I posted this on Streetsblog yesterday, April 22, the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. It’s NYC-centric and doesn’t mention climate change (!). But its lessons apply nationwide, and good news is always welcome, especially now. PS, there is Covid-19 content, toward the end. — CK.

On Thanksgiving Day in 1966, I was driving from my parents’ home in suburban Long Beach, NY to dinner with family friends in Forest Hills, Queens. The air seemed extra bad. My eyes were teary, my nostrils were twitching and the radio was reporting some sort of pollution episode.

At that very moment, New York Times photographer Neal Boenzi was memorializing what the air looked like from a perch high up in the Empire State Building: smog shrouding skyscrapers like Met Life, NY Life and the Flatiron Building; smoke obscuring the financial district; the Hudson and East Rivers, invisible.

Fast forward 50 years to a mid-September weekday in 2016. Former New York City government official and activist Jon Orcutt steps onto the India Street Pier in Greenpoint, Brooklyn and aims his iPhone at east Midtown. The contrast of his photo with Boenzi’s couldn’t be more stark, and not because one was black and white while the other was color and digital. Ocutt’s picture glistens with mountaintop clarity. Zoom in, and every building — every window — is distinguishable. Billowing clouds adorn the sky, multitudes of pristine blue and pellucid white.

The distance between the photos attests to the past half-century’s clean-air revolution — a vast do-over to our nation’s skies, much of it led by New York City. Through citizen activism, enlightened governance and innovative technology, pollution levels were slashed across the board. No one knows the precise extent, but my best guess is that from the late sixties to today, citywide levels of noxious pollutants like PM2.5 (tiny particulates that invade and obstruct the lungs) and photochemical smog (a gaseous soup cooked by sunlight from nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds) fell by over 80 percent. Another lethal pollutant, sulfur dioxide, almost certainly declined even more. (The writer-activist Bill McKibben reported this week in his weekly New Yorker magazine climate newsletter that “air pollution has dropped by more than sixty per cent across America since 1970.”)

These improvements didn’t just enhance public health and cut medical costs. They also contributed to New York City’s economic resurgence. Here, too, no one knows precisely how much; polls don’t ask if cleaner air factored into people’s decisions to settle here. But my guess is that, after reduced street crime, cleaner air has been on a par with better schools and improved public transportation in attracting and retaining residents and businesses to New York.

No single regulation or program or anti-pollution device wrought these striking gains. Rather, a multiplicity of initiatives reduced air pollution levels here. These have probably been key:

- Lowering five- to 10-fold the sulfur content of fuel oil burned for heating and power generation*

- Tailpipe and engine technologies that cut per-mile auto emissions at least 10-fold

- Cleaner fuels and engines for diesel-powered heavy vehicles (still a work in progress)

- Investments in mass transit that stanched growth in auto travel (partly undermined by Uber)

- Widespread switching of dirtier oil-fired power, furnaces and boilers to natural gas

- Decommissioning in-building incinerators

- Controls on emissions from upwind sources such as refineries and power plants

* = CTC readers will enjoy my 2009 post in Grist relating how NYC’s 1972 emergency surcharge on dirty oil — an early instance of Pigovian taxation — protected the city’s low-sulfur oil regulation from oil industry interference.

These developments didn’t happen by themselves. They were, and are, the most visible and impactful fruits of the environmental movement whose arrival 50 years ago as a political and cultural force we mark on Earth Day today. At its forefront were the Natural Resources Defense Council and NYC-based organizations such as Citizens for Clean Air (which preceded Earth Day), Straphangers Campaign and Transportation Alternatives (which came in its wake); indefatigable campaigners like Gene Russianoff, Marcy Benstock, Rich Kassel and the late Carolyn Konheim; and proactive city officials like Mayor John Lindsay, his Environment Commissioner Jerry Kretchmer, and engineering dynamo Brian Ketcham. In turn, these individuals and institutions were backed by (and often preceded and helped spark) federal environmental legislation enacted in the national upwelling of environmental activism that took full flower in the early 1970s.

It is true, and shameful, that, nationwide, communities of color today breathe dirtier air than wealthy, white areas (though in New York City there is surprising overlap between affluence and pollution). Even so, air quality has risen significantly in most environmental justice communities in recent decades, with more gains likely as ecological activism grows increasingly black- and brown-led, although that, of course, depends heavily on the outcome of the next election.

I have labored in recent years to foster appreciation of air quality progress, especially in New York City. Valorizing environmental regulations and, at least implicitly, the scientists, attorneys and activists whose labors and expertise brought them into being, isn’t just right, it’s an investment in protecting and enhancing our environment going forward.

Well, my project has a ways to go. Case in point: this statement in a recent New York Times story on a preliminary Harvard School of Public Health study linking higher levels of PM2.5 pollution with increased COVID-19 deaths:

If Manhattan had lowered its average particulate matter level by just a single unit, or one microgram per cubic meter [µg/m3], over the past 20 years, there would have been 248 fewer COVID-19 deaths in Manhattan by that point in the outbreak [April 5].

That framing is completely backwards, in my view. Rather than bemoaning the failure to reduce New York pollution levels by one hypothetical unit, we should be celebrating the reductions already accomplished. They are enormous: almost certainly more than 20 µg/m3 since 1970 (early baseline data for New York and other cities is sketchy). If the preliminary link between particulate pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the Harvard study is confirmed, then NYC’s pollution reduction since the time of Earth Day will be shown to have spared vast numbers of lives through population-level improved lung functioning.

(The linkage between polluted air and COVID-19 mortality is this, in a nutshell: the coronavirus kills primarily by ravaging people’s lungs, while chronic exposure to fine particulate matter and other air pollutants degrades lung functioning, rendering inhabitants of polluted areas more vulnerable once they’ve been infected. Conversely, the advent of cleaner air has given New Yorkers a hidden but sizable degree of immunity, relative to our susceptibility if the air had remained chronically polluted.)

It’s tempting to recast the pull-quote from the Times in terms of thousands of New York City COVID-19 deaths already averted, but I’m going to demur. For one thing, the hypothetical 248-lives figure there (which the Times article took directly from the preliminary Harvard paper) was calculated from a baseline of citywide deaths and ascribed (incorrectly) to Manhattan alone. More importantly, I’m not convinced that the correlation between PM2.5 pollution and COVID-19 mortality is as strong as the paper contends. Despite laudable effort by the authors, their county-level analysis may not have been fine-tuned enough to fully control for the 17 different possible confounding factors they included in their model such as population density and education levels.

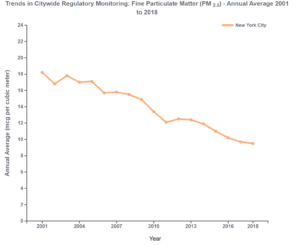

Consider that from 2001 to 2017, a period rigorously analyzed by environmental-health experts at NYC’s Department of Health, citywide average PM2.5 levels declined from around 18 µg/m3 to around 10 (see graph). That’s a drop of 8 µg/m3 in just 16 years. If we extend that rate of improvement backwards to the three decades leading to 2001 — when many of the innovations I bulleted earlier were taking effect — the drop in PM2.5 in that period would be around 16 µg/m3. That would yield an overall reduction of 24 µg/m3 in fine particulate pollution levels from Earth Day to today.

But today, let’s lift our gaze from COVID-19 and epidemiology to New York’s clearer skies. Dear reader, please join me in toasting a half-century of scientist and activist vision and grit that has made — and continues to make — our city cleaner, healthier and more beautiful.

Peter Joseph says

You’re so right, Charles. As a biology major at Columbia in 1966 I remember wiping the soot off my face at the end of each day and thinking “this is not healthy.” I left for the clear skies of Ann Arbor for med school. It’s so much better now.