I was there to catch a man

I thought I had him by the hand

I only had him by the glove

The War on Drugs, I Was There, 2011

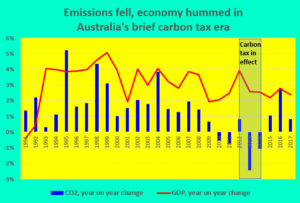

Australia, engulfed in flames, choking in smoke, a billion animals perished, once had a powerful climate solution by the hand: a carbon tax. The nationwide tax on fossil fuels was in effect for just two years, but what an impact it had, helping the country cut its carbon emissions while economic activity climbed unimpeded. During the carbon tax’s middle year, 2013, Australia’s CO2 to GDP ratio had its sharpest drop ever (see graph below).

Lake Conjola in New South Wales on the last day of 2019. Photo by Matthew Abbott, courtesy NY Times.

Australia stands apart, then, not just in the magnitude of its climate-charged horror but in deploying a climate-change antidote, only to lose it to a right-wing, coal-financed backlash. Not even Trump’s dismantling of the Obama pro-climate Clean Power Plan and auto-mileage standards, unsettling as it has been, stands out as cruelly as Australia’s renunciation of its carbon tax.

Unwanted child, stepchild, bastard child … Australia’s carbon tax was all of that. It took effect on July 1, 2012, the keystone of a deal between the Labor Party headed by incoming prime minister Julia Gillard and the pro-carbon tax Green Party, whose votes Labor needed to attain a majority.

As Australian journalist Julia Baird noted in a 2014 NY Times op-ed, Gillard’s earlier pledge to not tax carbon emissions and her “perceived lack of conviction in the policy itself” damaged the tax’s credibility and her own viability. The subsequent electoral victory of a “Liberal” (read: right-wing) government committed to repealing the tax led to its rescission on July 17, 2014.

Yet the tax appears to have performed brilliantly. With just two years of data, we can’t draw sweeping conclusions. Nevertheless, we have these ineluctable facts about the 24 months in which Australia taxed carbon emissions from all major sources except petrol-fueled transport:

- CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels in Australia fell 2.4 percent in 2013 and 1.1 percent in 2014 — the two steepest year-on-year declines since 1990, when modern record-keeping began.

- Emissions in 2014 were 14 million metric tons less than in 2012. The decline was powered by a 19 million metric ton drop in the electricity sector, which is highly carbon-intensive and thus the most responsive to carbon pricing. (Increases in mining and manufacturing emissions somewhat offset that downturn.)

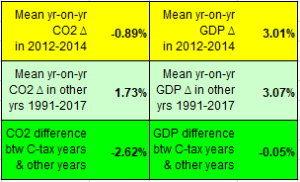

- Economic activity was unaffected by the carbon tax, as indicated by the minimal difference between the 3.01% average annual rise in GDP for the years 2012, 2013 and 2014 vs. the 3.07% average rise for the remainder of the 1990-2017 period for which we had data.

As each day brings new stories of suffering from the terrifying temperatures (including a continent-wide average 107.4ᵒF on Dec. 18) supercharged by climate change, we can only speculate what might have turned out differently if the country hadn’t abolished its carbon tax in 2014.

Calculations by author, from data posted by Australian Greenhouse Emissions Information System, Department of the Environment and Energy. CO2 figures include all sectors except Agriculture, Forestry & Fishing. GDP data are from World Bank and in constant US dollars.

For one thing, the 18 million metric ton rise in nationwide emissions since 2014 (to 2017, the last year for which the government has issued data) might have been averted if the carbon price signal had stayed in place. Emissions might even have shrunk if the tax had risen from its roughly $20 per ton level — and if the national government had embarked on a New Deal-style project to harvest the country’s vast solar and wind resources.

Even more, Australia’s action might have rippled through the world. The example of a proudly macho and avowedly hedonistic society explicitly pricing its carbon emissions could have turned heads, particularly in the United States, with its many cultural resemblances to Down Under. The fantasy of a land that produced Mad Max and Crocodile Dundee serving as a global role model for carbon taxing and reduction is delicious, though alas, no more than that.

Had Australia continued taxing carbon, British Columbia, the other English-speaking jurisdiction with an explicit carbon tax, wouldn’t have been dismissible as a unicorn. Carbon tax campaigners in, say, Washington state, whose voters considered but rejected a carbon tax in 2016, would have had more than one drum to pound.

Stark difference in CO2 emissions between three years in which Australia’s carbon tax was in effect and rest of 1991-2017.

It could be said, of course, that Australia’s rescission of its carbon tax is merely one of a number of missed opportunities around the world to tackle climate change by transparently pricing carbon emissions. In an alternative U.S., influential left-greens like Van Jones, Naomi Klein and Food & Water Watch might have backed that Washington carbon tax referendum — or, at least, not lent their voices to the opposition. Earlier, at the start of the Obama presidency in 2009, U.S. “big green” groups could have thrown their weight behind straight-up carbon taxing rather than try to muscle the convoluted, Wall Street-friendly Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill through Congress.

But Australia’s fateful choice is harder to bear. A country of 26 million people didn’t merely pass up a potential opening six years ago; it turned its back on an actual, promising beginning by bringing to power a confirmed climate denier, Tony Abbott, who axed the tax in 2014 and just a month ago, as his country was becoming a cauldron, complained to an Israeli radio audience that the world was “in the grip of a climate cult.”

When summer ebbs and the fires and smoke recede, Australians should consider how and why they disarmed themselves in the fight to stop climate change; and then make a new start by reinstating a policy that, in the brief time granted, appears to have worked wonders.

For more on Australia’s carbon tax history, click here (the Australia section of CTC’s “Where Carbon is Taxed” page).

Drew Keeling says

Highlighting opportunities for Australia’s 2012-14 carbon tax to have “rippled around the world” hits the nail on the head. Climate change risks are not just intergenerational, they are also cross-border. Without international collaboration of some kind, policy responses are typically beset with “free rider” drawbacks.

Australia’s carbon tax benefited the whole world, though it “paid” the “price”; canceling that carbon tax harmed the whole world, while Australia “saved” by no longer paying. Analogously, though in reverse, cumulative global emissions are disrupting the global climate, making (for instance) catastrophic fires in Australia more likely than before, even though negative effects of such fires mainly fall just on Australia. Like it or not, admit it or not, climate challenges interlink the whole world and likely will for centuries to come.

Along with other congruent policies (such as “green new deal” infrastructure, and wealth taxes), suitable for alignment with efforts at carbon tax enactment, more explicitly adding in compensatory “tariff” or other “border adjustment” mechanisms could be advantageous. That topic is covered here:

https://www.carbontax.org/issues/border-adjustments/

Especially in light of recent (though mixed) experiences with unilateral tariff actions, border adjustments as part of carbon pricing arrangements would appear ripe for near term revisiting, both generally and in a multilateral context.

Michael Howard says

Since there is no mention of a carbon dividend, I assume that the revenue from the carbon tax was used for other purposes. Would a carbon fee and dividend policy have been more robust in the face of repeal efforts?

Jim Allen says

Some of the carbon tax was returned to households but this was badly sold by the ALP Government. Australia’s leading climate economist briefly reviews what happened in his excellent book ‘Super Power’ released in November 2019.

These are some of the things he says:

ALP mistake with carbon price: “The government made little attempt to explain the link between the increased cost of living from carbon pricing and the reductions in income tax and increases in social security payments. One view among political strategists for the government saw more political advantage in taking credit for the income tax and social security changes and saying as little as possible about carbon pricing. That did not help the political standing of the government’s policy on climate change.”

On electoral rejection – the evidence is equivocal. More support in opinion polls for carbon price than the Coalition’s ‘direct action’.

“The Abbott government came to office committed to repealing legislation supporting the carbon price, the ARENA, the CEFC and the CCA. Once in office, the Abbott Government added abolition of the RET to its repeal list. In a remarkable episode, the Palmer United Party…used its numbers to block repeal of the Abbott legislation, excepting only carbon pricing.”

Carbon pricing coincided with electricity prices rising for other reasons – “major regulatory mistakes following the privatisation and corporatisation of electricity utilities greatly increased the cost of electricity transmission and distribution to users”; making gas portable raised their prices to Australian power generators by hundreds of per cent. “Third, the domination of each state market by a small number of generator-retailers led to oligopolistic pricing, rather than the competitive market that had been presumed in setting up then system”. “Finally, uncertainty about policy through the long political contest reduced investment in electricity generation, reduced supply and increased wholesale prices.” (pp70-2)

Is Australia worse off?

“Uncertainty in energy policy has contributed to electricity prices being much higher than when the carbon price was operating – with no government revenue to compensate low- and middle-income households.”

Repeal didn’t stop mitigation action but it increases the costs and reduced its effectiveness.

Buy the book! It is one of the most important books to read right now about Australia’s future and a low-carbon future more generally.

Dick Smith says

In your email to this blog post you led with Paul Krugman’s op ed (linked to the phrase, “climate hell.”)

CTC featured Australia to rebut one of the most widespread, but false, assumptions about carbon taxes—that they are a drag on the economy.

Unfortunately, CTC linked to a Paul Krugman op ed that repeats the second most common, but equally false, assumption—that carbon taxes are not viable because they require “widespread sacrifice.”

Krugman concludes: “This means, in turn, that climate action will have to offer immediate benefits to large numbers of voters, because policies that seem to require widespread sacrifice — such as policies that rely mainly on carbon taxes — would be viable only with the kind of political consensus we clearly aren’t going to get.”

The truth or falsity of Krugman’s assumption that carbon taxes necessarily require widespread sacrifice depends what you do with the carbon-tax revenue. There are smart ways and stupid ways to allocate the carbon-tax revenue.

As CTC knows, the carbon fee and dividend proposal endorsed by Citizens’ Climate Lobby (HR 763) returns all net carbon fees in equal shares to all adult Americans (with a half share to the first two children in a family) With that distribution, most American families would be net financial winners. This is overwhelmingly true among the lowest 60% on the income scale. Yes, the cost of carbon-based energy will increase. That’s the whole idea of the fee. However, most American families will get more back in the monthly dividend checks than they will pay in rising energy prices. And, to be clear, that includes both direct energy cost increases for power at the gas pump and the electric meter, and indirect energy cost increases related to the production of all other goods and services. This remains true no matter how high the carbon fees rise.

And, REMI (Regional Economic Models Inc.) studies confirm that the additional consumer spending of these dividend checks will increase GDP every year during the 20-year study period, and create 2.1 million net new jobs within 10 years, and almost 3 million net new jobs by the end of the 20-year period. So, the argument that carbon taxes are necessarily a drag on the economy is false (as your shorter, 3-year Australian sample also demonstrated).