On Wednesday, Rep. Ted Deutch (D-FL) and a small bipartisan group of cosponsors introduced the strongest carbon pricing bill dropped into the Congressional hopper in years. H.R. 7173 closely follows the fee-and-dividend proposal long championed by Citizens’ Climate Lobby, employing not just the dividend template but the robust price trajectory.

The Deutch bill sets an initial tax rate of $15/metric ton, rising by $10/tonne annually thereafter. The increase rate would rise to $15/tonne if annual emissions targets are not met. All of the revenue, net of expenses, would go toward equalized dividends to all American households, based on household size, making the overall proposal revenue-neutral.

H.R. 7173 includes a border adjustment for both imports and exports, to protect the competitiveness of American manufacturing. And it restricts the government’s powers to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, at least for their impact on global warming — a limitation that may be more symbolic than substantive, given the modest emissions impact of President Obama’s signature Clean Power Plan, especially when compared to likely reductions from the new bill’s steep price trajectory.

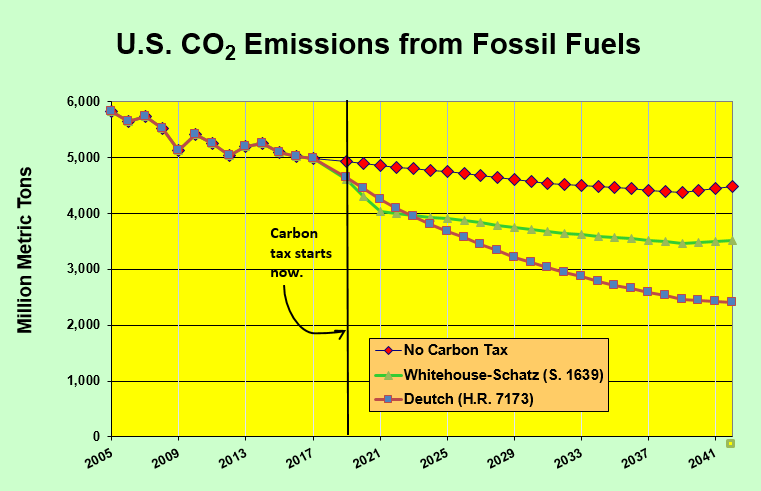

The Deutch fee-and-dividend bill would surpass the most aggressive recent Democratic carbon tax after five years and would have twice the impact soon after.

The buzz thus far has focused on the bill’s initial cosponsors, two of whom are Republicans: Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA) and Francis Rooney (R-FL). This is not their first trip to the rodeo. Both also cosponsored a much weaker carbon tax bill introduced in July by Carlos Curbelo, who lost his bid for reelection. A third Republican, Dave Trott (R-MI), has since signed on. The two Democratic cosponsors are Charlie Crist (D-FL) and John Delaney (D-MD).

It’s important not to make too much of the bipartisanship on display here. Fitzpatrick, Rooney, and Trott represent an underwhelming 1.5% of the incoming Republican caucus in the House. More particularly, they constitute a mere one-seventh of the surviving Republican members of the all-too-quiescent Climate Solutions Caucus, which is losing most of its GOP contingent to defeat or retirement. Deutch and Curbelo were the founding chairs of the Caucus.

The larger substantive story here is the long-term impact of the Deutch proposal. His $15/tonne starting tax rate is lower than other bills introduced in this session, which range from $24/tonne (Curbelo) to $49/tonne (two Democratic proposals, S. 1639 and H.R. 4209). But the rates in those bills would generally rise by only 2% above inflation annually. Deutch’s proposal, though it starts from a lower base, would outstrip them in impact after just five years, with the differential only widening over time.

According to the Carbon Tax Center spreadsheet model, Deutch’s bill would reduce U.S. CO2 emissions below 2017 levels by 35% in a decade. The best of the Democratic proposals would see a smaller reduction of 25%.

The chances of any carbon tax bill passing in the next Congressional session are close to nil. It is hard to imagine such a proposal getting a floor vote in a chamber led by Sen. Mitchell McConnell (R-Coal Country, aka Kentucky). Even if it did, the veto pen of Donald Trump awaits. Nevertheless, the next two years will allow a debate within the Democratic Party over what its position will be on climate change in the 2020 campaign and, assuming that election goes well for them, in the 2021-22 Congressional session.

The Deutch bill is clearly a contender in that debate. And the more Republican cosponsors Deutch and CCL can recruit this session, the more likely it can become that a robust carbon tax, with revenues going back to American households, will be at least part of the answer.

The other major contender for a Democratic climate program right now is the as-yet-unspecified Green New Deal with major green infrastructure investments possibly funded by a carbon tax. Interestingly, the carbon tax bill with the most support in the House at present, with 21 cosponsors, would also devote most of the revenue to infrastructure, though not specifically green infrastructure. That’s H.R. 4209, the America Wins Act sponsored by longtime carbon tax champion Rep. John Larson (D-CT).

The important thing for carbon tax advocates to remember is that the best bill is the one that can pass. So may the best bill win.

Drew Keeling says

Given that “the chances of any carbon tax bill passing in the next Congressional session are close to nil,” then “the best bill is the one that can pass”…26 (at least!) months from now! In the current wrecking ball mode of US politics, 26 months is a long time…to -for instance- compare, point by point, what might remain two leading legislative possibilities, as discussed here: HR 7173 versus HR 4209.

On the further assumption that the dominant political offerings in Nov. 2020 will be something like a quasi-Trump elephant and a neo-Clinton/Obama donkey, such potentially improved chances for national carbon taxation two years hence would appear to be contingent upon a donkey sweep of both houses of Congress and the White House in the next general election.

Ergo, it would seem to make sense in the meantime to look into how to protect HR 4209, or some later ‘New Green Deal’ (or whatever other specific proposal might emerge over the next 2 years as the leading “contender for a Democratic climate program”), from overburdening with special interest pork, and to consider ways of solidifying and strengthening any (potential) carbon tax element within such a bill.

Such crystal ball gazing aside, this is an excellent and welcome synopsis of a timely new development.

Mark Tabbert says

If “The better Democratic proposal would see a smaller reduction of 25%.” why is it the better bill? I love that you know the carbon tax is the way to go but your predictions aren’t reliable. You sell the future short and under represent human potential. You should be looking for how to promote the new bill and helping build public awareness.

Bob Narus says

It’s not better than the Deutch bill. It’s better than any of the bills with only Democratic support (and much better than the Curbelo bill). I’ve tweaked the wording to clarify. Sorry for the confusion.

Bruce Hagen says

I remember in the mid-1970s when the experts said we would need a nuclear power plant every 5 miles along the California coast to meet the demand for electricity. Instead, we chose a different course and pursued it with great vigor. We flattened demand through efficiency and gradually replaced fossil power with clean power.

I remember, not so many years ago, when getting Republicans to even acknowledge climate, much less support a strong price on carbon, was impossible. Citizens’ Climate Lobby built a national movement to challenge that, and with exponential growth of membership and citizen lobbying has begun to bend the curve, to what you see in this bill.

With support from the increasingly alarmed and climate-engaged business community, and recurring slaps from climate-aggravated natural disasters, we can bend the political political curve around to a veto-proof majority in both Houses. And bend the emissions curve down in time to save the world we love. Why not try? Contact http://www.BusinessClimateLeaders.org.

“Trend is not destiny.”