This post was researched and written by CTC intern Michael Kendall. More recent info, including 2016 carbon emissions data, are in the U.K. section of our Where Carbon Is Taxed page.

The United Kingdom, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution and a kingdom built on coal, has cut emissions of carbon dioxide to levels not seen since the late 19th Century, according to a report from the UK consultancy, Carbon Brief.

CO2 emissions from fossil fuel burning in the UK (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) totaled just 381 million metric tons (“tonnes”) last year, a 6 percent decrease from 2015 and 36 percent less than levels in 1990 (or 44 percent less than levels in 1970 when CO2 emissions peaked at 685 tonnes).

As Carbon Brief noted, total UK emissions hadn’t been that low since 1894, save for 1921 and 1926, when miner strikes paralyzed the coal industry.

No more carrying coals to Newcastle, as the historic but filthy fuel disappears from the UK.

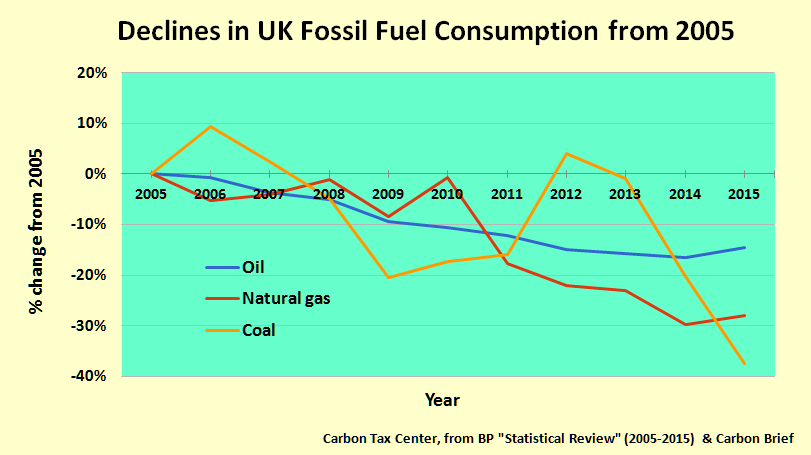

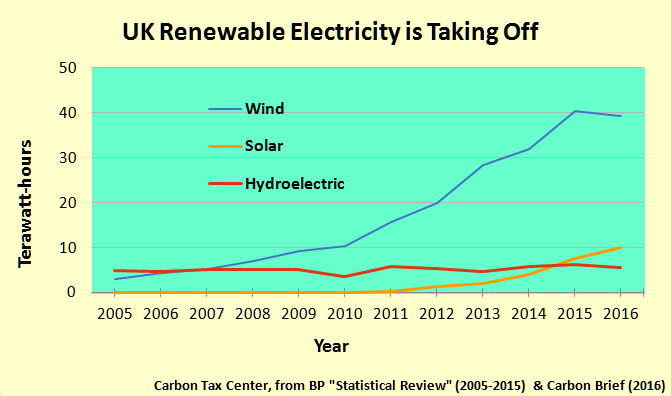

Coal burning is disappearing from the former perennial bastion of coal, while use of oil and gas is down considerably from 2005, despite upticks since 2014 for both fuels. At the same time renewables are thriving, with a Carbon Brief analysis showing that wind generated more electricity throughout the UK than coal in 2016.

Data from British Petroleum’s comprehensive annual Statistical Review of World Energy show coal consumption in 2015 down 38 percent from 2005. That steep drop has driven down total CO2 emissions from UK fossil fuel combustion nearly 25 percent over the same period. (The UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy will release official figures later this month.)

These reductions stem from a coordinated effort to cut emissions, reliant upon setting a national price on carbon in 2013. “Perhaps the most consequential factor,” says Carbon Brief editor Simon Evans, “is the UK’s top-up carbon tax, which doubled in 2015 to £18 per tonne of CO2.” (Brits sometimes refer to their carbon tax as a “top up” tax since it was intended to top up the carbon price determined via the auctioning of emission permits under the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme.)

The UK carbon tax equated to $24-$25 per short ton in 2016, at last year’s average 1.5-to-1 sterling to dollar exchange rate (the exchange rate is a good deal lower at this writing in 2017, however), and converting metric to short tons. A carbon tax targets coal above all, on account of coal’s higher carbon content per Btu compared to oil or gas, which enhances the profitability and deployment of zero-carbon substitutes for coal-fired electricity, such as wind. And in fact Evans has charted the month-by-month collapse in coal use.

UK wind turbines generated more electricity than coal-fired plants in 2016, reports Carbon Brief.

Last week Drax, an energy generation company specializing in biomass, presented commissioned research taking carbon pricing a step further. The researchers modeled the likely impact on use of coal and natural gas and CO2 emissions from alternatively removing or doubling the UK carbon tax. Their models show that without the carbon tax, coal generation would have doubled and emissions would have risen 21 percent, significantly undercutting past emission gains; whereas doubling the tax would have cut coal generation by an extra 47 percent and shaved another 10 percent off overall CO2 emissions.

Continuing the good news: belying the standard notion that pricing carbon emissions must increase household energy bills, UK households paid less in energy bills (gas plus electricity) in 2016 than they did in 2008. We’ll look to Simon Evans for a summary:

Since 2008, household consumption of gas is down by 23% and electricity by 17%, cutting the average bill by £290 and more than offsetting the increase in policy costs over the same period… These energy savings are largely the result of energy efficiency policies and regulations, from UK rules mandating more efficient condensing boilers to EU product policy on more efficient fridges and ovens.

In short, while the price per kWh of electricity has risen for UK households, improvements in efficiency have cut household usage even more, enabling total household costs to fall. This stands as a model instance of regulation working in tandem with carbon pricing, as more-efficient appliances became more available due to regulation and more attractive due to the higher unit cost of electricity.

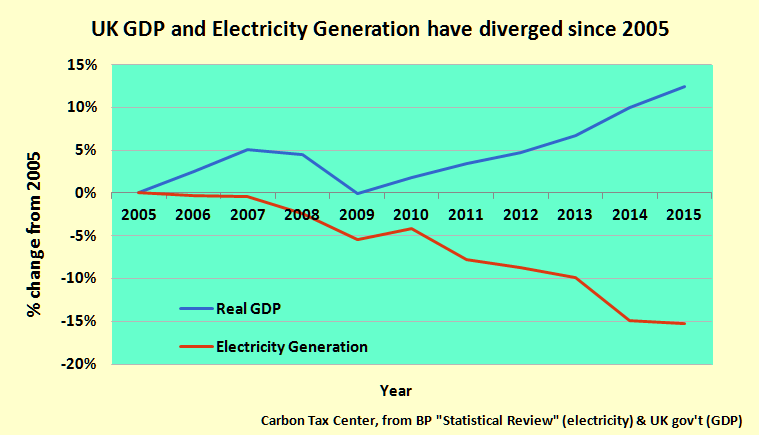

An unprecedented 15 percent drop since 2005 in electricity generation has helped drive down emissions as the UK economy has grown.

A further dividend of electricity savings, of course, is that the nationwide increase in electricity from wind turbines and gas-fired generation has been at the expense of coal rather than in addition to it — mirroring the U.S. experience since 2005 that we distilled and quantified in our December report, The Good News.

Where does the carbon tax stand now, with last year’s Brexit vote set to remove the UK from the European Union? The government’s March 2011 Budget set a 2020 target of a £30 per tonne tax on CO2, but in 2014 that figure was reduced to £18 via a price cap until 2020. In 2016 this cap was extended to 2021 “to limit the competitive disadvantage faced by business and reduce energy bills for consumers.” (See “The Carbon Price Floor” House of Commons briefing paper, p.3.)

Last week’s Spring Budget 2017 is vague about the future of the carbon price floor, stating that the “government remains committed to carbon pricing” but reserving details until the Autumn Budget 2017. The most promising statement in the budget is this, at page 34: “Starting in 2021-22, the government will target a total carbon price.” It suggests that the UK intends to continue to price carbon despite the country’s imminent exit from the EU. Carbon Brief provides a fuller analysis of the Budget’s potential impact on climate policy.

Dr. Luis Contreras says

Are you including the carbon emissions of the DRAX 4000 MW coal plant using wood pellets from U.S. forests? I am all for carbon fee and dividend, but if you are counting burning wood pellets as “clean or renewable” the report is invalid. Sorry.

Here is a Daily Mail report on DRAX: The UK’s £1billion carbon-belcher raping US forests…that YOU pay for: How world’s biggest green power plant is actually INCREASING greenhouse gas emissions and Britain’s energy bill

Drax power station in Yorkshire uses wood pellets to create electricity

The move from coal was considered to be environmentally friendly

But far from cutting emissions, change is actually increasing them

In turn, it is adding millions of pounds to Britain’s electricity bills

Charles Komanoff says

The CO2 from combustion of wood pellets at the Drax coal-fired (now coal plus biomass fired) power station isn’t included in the 381 million metric ton figure for total UK 2016 CO2 emissions. International conventions assign those emissions to land use and forestry in the home country (the US in this instance). Nevertheless, those emissions aren’t huge in this instance. Wood pellets account for about half of the fuel burn at Drax. Assuming a 90% capacity factor, the emissions attributable to the wood pellets are around 4 million metric tons, or 1 percent of the 381 million figure — an adjustment that hardly “invalidates” the findings that Dr. Evans published in Carbon Brief and that we summarized here.

Your point is important, however. Accounting for carbon emissions from biomass burning is vexing, as we explain on our Web page, Should a Carbon Tax Apply to Bioenergy? We welcome your comments and suggestions.

Bart R says

Rubino et al (2013) permits a compelling case for excluding biogenic carbon from all CO2e emission figures, in that the isotopic pC13 ratio of carbon in the atmosphere shows only fossil carbon contributing to the massive CO2 spike since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

This is not to argue that there is some magic daemon picking and choosing where carbon goes based on its origin, but only that in the accounting if we burn wood for power or if bacteria convert cellulose to methane, biogenic carbon is largely a wash while fossil carbon is an added burden on weathering and sequestering sinks.

As such, whether you burn organic matter, eat meat that obtained its carbon from grass, or soil microbes digest the grass when it falls and mulches, carbon moves through the short carbon cycle at the pace of the short carbon cycle, which humans make relatively little difference to overall, compared to fossil waste dumping.

Indeed, founding an industry where producing efficient profit pushing fossil off the market while delivering locally secure, fossil-free power could promote sequestration of biogenic carbon more, if the fuel production method is pyrolysis, and the fixed-carbon byproduct biochar (itself a very useful good) is sequestered, leaving only the relatively low-carbon volatile distillates and producer gas for burning..

Bart R says

As you are welcoming comments and suggestions,on “Should a Carbon Tax Apply to Bioenergy?” it may be prudent to suggest adding a comments section to that web page. 😉

One point often overlooked is biofuel’s dual nature both as a near alternative and as a complementary good.

As a near alternative, it is feasible for biofuel to displace fossil from the market, thereby keeping fossil carbon in the lithosphere and biogenic carbon in the biosphere segretated, without the many disruptions of acidification (and consequent affect on heavy metal levels in treated water), climate change (and extreme weather), crop nutrient density loss and soil fertility depletion. This substitution effect clearly is both a public and a private good, in that biofuels can be less costly to consumers than fossil, and in t he case for example of fossil from bitumen are much cheaper, while the environmental benefits are clear.

As a complementary good, biofuel that stretches fossil, as ethanol additives do, especially where the biofuel production itself is fossil-intensive, is clearly a public harm and not a great private benefit, a shell game of subsidy, entitlement, infrastructure spending, expropriation and regulation that ultimately costs more in taxes, interest expenses .and lost opportunity while doing nothing good for the public.

Where there are ways to create biogenic fuel, the less good options (like ethanol) are the enemy of the better options.like pyrolysis. These processes must compete with each other on a playing field set for the public interest to win, including an effective way to separate net-fossil increasing from net-fossil negative, and pricing the options accordingly in the Market.

Glyn says

There is no inclusion of soil carbon loss, or soil carbon drawdown through the process of photosysisus where CO2 is drawn out of the atmosphere and exchanged for soil nutrients with soil microorganisms back into the soil wence it came.. 60 % or more GHG emissions come from disturbed soil and no mention in the report of the worlds biggest carbon store / emitter – soil.