Calculations by the Carbon Tax Center suggest that the worldwide economic contraction from steps being taken to slow the spread of deadly COVID-19 could halve this year’s rise in the atmosphere’s carbon dioxide concentration.

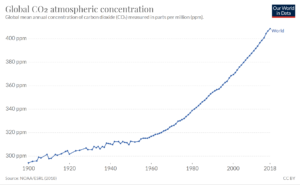

The last time average atmospheric CO2 rose less than 1 ppm was 1993. Could 2020 do likewise? (Graph is from “Our World in Data” website mentioned and linked to below.)

This finding is largely illustrative and encased in caveats. First, the average CO2 level wouldn’t actually fall; rather the business-as-usual annual rise of around two ppm would be trimmed to just one. And for that to happen, the slowdowns in travel, industrial production, goods movement and commercial activity, and the accompanying reductions in use of fossil fuels and carbon emissions, would have to be steep and prolonged, as our calculations show below.

The most critical caveat, of course, is the widespread deaths and massive dislocations bound up with these events. Megadeaths and cataclysmic job losses are not anyone’s preferred path for slowing climate change. Nevertheless, the calculations provided here may be instructive.

U.S. Reductions

Federal bean-counters divide U.S. energy use into four categories: Industrial, Transportation, Commercial, Residential. We assume that the first three contract by 50 percent as factory production tumbles, aviation evaporates, commuting recedes, recreational travel dissipates, and offices, stores and performance spaces remain empty. (April 2 addendum: U.S. gasoline demand for the week ending March 27, before the economy fully shut down in all 50 states, was 27 percent less than in the same year-earlier week, according to Energy Information Administration data.) We assume that residential energy use, which currently is around a fifth of the total, rises by 10 percent due to enforced home-stays.

These assumptions add up to a 37 percent shrinkage in U.S. energy use measured in Btu’s. The fall in carbon emissions might be a bit greater since carbon-free energy sources — nuclear power, wind turbines and solar panels — would keep humming while dirtier coal and petroleum bore the brunt of the cutbacks. We’ll watch to see how other modelers handle the complex calculations.

Rest of World

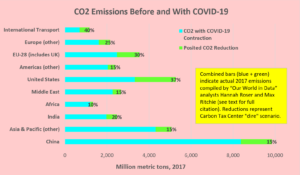

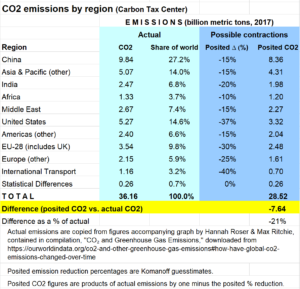

U.S. carbon emissions now (2017) account for only 15 percent of the world’s total. To baseline the rest of the world’s CO2 we turn to the superb data compilations and visualizations assembled under the aegis of “Our World in Data.” Analysts Hannah Roser and Max Ritchie divide the globe into nine regions, plus International Transport (largely long-distance shipping and aviation).

We assigned various percentage reductions to each region as shown in the graph at right, starting with our U.S. figure of 37% derived above. Other reductions range from highs of 40% (International Transport) and 30% (European Union) to lows of 10% (Africa) and 15% (most of Asia; also Latin America). The worldwide average — again, this is speculative calculating — is 21%.

We again stress that these are guesses and are skewed to the high side; as dire as things are, it still seems unlikely that fossil-fuel burning and consequent carbon emissions will fall this steeply. Moreover, deep contractions probably won’t be sustained for a full year.

Translating CO2 emissions to CO2 levels

The numbers are largely illustrative and we’ve pushed them hard. Summing the reductions shown in the graph, they imply that 2020 emissions conceivably could fall short of the 2017 baseline or “default” value by 7 to 8 billion metric tons (gigatonnes).

The redoubtable “Skeptical Science” brief, Comparing CO2 emissions to CO2 levels, tells us that each 7.8 gigatonnes of emitted carbon dioxide adds 1 part per million to atmospheric concentrations of CO2. Equivalently, reducing emissions by 7-8 gigatonnes — whether absolutely or relative to a baseline trajectory — averts a 1 ppm rise in atmospheric CO2.

Keep in mind that this would constitute a permanent drop. Atmospheric concentrations of CO2 would be 1 part per million less than otherwise not only at the end of 2020 but at the end of 2021, 2022 and every year going forward. The boon to climate and humanity, though slight (considering that the world has overshot the postulated 350 ppm maximum safe level by more than 50 ppm), would be indelible.

We hope in future posts to explore how much of the current reduction in CO2 might be negated by economic “bounceback” (short answer: not much); and, more importantly, how the economic and social upheavals from the coronavirus crisis might open up political pathways leading to decisive, longer-term action to bring down carbon emissions without widespread suffering.

Addendum, April 11: See our new post today, CO2 emissions will shrink this year. How much?, for a discussion of parallel but different projections of worldwide 2020 CO2 contractions from Carbon Brief.

Drew Keeling says

This is a timely and important analysis. The many trillions of dollars question posed at the conclusion remains open, however: How and how much “the coronavirus crisis might open up political pathways leading to decisive, longer-term action to bring down carbon emissions without widespread suffering.”

In its recent piece (‘The epidemic provides a chance to do good by the climate; chances are, though, that it will not be taken”), Economist magazine is rather pessimistic, calling the “long-term outlook” still “grim” (first quoting a Belgian researcher, then extrapolating further):

“ ‘The climate needs a sustained drop in greenhouse-gas emissions, not a year off’.‘ Unfortunately, not only is that unlikely to happen, but the response to the crisis could easily make things worse.”

Partly this is a question of the post-epidemic “bounceback, ” which Economist deems “entirely a matter of politics.” More important may be whether leading democracies prove capable of seriously heeding some key lessons from this preventable pandemic. In the context of climate change, arguably the most crucial “take home” realization could and should be that, if they focus forthrightly on what is most profoundly at stake long term, governments are still quite capable of swift, radical, and significant tangible changes to public policy.

Jan Freed says

I believe there is an error in the above. Not all the CO2 emitted remains in the atmosphere. So 8 gT of CO2 not emitted does not mean 1 ppm not emitted. Although 1ppm weighs 8 gT, if we do not emit 8gT perhaps only 4gT remains in the air (or 1/2 ppm) after the other half was absorbed by land and sea. C0rrect me if I am wrong.

Jan Freed says

I should have said…. “perhaps only 4gT would have remained in the air” oops.

Jim Lazar says

This is an important analysis, and we hope that some of the contraction we are now seeing becomes permanent.

The one area that gives me the greatest hope is coal plant closure. Natural gas prices, at least in the USA, are so low that almost no coal plant in the country has positive economics. If they are closed, and the staff furloughed, many will never reopen.

Another area with some promise is that people staying home more will give them an incentive to invest in efficiency measures at home, and these will persist long after a vaccine is developed in a year or two.

Finally, hospitals are buying lots of new equipment for ICU deployment. If that equipment is newer, it may well be more efficient than existing equipment, and it will become the primary equipment, relegating older, less-efficient equipment to backup service.

However, I fear that all of this will be overwhelmed by fear of transit in the future. If we can convince people to walk and bicycle, that’s promising. But I think the more likely scenario will involve de-urbanization and longer solo commutes.

Jan Freed says

Grisly silver lining: Pollution kills 4 million / year. There is less pollution so some lives are to be saved.