Yesterday I biked to Grand Central Station and boarded a commuter train to the Hudson River village of Tarrytown to participate in a forum on carbon taxes. (For readers not from the area, Westchester is the suburban county immediately north of New York City.) My co-panelists were climate organizer Iona Lutey and economist Sara Hsu.

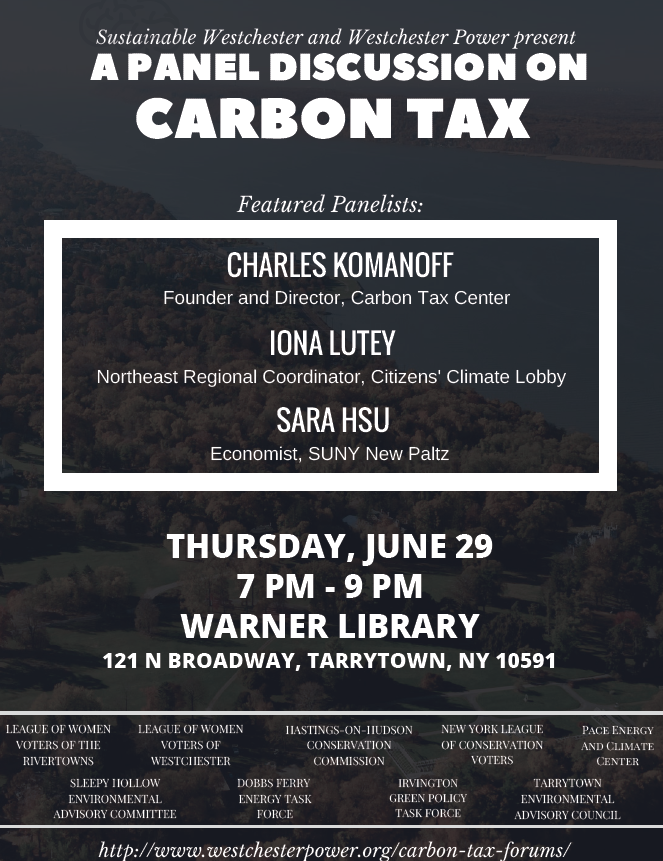

Flyer for the first of three forums in Westchester County (NY) this summer. See text at end for July 19 and 26 details.

Sara, a professor of economics at the State University of New York, outlined her research and legislative advocacy for a NY State carbon tax, while Iona delivered Citizens’ Climate Lobby’s hopeful message that persistent but collegial citizen engagement can build political will for the group’s “carbon fee and dividend” proposal, even among Republicans. I had a subtle pitch: emissions are falling in the U.S. and flattening in China without the benefit of carbon emissions pricing, yet carbon taxing is essential to accelerate and broaden progress.

I usually make that point with modeling results, but last night I brought something new: a Powerpoint page (shown below) listing a dozen complementary pathways for reducing use of fossil fuels that need the price signal from a carbon tax to. (Download my PPT here.)

All three presentations seemed to hit home with our audience of 40 or so folks, most of whom haled from nearby towns and villages. (The local paper Hudson Independent has a fine summary.) The Q&A was unusually lively. A resident of nearby Croton-on-Hudson had perhaps the most provocative question of all: why trade away the right to sue the fossil fuel purveyors and extractors, as the Climate Leadership Council is proposing in its Republican-branded carbon tax deal, when successful litigation could deliver a double-barreled victory: bankrupting the carbon barons while providing financing for the energy transition to efficiency and renewables?

The question was in response to the support I voiced for the Climate Leadership Council’s deal in my talk and in my previous post here. My primary answer then and now was that there seems to be little chance that oil, coal and gas companies could ever be made to pay more than token amounts for the ruin their products cause. But the question deserves further thought, which I kicked off this morning with this thought experiment:

What if we took all U.S. CO2 from burning fossil fuels over the past century and split “responsibility” for it 50-50, with half of the costs written off as the “fault” of consumers (who weren’t entirely innocent buyers and burners of all that gasoline and fuel-based electricity), and the other half charged to the fossil fuel producers? What magnitude of damages and reparations would that entail?

A slide from my presentation in Tarrytown yesterday.

A molecule of carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere for roughly a century, so we need to consider 100 years of fossil fuel combustion. The historical magnitude of U.S. CO2 is more or less known, but for this exploratory calculation we might rough-estimate the century’s total as 60 years worth of last year’s emissions of roughly 5 billion metric tons. To each metric ton we now apply a $50 “social cost of carbon,” though that’s almost certainly far too low, as I wrote here recently.

With these rough assumptions, the producers’ “debt” is then one-half of 60 years x 5 billion metric tons x $50 per ton, which equals $7.5 trillion. Paying that out as damages over, say 20 years implies an annual charge to the producers of $350-$400 billion. Interestingly, that’s the same as the annual revenue from a $75/ton carbon tax.

Let’s now say, improbably but hypothetically, that Congress enacted, and the courts approved, award of those damages to Americans (setting aside, for now, damage claims from the other 7 billion of the world’s people). Where would the money come from? It seems implausible that it could be clawed back from shareholders of the fossil fuel corporations. Could it come from raising the prices of the fuels over the next several decades, in which case it could function as a de facto carbon tax? But if so, why not just enact a carbon tax in the first place?

As you can see, I’m trying to wrestle with this issue. I welcome comments and suggestions.

Meanwhile, Sustainable Westchester and Westchester Power, organizers of last night’s forum, are hosting two more evening panels: Wednesday, July 19 in New Rochelle, and Wednesday, July 26 in Bedford Hills. Details here. I’ll be speaking at both.

Drew Keeling says

Thanks for the interesting “back of envelope” carbon tax versus carbon damages comparison, which is both useful and timely.

There is a basic logic to the “double-barreled” approach (pursuing both), namely that national carbon taxes would shape future carbon emissions, while a lawsuit against fossil fuel producers would presumably be based on past damages.

“Why not just enact a carbon tax?” nonetheless does make sense, because it (unlike lawsuits for past damages) is a POLITICALLY achievable goal. The outcome of lawsuits, in contrast, is decided by courts of law based on judgments about the legality of past actions. It is not possible to politically organize a time machine to change the past, nor is it possible in the USA (without violating the Constitutional prohibition on ex post facto laws) to extract punishment retroactively for actions that were legal at the time.

A national carbon tax could be enacted in America as early as the beginning of 2019, as a result of essentially political means. 100% of the House of Representatives will be elected in November 2018. Successful pro-carbon tax candidacies in a majority of districts would suffice to enable passage in that chamber (plus a majority of the Senate and Presidential signature, or 2/3 of both houses of Congress, being necessary for final enactment).

The likelihood of political success for a national revenue neutral carbon tax is a different issue. As long as the two major political parties have effective control over most of the national legislative process, and as long as both (albeit for different reasons) are defacto against carbon taxes, the likelihood remains small. But, that is something which can be changed through political organizing. All the political organizing in the world, however, is not likely to effect the composition of the US Supreme Court, let alone change legally viable interpretations there, based on past precedents, etc., of past actions by fossil fuel companies, at least not within the next few years.