the inventory of harrowing and documented crises have included electrical failures (including a transformer explosion, a water pump failure and a power failure affecting the control rods in one of the reactors), a major oil spill, blocked drains and flooding of compartments containing key plant safety equipment, and seven unplanned shutdowns.

Every party to this agreement had their own motivations. As Attorney General, Eric Schneiderman has had a distinguished record on plant closure and public safety. Entergy, the plant’s owner and operator, has faced continuing and enormously costly challenges to its relicensing application from both the State and a galvanized public interest community, as well as increasing competition from cheaper sources of power. The State agencies that were party to the agreement also had a stake in the outcome – the Department of Environmental Conservation has either modified or denied Entergy’s applications for water quality and pollution discharge certificates, and the NYS Department of State had denied Entergy a critical certificate required under its Coastal Zone Management Program (a decision later upheld by the State Court of Appeals).

There is still a long road ahead – we need to find creative ways of helping displaced workers adjust to closure, and to assist the villages and towns in the vicinity of Indian Point whose schools and libraries have been funded in part by tax revenues generated by the plant. We can more than offset the loss of Indian Point’s 2000 megawatts of electricity through efficiencies and innovation, and by continuing to develop reliable and renewable sources of replacement power like the offshore wind and hydro-electric projects the State energy czar Richard Kauffman is helping to put in place for New York. But for the tens upon tens of millions of people who live and work within the penumbra of danger from a potential radioactive event at this unstable nuclear plant, their lives have just been immeasurably improved.

Robert Jereski says

Thanks for this post. Very interesting. Question: you write: We use 2005 as a baseline because it’s both the benchmark year for many climate policy targets and the year in which U.S. electricity use began to markedly detach from economic output. Does the measure of U.S. economic output include the sale of manufactured goods produced by U.S. companies operating in China? How does the energy intensity of this production factor into these calculations? Alternatively is the energy intensity of non-U.S. manufactured goods increasing and is US per capita consumption of these goods increasing?

Not sure this makes sense or is relevant. Thanks!

Joshua Goldstein says

The “savings” from energy efficiency are only savings relative to growth that might otherwise have happened. Emissions didn’t go down. But taking away nuclear generation increases real emissions. In Vermont, California, and Germany, closed nuclear plants were replaced with fossil fuels. If you think that’s a good trade-off because nuclear is too dangerous, then fine. But it doesn’t help to pretend that nuclear can be decreased without raising carbon emissions. Even if solar, wind, and hydro are growing, those can’t replace coal and natural gas if they have to replace a closed nuclear plant. A rational debate is needed about how dangerous and urgent is climate change and how dangerous and urgent is nuclear power.

Charles Komanoff says

I thought I said as much in the post:

I also tried to say that the carbon costs of reactor closings need to be put in context vis-a-vis the greater benefits from electricity savings.

Nuclear power has tantalized smart and well-meaning for 70 years. After analyzing and tracking it intensely from the mid-70s to the mid-90s, I’ve come to the view that its distractive impacts as well as financial costs aren’t worth the putative benefits.