Carbon pricing is catching on around the world, but only at “a snail’s pace,” and carbon-pollution prices remain far too low to make much of a dent in emissions, says a new report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Effective Carbon Rates 2018: Pricing Carbon Emissions through Taxes and Emissions Trading reports that the “carbon pricing gap” — the amount that current carbon prices lag an admittedly low benchmark price — shrank from 83% in 2012 to an estimated 76.5% this year. The figures cover 42 countries with advanced economies and account for 80% of all carbon emissions.

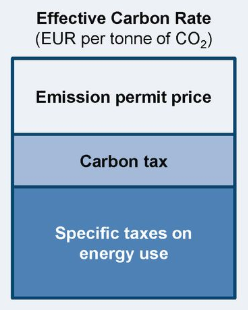

A key pillar of globalism, the OECD grew out of the postwar Marshall Plan and is dominated by three dozen “developed” countries in North America and Europe but also includes Turkey, Chile and Japan. Its “effective carbon rate” is defined as the sum of revenues from three types of policies:

- taxes on specific fuels

- carbon taxes

- prices of tradeable emissions permits

We added the pull quote shown above. The OECD report articulates the economic and geopolitical case for carbon pricing even as it documents the hesitant pace of progress.

The report compares that rate to the revenue that would be raised with economy-wide carbon prices at benchmark levels of 30 or 60 euros per metric ton (about $35/$70US at current exchange rates, or $32/$64 per “short” ton). The report didn’t count the impact of fossil fuel subsidies that lower market prices of carbon fuels, though these tend to be fairly low in the 42 countries studied.

For individual countries, the carbon pricing gap — the distance between actual pricing and the €30/tonne benchmark — ranges from 27% to 100% in 2015, the latest year for which complete individual-country data is available. The US, with a gap of 75%, ranked 31st among the 42 countries studied. Top rankings go to Switzerland (27%), Luxembourg (30%), and Norway (34%).

Russia, at the bottom of the list, has no carbon pricing at all. China ranks 39th, with a 90% shortfall from the €30/tonne benchmark, though the report notes that implementation of nationwide carbon-permit trading in China “could lead to a significant drop in the global carbon pricing gap, to 63% in the early 2020s.”

Schematic from OECD report. The bottom category, specific taxes, is most countries’ primary contributor to the effective carbon rate.

The report is upfront about its benchmark’s limitations. The World Bank–affiliated High Level Commission on Carbon Pricing warned last year that carbon prices must range from $40 to $80US per tonne by 2020 and $50-$100/tonne by 2030 to meet the emission targets of the Paris Climate Agreement. (And remember that those goals are almost universally regarded as too low.) Moreover, the 30 euro benchmark falls below even the bottom of the 2020 range. And advanced economies — which most of the countries studied are — should err toward the high end of that range, according to the Commission, to leave room for developing economies to reap at least some of the fruits of industrialization.

Applying a more realistic 60€/tonne benchmark (about $64US per short ton) casts the pricing shortfall into even sharper relief: under that benchmark the 2015 US gap would be 88%.

Perhaps surprisingly, the largest of the three contributors to OECD’s effective carbon rate is neither explicit carbon taxes nor tradeable carbon emssion permits, but taxes on specific fuels, especially in road transport. European countries, especially, began taxing gasoline and diesel fuel at high rates decades ago, not as a climate measure but to reduce car dependence in urban areas, to help rail and other public transit maintain market share, and to fund social programs. Years later, those taxation policies are now, properly, being recognized for their role in protecting climate as well.

Drew Keeling says

Thank you for this useful metric against which to measure (lack of) progress.

Many future generations are going to ask the question:

WHY didn’t our generation(s) act more responsibly, despite what should have been clear available knowledge of the problems (long-lasting downsides of over-reliance on fossil fuel energy sources, e.g., global climate disruption) and of sensible and available ameliorating responses (e.g., socially responsible carbon pricing)?

Some future descendants will no doubt ask why our late 20th and early 21st century generations did not at least more actively pose that question ourselves.

This is something we ourselves could and should at least ponder now:

Why?

Key components of answers, and/or hints at them, can be found in the back pages of this very website.

Keep up the good work!