Guest post by Jessica F. Green, assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Studies, New York University. This post is adapted from the longer original version published last month in Nature.

Carbon trading programs are proliferating. These allow companies to buy and sell the right to emit carbon dioxide. The European Union’s Emissions Trading System covers 11,000 emitters across all EU member states, as well as Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. California and Quebec share a market, which Ontario, Manitoba and provinces in Brazil and Mexico plan to join. China is due to launch its national cap-and-trade system later this year, comprising 7,000 emitters.

Around 100 nations have said they are planning or considering carbon pricing to reach their emissions-reduction goals in the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change, according to the World Bank’s State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2016 report. These pricing plans include carbon taxes and trading schemes.

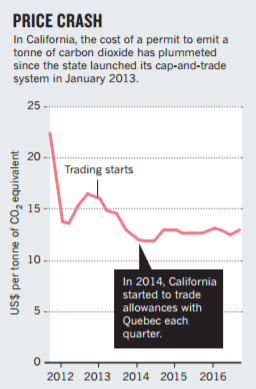

(Graphic is from original version of this post, in Nature magazine.)

Many policymakers are urging that cap-and-trade programs be linked together in a global carbon market. According to prevailing economic theory, linking markets together should promote trading, smooth financial flows and lower the overall cost of reducing emissions. A global price on carbon emissions would emerge without the need for long and fractious diplomatic negotiations.

But reality is more complicated. Initial attempts to join up trading schemes in Europe, California and Quebec have led to price crashes and volatility, not stability. It is becoming clear that cap-and-trade works only under special circumstances — when one entity controls the market and parallel initiatives do not undermine it.

Single carbon markets are difficult to manage; this becomes even more challenging when many regulatory authorities compete in linked markets. Interactions with other climate policies trigger unintended outcomes. Policymakers find it hard to keep prices at the ‘right’ level — neither so high that a carbon market becomes politically unacceptable, nor so low that it fails to change behavior. As I show below, California’s case shows that lawmakers can be tempted to use regulatory loopholes to drive down prices and weaken the market’s effectiveness. Such problems will only worsen when more markets are linked up.

So, policymakers should keep it simple. A truly global carbon market would need a central carbon bank to manage allowances and prices. But that approach seems unlikely in today’s political climate. In the absence of such a body, national and regional carbon markets should maximize their autonomy, manage their own prices and regularly ratchet down the caps on total emissions. Prices must be kept high and regulatory loopholes avoided for net emissions to fall.

Lessons From Acid Rain

Proponents of carbon markets often trumpet the success of the US Acid Rain Program. In 1990, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) created a nationwide market for sulfur dioxide. The agency capped the total amount of the gas that could be emitted nationally, and gave allowances to power plants on the basis of their past SO2 emissions. The plants could then trade these allowances.

Between 1990 and 2004, the sulfur cap-and-trade program reduced US SO2 emissions by almost 6 million metric tons (“tonnes”), a roughly 35% drop, even as US electricity generation increased by almost one-third. By 2010, SO2 emissions had halved again to 5 million tonnes. Compliance was close to 100%. The health benefits alone were estimated to exceed $50 billion a year — a bargain, given that the program’s annual administration costs were about $0.5 billion.

Enthusiasm grew for cap-and-trade mechanisms to manage other pollutants. During the Kyoto Protocol climate negotiations in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the idea of an international carbon market took hold. The protocol created the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which in 2005 became the first global exchange for carbon offsets, allowing countries to receive credit for financing emissions-reduction activities outside their borders. The same year, the EU created its Emissions Trading System, which it linked immediately to the CDM. This allowed companies to pay for offsets abroad through the CDM as a way of meeting their EU emissions quotas.

But the Acid Rain Program was a special case. It ran under the sole authority of the EPA. Power plants that did not comply faced onerous financial penalties: $2,000 per tonne of emitted SO2, compared to €100 (US$106) per tonne of CO2 for the EU-ETS. Moreover, the EPA program began as a closed regulatory system. Policymakers deliberately avoided adding other policies such as technology requirements or performance standards to reduce SO2 emissions. By contrast, carbon markets are influenced by other policies on climate change and energy.

The second phase of the Acid Rain Program shows how problems arise when a closed regulatory system is opened up. In 2005, the EPA created the Clean Air Interstate Rule to target nitrogen oxides, too. This tightened the cap on SO2 emissions, widened the program to cover more US states and made trading optional.

The changes led to a spike in prices. At the same time, a number of downwind states sued the EPA on grounds that the changed rules were too lax. The suit was successful and gave rise to new regulations. The market became volatile and, eventually, irrelevant. Now, SO2 trades at a few cents per tonne. Emissions continue to fall, and are down more than sevenfold from 1990 levels. The rise in supplies of natural gas and increased availability of low-sulfur coal also played a part.

Mixed Messages

Attempts to join up carbon markets have faced similar challenges. There are two notable examples: the EU-ETS link with the Kyoto Protocol’s CDM, and California and Quebec’s shared market.

In mid-2008, EU-ETS carbon prices plummeted from roughly €25 to less than €10 per tonne of CO2. They have yet to recover — a permit to emit a metric ton of CO2 now trades at around €5. The main reason is too many allowances. After the financial crisis, falling industrial output coupled with changing environmental policies lowered emissions across Europe, leaving power plants with allowances to spare — further exacerbating the problem of excess allowances. Joining the CDM added more emissions credits to a system that was already awash with them.

The European Commission has introduced reforms to reduce the glut. In 2011, it barred certain CDM offset credits, starting in 2014. The most significant prohibition was on credits for destroying the potent greenhouse gas HFC-23, a by-product in the manufacture of the refrigerant HCFC-22. The CDM had already unwittingly created a perverse incentive, as legal scholar Michael Wara pointed out: companies had been generating more HCFC-22 to capture offset credits from destroying HFC-23. Worse, when these credits were banned, they flooded the market as firms rushed to sell them before they became worthless. Businesses banked their other allowances, lowering demand further.

Despite this and other steps, European carbon prices remain low and oversupply is unsolved. In February, the European Parliament voted to accelerate the tightening of the cap on emissions, from the current annual decrease rate of 1.74% per year, to 2.2%, but that won’t start until 2021.

California is also experiencing low demand for credits, and low carbon prices as a result. The scheme launched in 2013 as part of the state’s suite of policies for achieving its ambitious emissions-reduction goals. It was an open regulatory system from the start, and interacted with other climate-related policies. Prices are higher than in Europe because there is a price floor below which carbon allowances cannot be sold (currently around $13 per ton). In the most recent auction, in February, only 18% of available allowances were sold.

In 2014, California and Quebec began pooling their allowances through joint quarterly auctions, but this has only spread California’s carbon-trading woes to Canada. Nevertheless, Ontario’s carbon market, launched at the start of 2017, intends to link with that of California and Quebec, although no date has been set. The provinces of Acre in Brazil and Chiapas in Mexico plan to join during or after 2018.

Neither the EU’s nor California’s effort at linking has delivered a strong carbon price. Links only make carbon markets more interdependent, and thus sensitive to changes elsewhere..

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that carbon trading is more a political fix than an effective way to mitigate climate change. Without stringent caps and careful management, cap-and-trade systems have scant effect on net emissions. For example, Californian law allows electricity providers to meet the emissions cap by buying energy from sources outside the state. Instead of buying dirty energy, from, say, a high-emissions Nevada coal plant, providers can swap to cleaner sources (an Oregon natural-gas plant, for instance). Although the Californian utility is emitting less by using energy from a cleaner source, a non-Californian utility will still buy the dirty energy. The result of this ‘resource shuffling’ is lower emissions in California but no net change in US or global emissions, as energy economist and legal scholar Danny Cullenward has pointed out.

A Higher Price

A central carbon bank could solve many of these problems, in part by adjusting the supply of allowances to prevent price volatility. But creating a new international institution — and insulating it from political influence — is a tall order. In the meantime, I offer three suggestions.

- Policymakers should limit links to other markets. China’s national market will be the largest in existence when it launches this year. It should postpone linkages to other cap-and-trade systems. Policymakers should also reject offsets from other jurisdictions. The EU-ETS should expand its list of barred credits to include more, or even all, CDM projects.

- Policies should be designed to avoid over-allocation and ensure rising prices. Regulators should establish institutions to insulate the allocation process from political pressure. The forthcoming EU-ETS Market Stability Reserve could be a promising start in protecting the European cap-and-trade program from member-state influence.

- Policymakers should eliminate loopholes that limit the environmental effectiveness of cap and trade. For example, the “resource shuffling” noted above was barred in California’s initial regulations, but was later allowed in under pressure from utility companies. The result has been outsourcing of emissions rather than net reductions.

The worst possible outcome of linked markets is a set of policies that appear to address climate change but allow emissions to continue to rise.

Jessica F. Green is an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Studies, New York University, New York City, USA. e-mail: