Were the midterms “pretty good for the climate-concerned,” as The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer said in his election post-mortem? It would seem so, with the 40-seat “blue wave” ushering in Democratic control of the House and an opportunity to restore climate policy and facts to the political agenda. But for carbon taxes in particular? Maybe not so much.

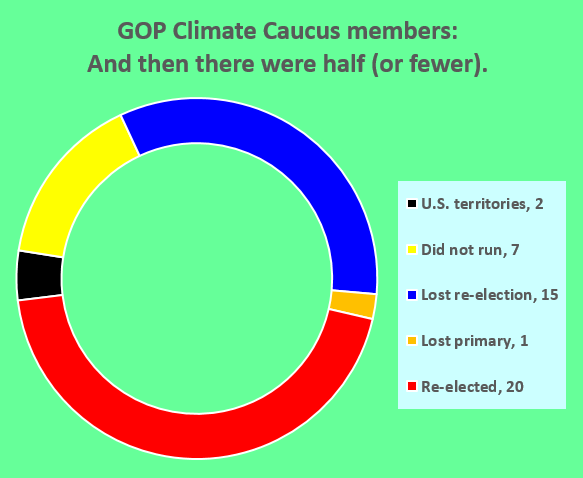

Two contrasting carbon-tax varieties — “revenue-neutral” and “just transition” — were dealt serious beat-downs on Nov. 6. As CTC director Charles Komanoff reported in this space last month, only 20 of the 43 current Republican members of the Climate Solutions Caucus will be returning to Congress next month, an obliteration that dimmed prospects for bipartisan, “fee and dividend” carbon tax legislation. Among the fallen: Caucus-founder Carlos Curbelo (R-FL-25), who lost two percentage points to newcomer Debbie Mucarsel-Powell.

If this chart looks familiar, it’s because we’ve run it several times — that’s how startling it is.

Evidently, the mild climate concern expressed by the vanquished Republicans couldn’t inoculate them from voters determined to put Democrats in charge of the House. In Meyer’s telling, the Climate Solutions Caucus may simply have been inherently unstable. Republicans have to be at least somewhat centrist to want to join the caucus, but the purple districts that might elect centrist Republicans are going to be less secure for Republicans than hard-right districts.

Confounding the obituaries, or perhaps as a last hurrah, the Caucus introduced its first meaningful carbon tax bill in November. As previously reported here, the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act of 2018 (H.R. 7173), co-sponsored by Reps. Ted Deutch (D-FL-22), Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA-08), Francis Rooney (R-FL-19), Charlie Crist (D-FL-13) and John Delaney (D-MD-06)), would set an initial tax rate of $15/metric ton, rising briskly by at least $10/tonne annually thereafter. Several weeks later, retiring Sen. Jeff Flake (R-AZ) and returning Sen. Chris Coons (D-DE) introduced an identical bill in the Senate.

At the same time, the similarly aligned Climate Leadership Council is rumored to be building a bipartisan push for its $40/ton “carbon dividend” bill sometime next year. So it may be too early to count out team revenue-neutral.

On the other end of the carbon tax advocacy spectrum, Washington state’s “just-transition”-oriented Initiative 1631, which would have funded a suite of measures for renewable energy, forest protection and worker transition, went down to defeat by a resounding 56%-44%. As a laboratory of democracy, Washington has now performed yeoman service for carbon tax watchers for three years running: the revenue-neutral Initiative 732 was defeated by an even wider margin (59-41) in 2016, and a legislative carbon tax earmarked to fund public schools failed in 2017.

Big Oil’s $30 million helped sink WA state’s I-1631, but they had allies: editorial boards across the state.

Clearly, no carbon tax faction has yet earned any bragging rights. As reported here, I-1631 had widespread backing from environmental, civil rights and labor organizations, as well as heavy hitters such as Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, Bill Gates and Michael Bloomberg. No matter, that combination proved no match for massive opposition funding bestowed by mostly out-of-state fossil fuel interests, including $12 million from BP, a Climate Leadership Council founding member.

Nevertheless, the midterms are bound to make the overall political environment far more hospitable to climate concerns, as Meyer argues. The question now is how the ascendant Democrats will put their powers to use on climate issues more generally, not just carbon taxes.

Last month, not just the Blue Wave but wildfires, drought and other climate calamities held public attention in much of the U.S. A new generation of activists and incoming Congressmembers began demanding a full-press climate policy agenda that could be enacted once the Trump Administration and its climate-denying allies are put out to pasture.

Hopes were high that House Democrats would use their new position to advance a Green New Deal — the policy rubric prominently advocated by incoming Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and the emerging Sunrise Movement (and that from its earliest conceptions has always included carbon taxation or other carbon pricing). Those hopes receded somewhat last week when their caucus formed a select committee on climate headed by Rep. Kathy Castor (D-FL-14), a 12-year member who hasn’t voiced support for a Green New Deal or any other climate policy idea. (There’s no mention of climate on Castor’s Wikipedia page.)

There also appears to be a growing sense that carbon taxes may belong to an older policy playbook from an earlier, more technocratic era. In that period, a carbon tax could be considered a premier policy tool favored by economists and other well-informed advocates across the political spectrum. Now it may need to take its place as one of an array of options on a newly broadened playing field.

If so, we carbon tax advocates will need to expand our horizons in our search for allies. Rather than “staying in our lane” in the climate change arena, we may need to join a broader discussion that includes issues of tax fairness, efficiency and income inequality. A New Yorker magazine profile of the Sunrise Movement this week notes that “like other activist movements of their generation, they see their cause as inseparable from the broader issues of economic and social inequality.”

Rather than just check the boxes on those issues — as carbon tax organizers did dutifully in both the 2016 and 2018 Washington state initiatives — in the new emergent period of progressive ascendancy we may need to commit our energies to these issues as fully as we do for carbon taxes.

Indeed, it may have been precisely the failure to consider the broader social equity context that doomed France’s recent fossil fuel surcharge at the hands of the Yellow Vests — many of whom express climate concern and engagement but reject being made to bear the brunt of wonky policy measures while their economic betters glide by.

Indeed, it may have been precisely the failure to consider the broader social equity context that doomed France’s recent fossil fuel surcharge at the hands of the Yellow Vests — many of whom express climate concern and engagement but reject being made to bear the brunt of wonky policy measures while their economic betters glide by.

It’s a conundrum as old as environmental policy itself — to do its environmental work, a policy has to work economically but be accepted politically. By making common cause with advocates of economic fairness, as embodied in the Green New Deal movement, we carbon tax proponents may ultimately win a more secure position for carbon taxation than we have done to date.

Such a discussion needs to go beyond the polarized internecine debate among carbon tax proponents over whether such a tax should be revenue-neutral or used to fund new initiatives. It will need to extend into considerations of how the tax functions, whom it impacts as compared to other taxes already in use, and the many ways our society raises revenue for public purposes.

In other words, carbon tax advocacy may have to embody a sweeping re-consideration of current tax and fiscal policies, including an examination of whose interests those policies serve.

Andrew Ratzkin, an attorney and co-chair of the Hastings-on-Hudson Conservation Commission in New York’s Westchester County, is author of the report, Case for a New York Carbon Tax.

Drew Keeling says

A call for widening carbon tax advocacy is welcome, but the devil is in the details of how such widening might occur. There are potential downsides as well as potential upsides.

The recent experience of French president Macron is almost a textbook case for how not to proceed. Recent lessons from Washington State also bear heeding, however. While better strategized than France’s attempts, Washington’s initiatives (whose engineers deserve praise for at least getting carbon pricing on statewide ballots, unlike most other states) also contained flaws. The 2016 and 2018 measures both “embodied” concerns about “broader social equity,” yet failed to win election majorities.

Keep in mind how a pure carbon tax is in and of itself inherently fair. Apart from disadvantaging carbon fuels (by a fractional redress of the massive disadvantages those fuels have imposed for centuries already and will for millennia to come) it does not pick winners or losers. Furthermore, nearly everyone participates in helping to better protect the common global climate. The consumer whose local goods become slightly cheaper due to lower transport costs, the utility incentivized to switch from coal to less carbon-intensive natural gas, the commuter realizing that biking or public transit is cheaper than using a car, developers of more efficient batteries and less toxic solar panels: all are helped by carbon taxes to make positive changes benefitting society and future generations.

The best way to incorporate concerns for fiscal viability and “economic and social inequality,” and to succeed in actually enacting carbon taxes, is probably to keep them as simple as possible (100% refunded, 100% as annual checks to lower and lower-middle income brackets), while redoubling efforts to educate the public and rebut disinformation coming not only from fossil fuel interests, but also from pseudo-activist mainly-pro-environment-in-name organizations, pork-barrel-oriented establishment politicians, and hidden agendas of deregulation. That last threat is particularly keen because it has infused some of the most articulate and well-funded of recent carbon tax advocacy. Furthermore, achieving substantive reduction of CO2 emissions will take more than higher carbon pricing: we also need increased, not decreased, public investment in mass transit, sustainable land-use, energy conservation, non-carbon fuels and climate adaptation. But “Greens” should be pushed to finally halt futile, rote feel-good marches, and instead properly and effectively organize behind direct, tangible and substantive legislative measures, not seek to shunt them, like millstones, onto proposals for otherwise simple, clear and fair carbon taxes.

Eric Haulenbeek says

“Americans in record numbers now regard climate change not as an abstract possibility but a feature of the here-and-now, according to the latest polling by the highly regarded Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication.”

This quote from the above article is highly misleading at best. The available data is simply not quantifiable! We’re not all drinking the kool-aid, and thankfully so!