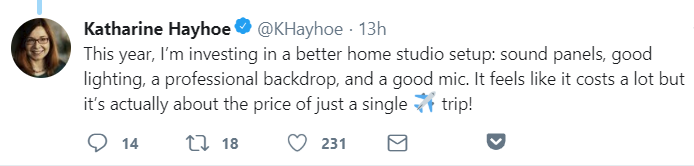

Texas Tech physicist Katherine Hayhoe is investing in a home studio. How do I know? She tweeted about it last night:

Why should we care? Because the professor’s studio upgrade is a microcosm of what a carbon tax — and only a carbon tax — can do for climate.

Some context: Prof. Hayhoe is a renowned voice for climate sanity. At Texas Tech, in Lubbock, she teaches atmospheric science and political science — a potent combination tailored to her dual repertoire of climate physics and climate communications.

These days Hayhoe is inundated with speaking requests, to the point that compelled her to face the tie between her air travel and greenhouse gas levels. Thus the studio upgrade. Now, she tweeted last night, “When I receive a speaking invite, my first question is: could I do a low-carbon video talk? Thanks to peoples’ willingness to give new-fangled tech a try, I now give about 3/4 of my talks this way!” [Click here for Prof. Hayhoe’s complete Twitter thread on the matter.]

Air travel is often trotted out as evidence that climate change is unstoppable — and not without reason. It’s already five percent of U.S. CO2 emissions (some put its climate impact higher, due to flying’s unique atmospheric interactions), a share that is rising, as befits air travel’s “luxury-good” status as an activity that rises faster than incomes. Schemes for lower-carbon propulsion systems, from biofuels or electric motors to hydrogen or high-tech dirigibles, are mostly still at the drawing boards. Packing more passengers into fewer and smaller seats is probably nearing its limit (though perhaps steeper baggage fees will push down per-passenger emissions a bit further).

At least for the immediately foreseeable future, the primary antidote to air travel’s escalating emissions must be to fly less. A carbon tax can bend flying’s demand curve downward, but alternatives like teleconferencing must be part of the process. The better the technology — in ease of use (on both ends), clarity and capability — the more people who will follow in Prof. Hayhoe’s footsteps. Before long, virtual presenting and meeting could grow from quirky to normal. Societal norms will reset, perhaps to the point where jetting to and fro will seem as odd as turning down a trip due to carbon appears today.

Three stages of air travel: physical / digital / something just beyond the horizon.

There are two strands here. One, just noted, is about resetting societal defaults: passing on your second cousin’s third wedding out in Reno not just because the carbon tax has made the trip costlier but because the reflexive, “Nothing could keep me away” has become “This time I’m going to pass” as society has adapted to higher ticket prices (and, perhaps, flying has lost some of its prestige).

The other is about innovation. To stick with our air travel example, ways to participate without physically showing up will inevitably grow more feasible and tantalizing as the carbon tax drives demand toward that direction. Some of the adaptive innovation will be along known paths like teleconferencing, but some will doubtless be along paths few of us can imagine — save for the innovators awaiting the market opportunity.

This stuff won’t be won by regulations, standards or subsidies, but it’s central to slashing emissions, in my opinion. It’s the reason that throughout 2019, as climate progressives brainstorm and settle on the elements of a Green New Deal, CTC will be fighting to ensure that robust carbon taxing is one of them: not simply to generate revenue to pay for green infrastructure but to incentivize the million and one innovations that, even if we can’t yet spell them out, will be key to crushing the structures of demand that still have us hooked on carbon fuels.

Drew Keeling says

Professor Hayhoe’s well-informed and positive suggestions are certainly worth paying close attention to.

Another way to reduce air travel would be to restore America’s passenger rail network to something closer to what most other developed countries have. To be effective, such a project would have to be national, or at least regional, and long term: a good fit as part of a “Green New Deal.”