America is anti-urban. This is not a feeling or a passing fancy but a fact. While the House adheres to the principle of one person-one vote, more or less, the Senate is a horror show of anti-democracy. Thanks to the principle of equal state representation, it gives the three percent of the population that live in the ten smallest states the same number of senators as the 54 percent that live in the ten largest. The Electoral College triples the clout of Wyoming, Vermont, and other under-populated states in presidential elections while Article V — the constitutional clause that says that two-thirds of each house plus three-fourths of the states must approve any amendment — allows thirteen states representing as little as 4.4 percent of the population to wield an absolute constitutional veto. In case you were wondering, this, in a nutshell, is why an eighteenth-century relic like the Second Amendment will never, ever go away.

But because the least populous states are the least urban for the most part, the result is a profound structural bias in favor of acres over people. And since American politics are also fragmented and de-ideologized, the effect is not only to short-change urban interests but to confuse and obscure them so that Americans no longer recognize what those interests really are.

Here are two examples of how US-style structural anti-urbanism plays out. One involves pot. The other involves carbon.

Although you wouldn’t know it, thanks to a near-century of Washington scare tactics, smokeable marijuana is one of the world’s most benign inebriants. As Lynn Zimmer, a sociologist at Queens College, and John P. Morgan, a professor of pharmacology at the City University of New York, showed twenty years ago in “Marijuana Myths, Marijuana Facts,” large-scale studies of users have “generally supported the idea that marijuana was a relatively safe drug — not totally free from potential harm, but unlikely to create serious harm for most individual users or society.” Contrary to anti-drug alarmists, pot does not harm reproduction or fetal development, it does not damage brain cells, and it does not cause “significant reduction in any pulmonary functions,” most likely because regular users consume at most three to five joints per day versus the ten to forty cigarettes consumed by a typical smoker. Marijuana also does not inexorably lead to an “amotivational syndrome,” which is to say stone-style listlessness, according to Zimmer and Morgan, and it is not a “gateway” to harder drugs either.

Although you wouldn’t know it, thanks to a near-century of Washington scare tactics, smokeable marijuana is one of the world’s most benign inebriants. As Lynn Zimmer, a sociologist at Queens College, and John P. Morgan, a professor of pharmacology at the City University of New York, showed twenty years ago in “Marijuana Myths, Marijuana Facts,” large-scale studies of users have “generally supported the idea that marijuana was a relatively safe drug — not totally free from potential harm, but unlikely to create serious harm for most individual users or society.” Contrary to anti-drug alarmists, pot does not harm reproduction or fetal development, it does not damage brain cells, and it does not cause “significant reduction in any pulmonary functions,” most likely because regular users consume at most three to five joints per day versus the ten to forty cigarettes consumed by a typical smoker. Marijuana also does not inexorably lead to an “amotivational syndrome,” which is to say stone-style listlessness, according to Zimmer and Morgan, and it is not a “gateway” to harder drugs either.

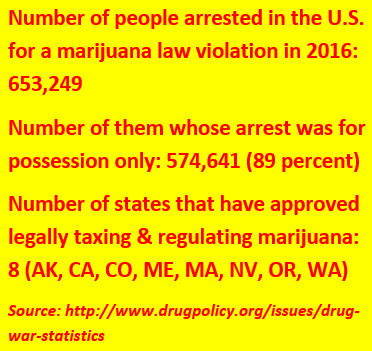

So legalization is an attractive alternative for all those seeking to make America a healthier, happier, and — dare we say it? — mellower place. But it is especially attractive from an urban point of view simply because depressed inner cities are where many of the drug war’s social costs are concentrated. Black users are nearly four times as likely to be arrested as whites according to the ACLU, while poor people in general are disproportionately penalized. In New York City’s twenty wealthiest neighborhoods (average family income: $75,000 per year), the arrest rate in 2014 for marijuana possession was just 39 per 100,000; in its twenty poorest (average family income: $34,000), the arrest rate was 498, nearly thirteen times greater.

Thus, support for marijuana legalization should be strongest among minorities and the poor and the politicians they elect. And it would be if America were more democratic. But given its present anti-urban structure — which, by the way, is worsening as the interior continues to lose ground to burgeoning coastal communities — strange anomalies appear.

One is in New Jersey, where Democratic Governor Phil Murphy was elected last fall on a pro-legalization platform. But since Murphy took office in January, replacing the disgraced Chris Christie, marijuana reform has run into a buzz saw of opposition. The resistance comes not only from skittish suburbanites, but, strikingly, from the state legislature’s black caucus. At a recent public hearing in hard-pressed Jersey City, opposition ran so high that a supporter described it as a case of “reefer madness.”

“It will devastate the African-American community,” a Newark religious leader proclaimed. “It will devastate any chance of our children having a future.” Added an ex-Newark public defender named David Evans: “Is legalization going to improve the spiritual health of the people of New Jersey? I don’t think so.”

NJ State Sen. Ronald L. Rice questions legal marijuana’s impact on Newark and other urban communities. AP Photo by Julio Cortez.

But it would improve spiritual health for the simple reason that nothing raises morale more than the knowledge that one will not spend years in prison for the crime of puffing on a harmless weed. Critics do have half a point in the sense that no social policy is cost-free and that inner cities are justified in assuming that they will once again be saddled with a disproportionate burden. As State Senator Ronald Rice, an ex-Marine and ex-Newark police detective who chairs the NJ legislative black caucus, told The New York Times: “[I]t’s being sold on the backs of black folk and brown people. It’s clear there is big, big money pushing special interests to sell this to our communities.”

All too true. But what critics evidently don’t realize — what an inequitable power structure prevents them from realizing — is that, all things considered, inner-city communities will still be better off if non-punitive policies are adopted and the individual is left alone to decide what substances to ingest and what not to. And that’s true even if marijuana reform is revenue-neutral, that is, if it simply legalizes sale and use without dedicating cannabis tax revenues to communities hollowed out by the drug war and mass incarceration. Even a half-good reform is better than nothing.

And now onto the second issue: carbon. The arguments in favor of carbon taxes are every bit as overwhelming as those in favor of marijuana legalization. They discourage carbon-dioxide emissions that are the prime cause of global warming, they encourage a switch from fossil fuels to sustainable energy sources, and, by de-incentivizing driving, they help thin out the chronic traffic congestion that paralyzes the country’s major metropolitan areas.

But what’s often overlooked is the effect not just on traffic or climate, but on America’s much-abused urban centers. To the degree carbon taxing discourages driving, it encourages a shift to mass transit, which, by its very nature, tends to feed into densely-populated cities. Moreover, mass transit doesn’t just funnel people into such nodes — it funnels economic activity and jobs. To the degree that taxing carbon encourages energy to be used more efficiently, it encourages a switch from cars and trucks to biking, walking, and rail, all of which are more compatible with high urban densities. By altering the incentives, taxing carbon emissions applies the brake to powerful centrifugal forces that have spun employment off into ever more distant exurbs, replacing them with centripetal forces returning them to the old urban cores and central business districtss.

Carbon taxes won’t do this all at once, needless to say, but they will at least start the process moving. This is good news for a lot of people, but especially for urban job seekers who can’t afford a car and can’t pursue job opportunities ever farther out in the suburbs because of racial barriers expressly designed to keep them away. Instead of their going to the jobs, the jobs will go to them.

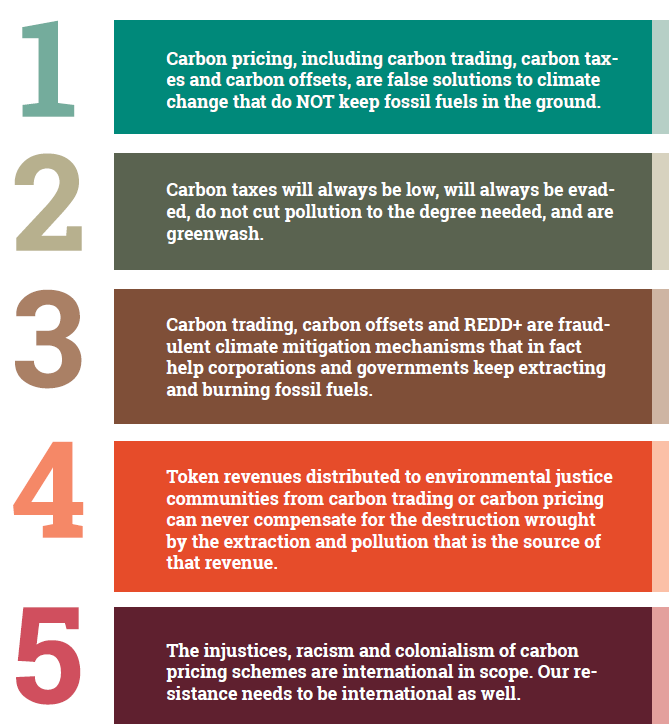

Given all that, one would expect environmental progressives to clamor for ever more carbon taxes — the bigger the better. But anomalies arise yet again. When the state of Washington decided to submit a modest carbon tax to a referendum in 2016, “progressives” led by DC-based Food and Water Watch countered that the tax was regressive, that “people drive because they have to, not because they want to,” and that “[i]ncreasing gasoline prices only means that struggling families will have to cut back on other expenses to fill up their cars at the pump.” Opposition by such “social justice” groups was one reason that the tax, a US first, went down in defeat by a margin of nearly 3 to 2.

From searing words like these (from “Carbon Pricing: A Critical Perspective,” by the Indigenous Environmental Network and the Climate Justice Alliance), one wouldn’t know that carbon taxing can benefit frontline communities disproportionately.

Like critics of marijuana legalization, however, “progressives” had no more than half a point. Boosting gas prices will negatively affect the working poor, which is why any proper carbon tax should include mitigations in the form of reimbursement, which the Washington referendum provided in spades, or promises to invest revenues in job-creating infrastructure projects. But the idea that “people drive because they have to” is nonsense. Driving is not inelastic. As prices rise, motorists cut back on discretionary driving or search for alternate means of going from here to there. The job of progressives is to demand that government provide such means and that it use its economic power to mold development in a way that is more cost-effective for working people, more environmentally benign, and more economically productive. Progressives also need to stop rejecting widespread evidence that “internalizing” climate damage-costs into the prices of coal, oil and gas instills powerful incentives to move off of fossil fuels, even when government investment lags behind.

The present transportation system meanwhile works less well for more and more people. By 2016, the average American was spending a hundred hours more each year in a car than in 1980, the equivalent of two and a half work weeks. Rush-hour speeds are declining according to a study by Texas A&M University, meaning that commuters are spending more time going less far. By 2012, the average car on the road was more than a year older than in 2007 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, while the cost of repairs, upkeep, and replacements was up as well. The duration of an average car loan has risen thirteen percent since 2009 while delinquent loans since 2012 have nearly doubled. The typical motorist is stressed sitting in traffic and stressed when struggling each month to pay off his or her loan.

As bad as this is, conditions are even worse for those who can’t afford a car and must therefore spend hours a day traveling by bus to ever more distant work places and then make their way across dangerous highways when they get back home. People like this are stranded in a hostile, highway-bound wilderness, forced to fork over large amounts of cash for a taxi or Uber whenever they want to go to a supermarket, an emergency room, or church.

The system is no less dysfunctional than America’s endless drug wars. Yet an increasingly undemocratic and anti-urban structure not only prevents Americans from acting effectively to fix it, it prevents them from even thinking about how to address a growing list of problems in a constructive way. Politics have broken down, trench warfare has engulfed Capitol Hill, and the showdown between the intelligence community and the White House grows ever more ominous. Is this how the captain of the Titanic felt when he suddenly noticed a mountain of ice looming before him?

Daniel Lazare, author of “The Frozen Republic: How The Constitution Is Paralyzing Democracy” and “America’s Undeclared War: What’s Killing Our Cities and How We Can Stop It,” among other books, is an occasional contributor to the Carbon Tax Center blog.

Lorna Salzman says

What are black community leaders and activistis doing about handguns and alcohol, which are far more harmful than marijuana

Nathan Hartman says

After reading this blog, inspired by watching one of the most fluent and concise documentaries “Before the Flood” addressing controversial issues such as Carbon Taxes and Global Climate Change, I believe that our economy, civility, and social sectors need to hone upon these topics. Not only has the Trump Train swept assimilate issues under the carpet due to the vast industry for coal and it’s likewise effect on oil prices in global markets, the Senate and big government has neglected to educate the public on how these geopolitical/environmental factors have adversely impacted national affairs. We have a chance to preserve and regenerate directly through education and affirmative action on these specific issues. Thank you for your support and investment towards a cleaner, brigher, and more efficient nation.