Editor’s note: On May 31, energy-climate blogger David Roberts posted How California became far more energy-efficient than the rest of the country, a gorgeous distillation of our report, “California Stars.” Roberts’ post explains the policy dynamics underlying our report’s quantitative findings and shows how California has made energy efficiency and renewables the focal point of the state’s economy. His post also makes clear how far all 50 states still have to go while placing “California Stars” in the national political context.

Yesterday the Natural Resources Defense Council released California Stars, my report quantifying and documenting California’s relative success in decarbonizing its economy since the 1970s. I say “relative” because the report’s measure of success involves not one but two relational metrics: carbon reductions relative to economic activity, and California relative to the other 49 states.

I was lead author of this NRDC report documenting how California has surpassed the rest of the U.S. in decoupling economic growth from fossil fuels.

California Stars: Lighting the Way to a Clean Energy Future establishes that from 1975 to 2016, the nation’s largest state reduced the fossil fuel inputs needed to support a constant amount of economic activity 18 percent faster than the rest of the country — a difference with enormous climate consequences. Had the other 49 states matched California’s rate of improvement, the report finds, annual emissions of carbon dioxide nationwide would be lower today by nearly 25 percent, or 1,200 million metric tons of CO2 — the equivalent of all carbon pollution from U.S. passenger vehicles.

There’s more about California Stars further below and in a graceful blog post by long-time NRDC attorney and energy strategist Ralph Cavanagh, who oversaw the report. I was principal author, which may come as a surprise to readers who have followed my career of late. For one thing, the report has nothing to do with carbon taxing. Moreover, a decade ago NRDC and I were on opposite sides of an internecine struggle over carbon pricing, with NRDC backing cap-and-trade and me, on behalf of the Carbon Tax Center, insisting on straight-up carbon taxes. More recently, in 2015, in a blog post, What an Energy-Efficiency Hero Gets Wrong about Carbon Taxes, I went to considerable lengths to counter criticisms from an NRDC energy-efficiency superstar that carbon taxing was too blunt an instrument to do much good in cutting down emissions.

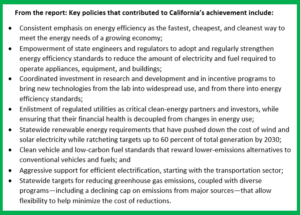

All the same, for over 40 years it has been abundantly clear, even from my East Coast perch, that even without a carbon tax, California’s government has steered its economy more assertively toward energy efficiency and renewable energy than has any other U.S. state. (California does have a modest cap-and-trade program.)

Through the California Energy Commission, a first-of-a-kind agency legislated in the last year of Gov. Ronald Reagan’s administration and staffed in Gov. Jerry Brown’s first (1974 and 1975, respectively), California established not just the first efficiency standards for major appliances and buildings but a process for continually updating those standards to align with — and further incubate — technological advances by which cooling, heat and light may be furnished with progressively smaller energy inputs. These policies, along with innovations that enabled electric and gas utilities to bankroll customer “end-use” efficiency investments, later spread to most of the other 49 states, greatly amplifying their single-state impacts. But they took root first and, it appears, most deeply in California.

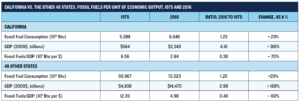

Table 1 from “California Stars” shows that from 1975 to 2016 California reduced its use of fossil fuels per unit of economic output by 70%. For the other 49 states collectively, the reduction was only 60%. That percentage difference equates to 1,200 million excess metric tons of carbon pollution in 2016 alone—a huge missed opportunity for the rest of America.

Needless to say, these policies thrilled me, even from afar. And the policies themselves seemed firmly planted in a statewide culture of energy efficiency and innovation. To be sure, you couldn’t discern that culture in the state’s sprawling subdivisions and freeways, but you could sense it in the passionate conversations about energy that caromed among the policy beehives that were springing up around the state: at the California Energy Commission and the state Department of Natural Resources; at the University of California’s Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory and its Energy Resources Group and at Stanford; at NRDC, which was making efficiency standards sexy not only to other environmentalists but to appliance manufacturers and builders; and at the Environmental Defense Fund, whose pathbreaking analyses were suggesting that investing in efficiency and renewables could make utilities financially stronger.

The font of this activity was Gov. Brown. Whether or not he grasped all of the intricacies — and he probably did — Brown’s personal asceticism and hippie-ish disdain for standard modes of consumption (at least in his first go-round as governor) seemed to furnish the cultural DNA for California’s quiet but consequential energy-policy revolution. This was palpable during my three working trips to the state during Brown’s first term: in 1976 when I campaigned around the state for a ballot measure limiting new reactors; in 1977 when I testified for EDF and NRDC in nuclear power siting cases in San Diego and San Francisco; and in 1978 when I spent a month in Los Angeles with the PhD economist Vince Taylor, workshopping my analyses of cost escalation in nuclear power.

Within a year, that work would catapult me to national prominence, when the Three Mile Island reactor outside Harrisburg, PA melted down and I, providentially, had the computer printouts (regression analyses of the relentlessly rising costs to build nuclear plants throughout the 1970s) that answered the question on the lips of seemingly every energy-journalist in America: what would the TMI accident do to nuclear power economics? Almost overnight, my energy-policy work narrowed to a single-minded focus on nuclear power costs — which ended only when I took up urban-bicycling advocacy near the end of the 1980s.

Within a year, that work would catapult me to national prominence, when the Three Mile Island reactor outside Harrisburg, PA melted down and I, providentially, had the computer printouts (regression analyses of the relentlessly rising costs to build nuclear plants throughout the 1970s) that answered the question on the lips of seemingly every energy-journalist in America: what would the TMI accident do to nuclear power economics? Almost overnight, my energy-policy work narrowed to a single-minded focus on nuclear power costs — which ended only when I took up urban-bicycling advocacy near the end of the 1980s.

By the early eighties, then, I had to give up my close watch on California’s energy efficiency progress. Last September, however, with Gov. Brown’s fourth and final term drawing to a close and with climate concern skyrocketing in the U.S., the time seemed right to determine how far California had actually gotten off fossil fuels since the start of that quiet revolution in energy governance in the seventies. CTC intern (and U-Chicago rising sophomore) Rohan Kremer Guha and I dug up California-specific fossil fuel and GDP data and placed it alongside data for the U.S. as a whole, which led to a preliminary version of the table above.

In a nutshell, we found that from 1975 (the approximate start date of that revolution) to 2016 (the most recent year with consistent data):

- California’s use of fossil fuels increased by 23 percent, a bit more than the rate for the rest of the U.S. (20 percent)

- During that same period, California’s economy more than quadrupled in size, far surpassing the other 49 states’ tripling

- Adjusting the first figures by the second, California reduced its use of fossil fuels per unit of GDP by 70 percent; for the rest of the U.S., the reduction rate was 60 percent

The last bullet point led directly to the startling finding reported at the top of this post: Had the other 49 states reduced fossil fuel use relative to economic activity at the same pace as California, nationwide carbon emissions would have been lower in 2016 by 1,200 million metric tons, or 24 percent.

Proof indeed, not just of California’s leadership but of the rest of the country’s sluggishness . . . and of the consequences of the gap between the two. Because of that sluggishness, the U.S. missed a chance to eliminate carbon pollution equivalent to CO2 emissions from all 200 million passenger cars and (light) trucks in the country. I pitched a report built on this analysis to our friends at NRDC, and our collaboration produced this report.

I’ll have more to say soon, not just on the report itself but on what it says about Jerry Brown’s climate record. You can download the report (pdf) directly from NRDC’s Web site and comment on it here via the link just below the headline near the top of this post.

James Handley says

Supply side is completely different story: “Governor Brown and California’s climate policies have not only failed to reduce dirty crude production but have actually incentivized oil production overall. From subsidizing oil and gas development to weak regulation, California has rolled out the red carpet for oil companies.” https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/climate_law_institute/energy_and_global_warming/pdfs/Oil_Stain.pdf

Charles Komanoff says

True. But so what, from a climate standpoint? Any holdback in Calif oil/gas extraction, while obviously welcome from a local health/safety/toxicity standpoint, would have to be made up by increased extraction elsewhere. Trying to solve climate by “keeping it in the ground” is pretty much a whack-a-mole approach, i.e., quixotic. Crushing demand, as California has done — at least relative to the rest of the US — is the name of the game.