The Democrats flipped the House all right, turning a 41-vote Republican margin into a 34-vote Democratic edge. Intra-party debate is already under way over how to make productive use of the next two years while the rest of the government remains in Republican hands. In the climate space, there’s a hot (though hardly new) progressive idea: a Green New Deal.

Last week, climate activists led by the Sunrise Movement took the idea to (literally) the halls of Congress, demonstrating outside the office of presumptive speaker Nancy Pelosi. They were joined by the newly elected and already iconic progressive star Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who has drafted an ambitious resolution calling for a Select House Committee on a Green New Deal.

The committee would be charged with developing:

a detailed national, industrial, economic mobilization plan . . . for the transition of the United States economy to become carbon neutral and to significantly draw down and capture greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and oceans and to promote economic and environmental justice and equality.

Pelosi, for her part, immediately announced her intention to reconstitute the Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming, which she had created as speaker in 2007-2011. For the full context, we recommend two posts by Dave Roberts of Vox that bracketed the Capitol Hill protest. The day before, he discussed the Democrats’ prospects in a divided Congress. The day after, he reported on how the protest played out, including Ocasio-Cortez’s role.

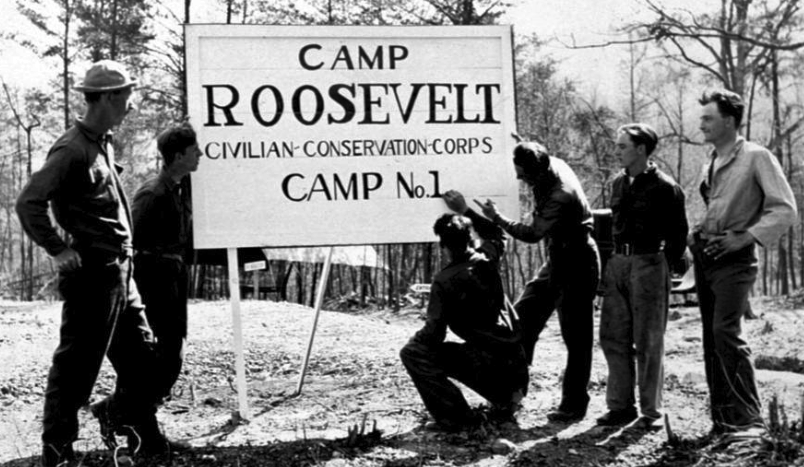

A Green New Deal workforce will be more urban, female and diverse than its honorable forebear.

The Green New Deal is still little more than a concept. The phrase has been a favorite of New York Times columnist Tom Friedman at least since 2007 and was part of presidential candidate Barack Obama’s platform in 2008. (Grist published a nice history last summer.) Needless to say, Friedman’s Green New Deal and Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal aren’t close to the same thing. The devil will be in the many details to be worked out in that select committee.

Ocasio-Cortez’s resolution calls for:

- 100% renewable power generation

- a national energy-efficient smart grid

- upgrading the energy efficiency of all buildings

- decarbonizing transportation, manufacturing, agriculture and other sectors

- massive investment in capture of greenhouse gases

- making “green” technology a major U.S. export

Her proposal also includes a number of broader but arguably connected goals, including retraining, a job guarantee, a living wage, environmental justice, and greater economic equality.

There’s also a concurrent debate over strategy. The Democrats’ initial aim on climate has been to write the Clean Power Plan and rising CAFE standards — both under threat by the Trump Administration — into statutory form and force the Republican Senate (and/or Trump himself) to go on record opposing those popular measures. Sunrise and other progressive groups are demanding much more: development of a fleshed-out program to be enacted as soon as Democrats re-establish control of Congress and the White House.

What will a Green New Deal mean for a carbon tax? For one thing, any program to move U.S. society and economy quickly off fossil fuels will cost a lot of money; a carbon tax — which has climate benefits irrespective of how the revenue is used — is a logical source of funding. In particular, a robust carbon tax makes everything we want to do on climate easier — reducing the need for renewable subsidies, shortening the payback period for clean energy investments, etc.

Furthermore, as the most recent IPCC report explained, the planet’s back is now against the wall, and we need to do everything we can as fast as we can to limit the most damaging consequences of climate change. Clean-energy subsidies and efficiency standards by themselves won’t be sufficient. Leaving carbon pricing on the table would be a dereliction of duty.

Finally, U.S. action, necessary as it is, won’t be enough. A carbon tax, combined with border adjustments against countries without similar policies, can help move the entire globe in the right direction.

An important caution is that the right question needs to be asked when deciding how high a carbon tax should be. The question is not, How much money do we need?, but How much emissions reduction do we want to achieve through pricing? And for the sake of equity, a good portion of carbon tax revenues should be devoted to dividends or tax offsets that buffer households, and especially lower-income ones, against the impact of higher energy prices.

The new push for a Green New Deal represents a serious movement within which a carbon tax can and should play a key role. Nothing will happen as long as Republicans sit atop most of the federal government, of course. But the Green New Deal offers the kind of ambitious platform that carbon tax advocates have been calling for all along.

Mark Tabbert says

The Carbon Tax Center never fails to pour cold water on their push for carbon pricing. In this very good op-ed they do it in a single line. “Nothing will happen as long as Republicans sit atop most of the federal government”. This thinking doesn’t inspire and it is wrong. I believe there are enough Republicans in Congress who know we need action on climate change and who will work with the Democrats especially if the Democrats make climate change a bridge issue and stop using it as yet one more wedge issue. If the Democrats would become the golden rule party and change the dynamics in Congress there may be enough votes to override a Trump veto.

Drew Keeling says

It is good news that newly elected Congressional Democrats are taking a stance on something significant, so thanks for this timely report and analysis.

Whether this stance will amount to much is questionable, however.

During the crucial years of the New Deal, e.g. 1933-38, Democrats had control of the White House and well over 2/3 of each chamber of Congress. Democrats today have more than a little ways to go if they want recreate something like FDR’s New Deal era for the 2020s.

Pelosi, Schumer, Biden, etc. are not FDRs. The last two times Democrats had the White House and all of Congress were in 1993-94, when Clinton punted on green energy and climate change once his BTU tax was defeated in the first six months of his first term, and likewise 2009-10 with Obama and the unsuccessful cap and trade attempt of June 2009.

It would be nice if a “Green New Deal” could be installed and paid for by carbon tax revenues, but that still seems like a long shot from where we are now. Even a Green New Deal INSTEAD of a carbon tax (as, in a weaker form, in the 2016 Democratic platform) looks unlikely until the next major recession hits (which under current circumstances could, however, come sooner than people expect). Standard Democratic operating procedure of the last twenty five years nonetheless points more towards rhetoric, posturing, and tokenism than towards substantive reform. The Democratic Party in Washington State did not manage to collect a majority of voters for either of two modest carbon tax initiatives, over past two years. This in a state where for the past 20 years both US Senators and two thirds of its House of Reps delegation have been Democrats. We cannot (yet) anticipate better success at a national level.

“No nation,” presidential candidate John F. Kennedy noted in 1960, “is at its best except under great challenge…it is only when the iron is hot that it can be molded.” Unfortunately, for any contemporary would-be emulators, the challenges America faced in JFK’s presidency were not primarily challenges resulting from American blunders.

I think the chances for progress on decarbonizing the economy would improve if we could maintain a sharp focus on the (short- and long term) reasons why such progress has so far been difficult to achieve on a substantive scale.