Among the gazillion articles, posts and books I read this year, three stand out.

Together, the three reads helped spark the Carbon Tax Center’s transformation from single-minded focus on carbon taxing and toward our new synthesis of taxing both carbon and inequality in support of a Green New Deal. As the year draws to a close, I want to share these pieces with CTC subscribers and visitors.

These shaped our thinking in 2019: Reporting on the ecological roots of the New Deal and the Gilets Jaunes protests, and a book on U.S. tax inequality.

Two of them, long-form journalism published in Harper’s magazine, plumbed the yellow vest protests in France and the ecological roots of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. The third, a searing, book-length exposé of tax inequality in the United States, is already reverberating in the current presidential campaign.

1. A Play With No End: What the Gilets Jaunes Really Want, by Christopher Ketcham, Harper’s, August 2019

(Full disclosure: Christopher and I are longtime friends, close enough that I wrote a eulogy to his stepmother, who died last month, and for us to have had several long conversations about his Gilets Jaunes story as he was setting it to paper last spring.)

The Gilets Jaunes movement, named for the yellow vests that French motorists are required to keep on hand for emergencies, rocketed to public attention last December when their largely rural protests against fiscal austerity reached the capital.

Ketcham drew on his direct observations of three tumultuous yellow vest marches in Paris last winter, in which he talked with hundreds of protesters — working and unemployed people and pensioners whose lives have teetered as their communities have been hollowed out by deindustrialization and megastores. He discovered that the Gilets Jaunes weren’t, as the mainstream media insisted, protesting climate action; they were rising up against the yawning gap separating them from the super-rich, a gap widened by President Macron’s rescission of French wealth taxes just weeks before he pushed through a modest carbon levy that raised prices of gasoline and diesel fuel but left aviation fuel untouched.

“The new carbon tax — nine cents more per liter of diesel, four cents more per liter of gasoline — may have been the proximate cause that galvanized the Gilets,” Ketcham wrote, “but the worsening conditions of what the protesters called “l’injustice fiscale” [fiscal injustice] provided the powder for an explosion.”

My conversations with Ketcham helped me appreciate the taint of unjustness that has come to surround stand-alone carbon taxing. That a carbon tax can, in theory, be made income-progressive — something this site has trumpeted for a decade — dissolves into irrelevance so long as the ultra-wealthy can consume fossil fuels with impunity while dominating discourse about our dependence on them.

One passage in particular in Ketcham’s article points to a possible escape from this dilemma — a passage I helped him craft on the roof of my apartment building in lower Manhattan, under the thwack-thwack of helicopters whisking the richest of the 1% to their weekend redoubts:

The war of the Gilets Jaunes against the rich, in the age of climate change, is one driven by an understanding unique to protest movements in France: that the privilege to lord and the privilege to pollute are one and the same.

If that is so — if the privilege to pollute is indeed the privilege to lord — shouldn’t we seek to tax both carbon and the super-rich?

2. Where Our New World Begins: Politics, Power and the Green New Deal, by Kevin Baker, Harper’s, May 2019

If Ketcham’s story put the lie to the media image of the yellow vests as know-nothing French trumpistas, Baker’s article resuscitated the Depression-era New Deal as an ecological project, not just an employment-creating and wealth-creating one. Indeed, in Baker’s telling, the New Deal’s three elements of jobs, production and care for the land were so intertwined as to have been one and the same.

Baker’s article begins in two disaster areas: the pre-TVA, flood-prone, impoverished Tennessee Valley, and the mid-thirties mid-American Dust Bowl:

In their desperation, the people of the Tennessee Valley had begun to cut or burn down more and more of the area’s once copious forests every year, seeking to clear more marginal land for farming, to sell the timber, or simply to heat their homes and cook their meals. Deforestation only further drained the soil, and what little land they had kept slipping away.

And this, about the high plains of eastern Montana, Wyoming and Colorado, across Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma and Arkansas:

The dust storms were not merely blown dirt, frightening as that might seem, but entire weird weather systems marching across the land. The static electricity they generated made fire dance along barbed wire and shorted car ignitions. It electrocuted farm animals and those few crops the blowing dirt had not already smothered — literally blackening vegetables in the patches where they lay. The people in the paths of these storms huddled in the darkness, unable to see their hands before their faces for hours, choking — sometimes choking to death — on the “dust pneumonia” that scarred their lungs as badly as if they had contracted tuberculosis.

Baker reminds us that the dust storms were human-made. Nineteenth-century warnings from the likes of John Wesley Powell — Colorado Plateau explorer and founder of the U.S. Geological Survey — that large-scale farming of the dry lands “beyond the hundredth meridian” was unsustainable, were plowed under by propaganda from mercenary railroads and their government enablers:

Much as the Trump Administration and corporate America react today to the idea of climate change or anything else they don’t want to hear by making stuff up, the government and the railroads … promoted quack theories to serve their purposes. No water? Don’t worry: there was always “dry farming,” “dust mulching,” and the imperishable notion that “rain follows the plow”— or civilization in general.

Linking Trump and today’s corporate America to their rapacious forebears is a constant refrain in Baker’s article. Another is pearl-clutching by mainstream gatekeepers such as The New York Times’ editorial board, both in 1933, opposing FDR’s fast-tracking of TVA authorization and funding (“enactment of any such bill at this time would mark the ‘low’ of Congressional folly”) and in 2019, decrying the sweeping ambition of the Green New Deal resolution from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Ed Markey (“the resolution wants not only to achieve a carbon-neutral energy system but also to transform the economy itself”).

To be fair, that 2019 Times editorial, The Green New Deal Is Better Than Our Climate Nightmare, offered some positives about the resolution. Yet The Times’ tunnel vision is on full display in the passage excerpted by Baker:

Read literally, the resolution wants not only to achieve a carbon-neutral energy system but also to transform the economy itself. As Mr. Markey can tell you from past experience, the first goal is going to be hard enough. Tackling climate change in a big way is in itself likely to be transformative. We should get on with it.

What Markey and AOC grasp, and, The Times may come to understand, though perhaps too late, is that, in Baker’s words, “We must address climate change, and we must transform the way our political and economic systems work in this country — just as we did during the Great Depression. There is no way to do one vital thing without doing the other.” While TVA, the Soil Conservation Service and many other New Deal initiatives were imperfect, as Baker notes, they pulled the land, and the country, together.

3. The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay, by Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman.

Saez and Zucman may not have intended it, but their new book — our third and final 2019 read — goes a long way to fulfilling Kevin Baker’s commandment to simultaneously address climate change and transform America’s political and economic systems.

That’s a high compliment for any book, and a particularly startling one for a book whose nominal subject is taxation. But reading “The Triumph of Injustice” is a revelatory experience, making clear just how much has been and is being stolen from working- and middle-class Americans to bloat the already criminally swollen coffers of the super-wealthy.

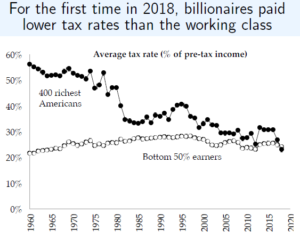

In 2018, for the first time in at least a century, and perhaps ever, Saez and Zucman report, billionaires — the 400 wealthiest U.S. families — paid lower tax rates than the working class, which the authors define as the bottom half of U.S. households. The respective 2018 tax rates were 23.0% for the billionaires and 24.2% for working class households. In 1960, Saez and Zucman’s graph informs us, the ratio of tax rates exceeded two-and-a-half to one (56.3% to 21.6%); even as recently as 1980, on the eve of Reagan’s ascent to the White House, the ratio was still close to two to one (47.2% to 25.7%).

These percentages are emblematic of American inequality. Plunging tax rates for those at the top of the income pyramid, engineered primarily through diminished taxation of capital (lower rates on capital gains and corporate income) have fueled what Saez and Zucman call “a snowball effect [whereby] wealth generates income, income that is easily saved at a high rate when capital taxes are low; this saving adds to the existing stock of wealth, which in turn generates more income, and so on.” The income pyramid grows ever steeper.

Snowballing is bidirectional. Burgeoning wealth at the top lets the super-rich buy heretofore unimagined political influence, not just through lobbying and campaign contributions but by creating and/or purchasing wealth-glorifying think tanks and media outlets. The result transcends ready-made votes in Congress and state legislatures to include an intellectual and cultural climate that valorizes the wealthy and stifles those who would counter the snowballing by taxing extreme wealth.

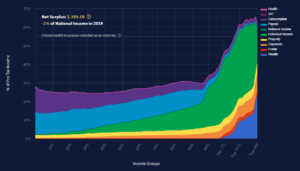

A signal achievement of “The Triumph of Injustice” is its painstaking construction of a century’s worth of tax incidence, not just at the federal level but state and municipal as well. The authors define eight or more tax categories — income, property, corporate, estate, wealth, payroll, consumption and health (the last encompasses payments for private and government health insurance) — and chart their “bite” for each income decile as well as for the top 1%, 0.1% and 0.01% and America’s 400 billionaires.

As if this tour de force weren’t enough, “The Triumph of Injustice” embeds its calculations and findings in a captivating narrative of American tax history from the colonial era through the Civil War, the Gilded Age, the New Deal, the postwar (and bipartisan) high marginal tax rate years, to Reagan’s tax renunciation (“Government is not the solution to our problem, government IS the problem”) and Trump’s tax “reform.” It’s illuminating and disturbing.

It wasn’t just tax erudition that vaulted Saez and Zucman to their status as architects of Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s and Sen. Bernie Sanders’ wealth tax plans. The likely clincher was their ability to calculate the revenue the Treasury stands to gain, year by year, through various permutations and combinations of raised taxes on capital (in the form of higher tax rate for capital gains, corporate income, and estates); and to explain how strong regulation backed by an aroused public could seal off the multiplicity of escape hatches from the higher taxes.

Somehow, “The Triumph of Injustice” delivers all this in just 200 pages. Even better, Saez and Zucman have posted their wealth and tax-incidence data on their website, taxjusticenow.org. The topper is their elegant, interactive page that lets you Make Your Own Tax Plan and see how the Warren and Sanders plans, or a plan of your own devise, can cut the holdings of the ultra-rich down to size and return American taxation to the relatively egalitarian shape it maintained from the New Deal through the Great Society.

Our Next Steps

At CTC, we are expanding our program around a new synthesis: a Green New Deal funded by taxes on extreme wealth — “taxing inequality,” you could say — and supported by a revenue-neutral carbon tax.

You can read more about this redirection here. We wish to emphasize that it is not an abandonment of carbon taxing. Far from it. Rather, we intend to situate carbon taxes in a broader framework that is suited to both the political dynamics and the climate emergency that will dominate the third decade of the 21st Century, and beyond.

Kyle Thomas says

This is EXTREMELY disappointing. Every open-minded but perhaps skeptical person who might find your site through a quest to learn more about carbon taxes will find that every aspersion cast on carbon taxes and climate action by the right as part of an agenda of wealth distribution appears to be confirmed by your “broadened” mission.

Tony Langtry says

I absolutely agree with Kyle Thomas. I believe a carbon tax (my preferred version of which is the carbon fee and dividend) is the tool most likely to reduce carbon emissions and avoid an existential threat. Mixing this up with an entirely separate desire to reduce inequality in the rich world, simply confuses the message and makes it vulnerable to political attack. The overwhelming priority must be to reduce carbon emissions – if you want to reshape capitalism, leave it to the many people who have spent decades trying (without notable success).

Charles Komanoff says

Dear Tony —

I too love carbon fee and dividend. I fought for it for most of the past dozen years, alongside Citizens Climate Lobby and its late beloved Marshall Saunders, to whom I proselytized it, early on. But CFD is going nowhere. The right foreswears *anything*that might help “solve climate” and the left disdains it as neoliberal weak tea. And, with a nod to Yeats, not much center remains.

I believe CTC’s new direction creates a potential path for CFD by placing it in a broader context. Letting wealth taxes pay for the Green New Deal allows the carbon fee revenues to be dividended since they don’t have to be invested in GND solutions — the wealth tax takes care of that. (I spell that out on this page, https://www.carbontax.org/blog/home_post/taxing-carbon-and-inequality-for-a-green-new-deal/, to which I linked in the last paragraph of the post.)

We are not abandoning the “overwhelming priority to reduce carbon emissions.” Rather, we believe our new direction offers a possible way to do just that.

Thanks for commenting.

Charles Komanoff says

Dear Kyle —

I believe I addressed (as best I can) some of your concerns in my reply to Tony Langtry.

I add, with respect, that I don’t think it helps our cause as climate-concerned carbon-tax advocates to be worried about aspersions cast by the right. IMO, if we’ve learned anything since the eruption of the Tea Party a decade ago and its successor outbreaks (Obama Derangement Syndrome, Trump, Trumpism), it’s a fool’s errand to try to placate the right.

Let me ask how you feel about the 2019 distribution of income, wealth and tax burden in the USA. More specifically, can you honesty look at the Saez & Zucman line graph of tax incidence by income cohort from 1960 to the present that appears in the third part of my post, and not feel revulsion … but at the same time not feel hope that the systematic transfer of wealth from the bottom and middle to the tippy tippy top over the past 60 years might propel a movement strong enough to do great things — including tax carbon and solve climate?

Thank you for writing.

David says

The Gilets Jaunes and similar protests against fuel taxes in many countries show that it is essential that carbon taxes not be seen to be a tax that widens inequality. Since average people spend a much higher portion of their income on fuel than wealthy people, that will indeed happen if there is no compensating mechanism included with the carbon tax This means it is essential to use the revenue from fuel taxes to reduce inequality. However, this article is poorly framed by mixing issues rather than addressing how best to implement carbon taxes and get them passed. The Green New Deal also mixes issues (as well as being unrealistic), so is not a good model if your primary aim is to prevent global warming. I hope the Carbon Tax Center gives this very careful thought as the future of the organization depends on getting this right.

Mike Aucott says

Charles, I have long admired your hard-headed focus on the need to price carbon, which you’ve backed up with solid numeric analyses. But your embrace of the GND and your intention to meld its advocacy with support for taxing carbon worries me. I don’t share your sense that the concept of taxing carbon is mired in “denialism from the right and derision from the left” or that it “dissolves into irrelevance so long as the ultra-wealthy can consume fossil fuels with impunity.” In my view, we may be approaching a tipping point in our national discourse, where it’s climate denialists’ posture that will dissolve into irrelevance and moderates will assert themselves and begin to take practical steps to mitigate climate disruption. There is a risk that the broadness of the GND will hamper more direct, step-wise actions that moderates might take. As has been said, “If you are for everything, you are for nothing.”

I completely agree that we have to address income inequality. But how do supporters of the GND intend to do this? With vast subsidies for renewables? Better to throw one’s support behind organizations, e.g. perhaps American Promise, that are directly focused on getting money out of politics.

I haven’t yet read Ketcham’s article or Saez and Zucman’s book. But to the degree that Ketcham focuses on France’s latest effort to price carbon, which was clearly regressive, I don’t see it as especially relevant to efforts such as those you’ve long advocated that would not be regressive, and which are embodied, for example, in proposed legislation such as the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act.

I read Kevin Baker’s article. While he describes the ecological disasters of the dust bowl and the ill-conceived farming efforts in the Tennessee Valley beautifully, his assessment of the effectiveness of New Deal policies in addressing these problems is naïve. He totally ignores the impact of the new technology of deep wells and center-pivot irrigation on the midwestern plains. While shelterbelts and other SCS efforts doubtless did some good, it was an end to years of drought by the 1940s, and later, center-pivot, deep well irrigation, that ended the dust bowl.1,2 Is the TVA, with its “16,000 miles of new transmission lines” dams that were “sparkling jewels and night” and that spawned “sports paradises of reservoirs” (and submerged hundreds of square miles of farms and settlements), and free nitrate fertilizer issued to farmers to “rebuild the soil”3 a good example of how we should deal with climate disruption? Do we really want another massive, in some ways heavy-handed, transformation of a large swath of the world? Could we really enact such a program today?

This brings me back to the likelihood that it is impractical to try for everything, and my conviction that in many cases, less is more. I urge you to maintain a distinctly primary focus on pricing carbon. Keep up your strong analyses based on hard numbers. Now is not the time to give up that ship, or to so enlarge that ship that it becomes unseaworthy in the face of the storms to come when Congress finally begins to tackle climate change.

1. See https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/how-center-pivot-irrigation-brought-dust-bowl-back-to-life-180970243/

2. Of course, that same technology is now slowly depleting the Ogallala Aquifer, and so eventually these western lands will have to revert to semi-desert. But, thanks to other new techniques in farming, including the development of perennial grains that can tolerate more dryness, we may not need conventional wheat and corn grown in this part of the world.

3. This is an example of Baker’s innocence of the realities of farming. While I don’t share the mantra of organic farmers that chemical fertilizers will poison the soil, the idea that free nitrate fertilizer will help build the soil doesn’t fly.

Djamel says

Concerning the “gilets jaunes” you “too conveniently” forgot to mention the 22cts diesel increase the 1/1/2018 where the real hangry started and matured at november 2018 with the few cents more .

Whihc made the “enough is enough”.

But I undertsand that you are a “carbontax” propagandists.

It’s a tax a TAX npthing else.

Can you explain how a TAX can solve an ecological.

Mainly when base on fake and false premisses, “CO2 guilty”.

3% of the total CO2 is human origin. Part is necessary, we breath too !

CO2 is necessary for plants, this is how nature works and it’s a kind of symbiosis between living organisma and plants !

The green new deal is in reality concentrated on “climate equality” whihc mean “climate control” via dangerous means like #chmetrails programs or climate control via sats and lasers/masers.

CO2 can’t be the reason for “climate warmin” nor “climate cooling” (whihc is probably happening…

The ONLY GOOD THING to do is to suppress this #carbontax BS.

It’s only a tax for people control and making them poorer thus more controlable.

The universal dividend as the name tells, is only possible when based on money creation process.

For sure the financial powers will not want it and that’s why we ended up with this BS #carbontax as the main distraction, played by the top psychopaths who think control this planet !!

Kyle Thomas says

Hi Charles,

Probably needless to say but I agree with Mike (and Tony). I think you are too readily dismissing the potential of the middle on this issue as Mike alludes to, particularly when you concede that the far left is hopelessly unreachable on the idea of carbon taxes. But regardless, in my simplified view of CTC a political calculation would not come in to play in the definition of the mission. As Mike stated, people rely on your site for a “hard-headed” treatment of carbon taxes. It should stay that way. I hope you will reconsider this decision.

Drew Keeling says

I support broadening CTC’s scope, as outlined on this page and the prior blog post here: https://www.carbontax.org/blog/2019/12/16/a-new-synthesis-carbon-taxing-wealth-taxing-a-green-new-deal/ . Mainly for a reason touched on elsewhere, e.g., see https://www.carbontax.org/blog/2019/03/14/carbon-tax-advocates-should-embrace-a-green-new-deal/ : The world has now lost too many decades failing to enact effective carbon pricing policies. When such policies were first widely mooted (c. 1990), CO2 was actually at the 350 ppm level from which the climate organization founded by Bill McKibben took its name. The level now exceeds 410 ppm. CO2 emissions are cumulative and the realistic changes of getting back down to 350ppm again in this century are near nil. Responsibly heeding the clear implications of longstanding solid science now requires more overt intervention. It is too late rely on reversing engines and swerving: Titanic is now heading straight into serious damage and there is no avoiding lifeboat launches, one way or another.

If major economic restructuring akin to a Green New Deal (GND) does not happen soon, many future generations will face much costlier adaptations to global systems increasingly outside the experience of our civilization and our species. The choice increasingly becomes not whether to support GND, but how.

CTC’s “redirection,” to my understanding, does not undo or weaken its extensive prior coverage of carbon pricing, although being concerned about and guarding against such undermining makes sense too. I am skeptical of new “inequality” tax revenues sufficing to fully cover budget requirements of a significantly effective GND, although that amounts to a technical detail in comparison. For GND, almost any normal funding mechanism is preferable to dozens of future generations paying dollars so we can have more pennies in our time. I also second the motion to back off from TVA references, and suggest referencing CCC instead.

However, while the synthesis of GND, “inequality” (e.g. wealth) taxes, and carbon taxes (e.g. “CFD”) looks appealing, it is not the only possible package. I do sense a considerable, albeit pluggable, risk with this synthesis: Unless revenue neutrality of the CFD component is cemented in (I see nothing per se “unjust” about such a carbon tax, even on a stand-alone basis: only a begged question of to whom its ‘dividends’ are distributed), politicians will be tempted to look at carbon fees mainly as a source of funds for GND projects. There would be nothing inherently unjust about that either, but it strikes me as unwise: a road to complexity, porkbarrelling, voter confusion, and ultimately repeated failure, as with recent experiences in Washington State. To avoid such minefields, hold out for a better deal: GND yes, preferably in a package including a substantial yet wholly distinct CFD, but in any case CFDs must non-negotiably remain 100% refunded.

For a robustly progressive yet politically marketable overall plan, perhaps arrange accounting such that CFD and inequality taxes can be readily measured together in terms of fiscal impact. If a sizable fraction of sizable wealth tax revenues are also progressively refunded, via a formula separate from, yet designed in tandem with, progressive CFD refunds, then it should be possible to keep nearly all moderate-carbon-using people in the lower economic c. 80% “above water,” even with a socially responsible hefty hike of carbon prices. To each according to need, from each according to monetary ability AND future-generational burdening. Instead of letting carbon taxes be milked for GND, insist that wealth taxes effectively help supplement carbon tax dividends, thus bolstering the middle class appeal of CFD.

Carbon taxation remains a very good idea for all the reasons long articulated by CTC. If, as plausibly argued here, the time has come to combine and leverage good ideas with other good ideas, in order to put them into prompt action, this “synthesis” looks to me like a solid and workable starting basis for that new emphasis.

Jonathan Marshall says

Charles, I personally share your desire for more progressive income and wealth taxes to pay for a variety of unmet social needs, including new infrastructure programs. However, you are wrong to say CFD is going nowhere. HR 763 has 75+ co-sponsors. With a new president and Senate, it could readily pass in 2021. Without them, we certainly won’t get much of anything, including new taxes on the wealthy. We need to keep pointing out that a carbon dividend scheme is one of the most fiscally progressive measures ever proposed, akin to a small but important universal basic income. I would also be cautious about touting the GND too much, when its details remain so murky. Say what you favor without appealing to an almost meaningless but polarizing brand name.

James Handley says

Dear Charlie,

First of all, ditch the “revenue-neutral” shibboleth. Marshall Saunders thought the “dividend” could attract Republicans. Nah.

Secondly, why not harness a carbon tax to fund the major infrastructure rebuild that will be forced upon us as climate breakdown ravages what we’ve got.

GND advocates who claim Modern Monetary Theory relieves us of budgetary constraints are delusional. Did you read Mankiw’s comment? Funding will be necessary, and as you’ve shown, an aggressively-rising carbon tax is absolutely essential to prod the needed transformation.

Two crucial polices that will work (and sell) better together. Green New Deal + Carbon Tax. It’s a no-brainer.

Galen Tromble says

I support the expanded mission. It recognizes that the drivers of wealth inequality and the continued opposition to rational climate policy are closely linked, and have led to such dysfunction and inequity in our economy that major changes are needed. I also agree with James Handley about letting go of the idea that revenue-neutral is politically necessary. We need a carbon tax and public investments that are up to the climate challenge – which is a lot bigger than it was a decade ago when CCL adopted the “this isn’t a tax, because we give it back” strategy, which hasn’t worked.

Drew Keeling says

Responding to the two preceeding comments, I would like to elaborate on why revenue neutral still looks best to me.

Of course, how greenhouse gas levels impact climate does not depend on the policy mix producing such levels. But we also face the political challenge of too little being done so far to ward off very costly climate change effects in decades ahead. Making GND dependent on carbon fee revenues, and carbon fees a carte blanche source for unavoidably politically contested infrastructure projects, seems to me likely to erode the political support for each, compared to keeping them independent (at least under foreseeable US political circumstances).

Recent vocal advocates for carbon pricing favor revenue-neutrality, largely because it incentivizes decarbonization without government “interference” beyond (partially) correcting for the market failure of underpricing the social costs of fossil fuels. Some perhaps amenable “purple” state senators, however, would more likely vote against an integrated “tax and spend” GND+carbon-tax. Others, though against carbon pricing, might nonetheless support a GND not tied to a guaranteed funding stream coming from a regressive tax.

Younger and future generations cannot afford more experimentation and legislative failure. Whatever strategy has the best odds of actual enactment is the best strategy, and a GND without a CFD, or vice versa, is better than both joined at the hip going down in flames together. They can still be part of the same overall “synthesis” or campaign platform, and together with a “climate equity” spigot tapping redistributive taxes on high wealth and income. Most voters could get an annual carbon dividend check, and a wealth redistribution check, and some (hopefully) nice and well-functioning local new green infrastructure, by each piece getting approved by each constituency for it. Why risk insisting on attracting the same majority for each pillar of the program?

Michael Howard says

An additional reason for pursuing a suite of policies, CF&D, taxes to reduce inequality, and the GND, is that it may be too late to reduce emissions through carbon pricing alone. Use the online calculator to see what kind of pricing would be needed to reduce emissions rapidly enough to stay below 2C (not to mention 1.5C), and it’s not clear that the economy could respond smoothly to such rapidly rising prices, as opposed to falling into recession. Carbon pricing, complemented by war-mobilization-scale investments in energy alternatives may have a chance of getting us where we need to go.

Robert A Archer says

Charles–Many thanks for the work and advocacy you have done for the carbon fee and dividend policy. It is unfortunate that you mis-characterize where we are. The steady advance of the policy over the last 12-15 months has resulted in the introduction of HR 763 (Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act) with nearly 80 sponsors in the House. Similar bills in the Senate with even steeper annual increases in the carbon fee bring the number of bills to six. The policy debate this year has a very good chance of leading to a major bill passage in 2021 (if November turns out right). Some commenters say ditch the dividend and wrongly cite that it was a bone tossed to conservatives. Only partly accurate. What is rarely mentioned by advocates of spending the revenues (on a wide array of “good things”) is that they are putting the disproportionate burden on the poor and middle class by taking away the dividend. It is the inconvenient truth that has been part of the history of environmental groups for decades and still persists (e.g., Sierra Club, etc.) You may have noted that the Economists Statement signed by all former Fed Chairs, heads of the CEA and 27 Nobel Economists and 3500+ economists called for a full dividend because of its equity and political sustainability. They have clearly said that the traditional priority of economic efficiency (i.e., tax swaps, productive infrastructure, etc.) are now secondary to equity and sustainability. It is ironic that the climate advocates ignore or gloss over this. And no, spending it in disadvantaged communities like in California doesn’t address the real equity problem–it addresses the politicians problem of getting cap and trade approval. That policy may help a million or so but will leave the other 11 million low income as outsiders. Leaving behind the carbon fee and dividend policy as Senator Sanders has done is folly. It is the foundation policy that will have the widest impact and also requires passage of complementary regulatory/subsidy programs where the carbon fee does not reach or has inadequate impact such as rental housing, agricultural sequestration, forestry, enteric fermentation etc. Debating over the fee revenues is a trap discussion. Everyone knows significant huge expenditures are needed. Taking away the dividend from the low- and middle-income households is not a defensible policy.

The Green New Deal is mostly “what” has to be done with little on “how” it will be done with regard to either the climate component or the socio-economic component. Whatever emerges will be in a range of separate bills based on the priority that emerges for each. Without a sound climate approach, none of the socio-economic measures will likely even approach addressing the damage to come.

Charles Komanoff says

Robert — I completely agree that fee-and-dividend deserves to be the foundation for climate policy. (And by the way, thank you for your kind words up front.) My departure from you and Citizens Climate Lobby et al. is in my conviction that fee-and-dividend is not going to be enacted, at least not at any meaningful price level. The right will never sign on, and the left (or, at least, Democratic) majority we hope for after November will, regrettably but understandably, be unable to resist the appeals for compensation and investment that, as you note, are mutually exclusive with revenue dividends. I honestly believe that CTC’s emergent calls for extreme-wealth taxation will open up political and policy space for fee-and-dividend by creating the pay-for for compensation and investment. In short, CTC isn’t abandoning fee-and-dividend, it’s opting for a broader canvas that can actually enact it. — Charles

benjamin d weenen says

Taxing externalities makes moral and economic sense. Politics can be tricky because humans love dumping their costs on others. But economists and fair minded people agree this is best policy.

Being wealthy does not in and of itself harm others. Taxing it is unfair, evidenced by the undesirable deadweight losses it causes. Yes, inequalities are too high, so we should strive to find out their root cause and deal with that directly.

As it happens, the main cause is known and in principle easy to deal with. Land is supplied free of human inputs and its wealth/welfare creating potential varies greatly between locations. Thus if those excluded from its use are not compensated for their loss of opportunity, excessive inequalities and resource misallocation are baked in.

A 100% tax on the rental value of land re-distributes incomes, in doing so drops its selling price to zero along with any inequalities that result from its mere ownership. This alone many solves issues such housing affordabilty for the young and typical working households.. Such a tax has no deadweight loss, indeed it corrects existing market imperfections.

A tax on carbon and a land tax have the same rational. I would therefore recommend you stay consistent in the policies you promote.