Years ago, my friend Vince built a house on a hillside in Vermont, a mile or so from the town where he grew up. The deck looked out on the valley and, at night, to a dark sky filled with stars. Then a couple from Montreal, weekenders, put up an A-frame in the valley, with an outdoor light that obliterated the darkness. When they drove back to the city on Sundays, the light stayed lit.

Vince had a choice: try to reason with the couple, or direct action. It was either-or, since talking with them would blow his cover. He chose direct action: One Monday evening he drove over with a ladder and unscrewed the bulb. Evidently the couple didn’t take the hint, since the light went back on the next weekend. The following Monday, Vince returned with a friend, who brought his shotgun. The light went off and stayed off.

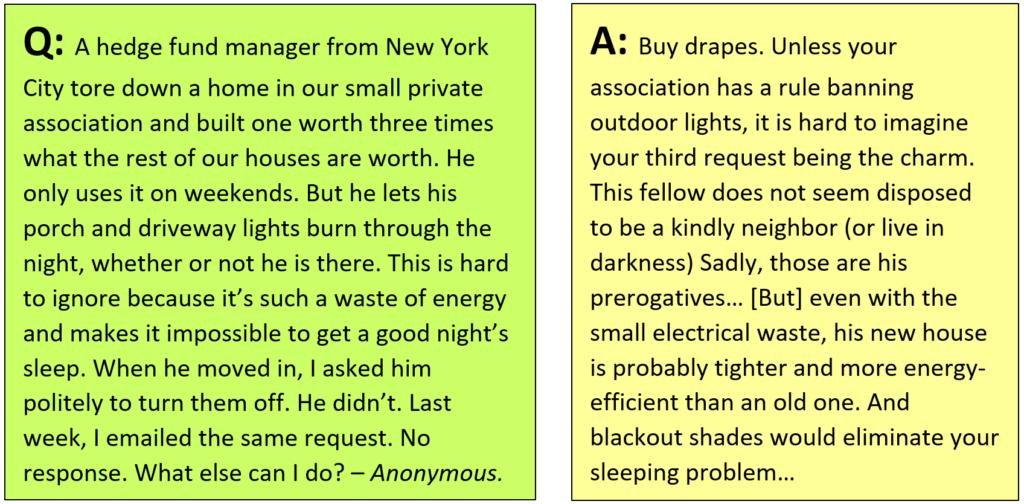

From Feb 5 NY Times etiquette column, under heading ‘Waste of Energy.’

What brought this episode to mind was the letter in the Sunday NY Times’ etiquette column, Social Q’s, shown at left, about a glaring light in a homeowners’ association. The letter-writer bemoaned the waste of energy rather than the loss of dark sky. But chalk one up for Vince from Vermont; reasoning didn’t avail, leaving the letter-writer to suck it up and “buy drapes.”

A small, sad story. Of greater interest is what the columnist said — and neglected to say — in response, about energy, climate and the social compact.

The columnist rationalized the hedge fund manager’s waste of electricity by citing the advance of energy efficiency. New homes, indeed new everything, from appliances and computers to automobiles and aircraft, are required to be more energy-efficient — the result of a hard-won societal decision to build efficiencies into product design rather than leave them to an energy marketplace whose prices don’t fully reflect environmental costs. The point of energy standards is to bridge those marketplace gaps, not provide an excuse for unfettered waste.

And think about how much energy usage has to be eliminated to meet even the most basic climate targets. Running in place doesn’t pass muster when carbon emissions need to shrink 80 percent by 2050 if not much sooner. We’ve run out of room for backsliding.

Milky Way. Photo by Hans Braxmeier, via Pixabay.

I’ll bet the letter-writer gets that. To her, the waste of electricity probably goes beyond the btu’s and CO2. It’s a signifier of the neighbor’s heedlessness. Though he’s not legally required to have climate-consciousness, it’s frustrating that he apparently doesn’t. Making things worse, there’s no carbon tax. While a stiff carbon emissions charge might not change the neighbor’s behavior, our letter-writer might gain a measure of satisfaction from knowing that the neighbor’s heedlessness is adding to tax revenues.

The columnist’s reply also ratifies our asymmetrical social compact: it’s the neighbor’s prerogative to light up the night, and the letter-writer’s responsibility to deal with the damage. The same social compact lets helicopter users and jet-skiers destroy quiet enjoyment of the world for the rest of us. Go ahead and spew unwanted light, unwanted sound, unwanted greenhouse gases; we’ll put up with the damage.

The columnist didn’t suggest collective action. Shouldn’t the letter-writer talk to other neighbors and try to organize them? Okay, maybe that’s futile, or maybe she risks being labeled a crank or squandering social capital she might need for some bigger concern. And there are only so many hours in the day.

The moral: in energy and climate, as in anything, there are norms at play. As I pointed out years ago, in my post, No Magic Price Point for Kicking Carbon, so much energy use that we think is necessary or natural is actually socially determined. Cheap energy has engendered a culture of conspicuous usage and waste. A carbon tax could help dismantle that, and undo much of the ingrained consumption that gets under our skin.