As in 2016, Democrats appear poised to capture the White House and perhaps the Senate while retaining the House. Let’s explore what a Democratic presidency and Congress might mean for climate policy and carbon taxing.

Caveats first. We offered a similarly rosy prediction in 2016, a month before Election Day. In a post on Oct. 9, The Political Meltdown That Could Save the Climate, we said that the “Access Hollywood” tapes were leading “shell-shocked Republicans to abandon the Trump ship.” Little did we know that the Trump campaign was already detonating a wave of counterattacks that would culminate in FBI director James Comey’s catastrophic Oct. 28 letter to Congress dredging up Hillary Clinton’s emails. Nor did we imagine that most swing-state voters who disliked both candidates would pivot sharply from Clinton, or that her seemingly impregnable lead was partly an artifact of pollsters’ under-representation of Trump’s top demographic, non-college white voters.

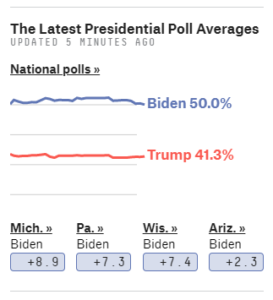

In mid-July, Biden was sitting on comfortable leads in the three Rust Belt states that swung the 2016 election to Trump, according to FiveThirtyEight.

Even more wild cards abound this time: possible election intimidation and interference, Covid-related voting reluctance, and of course Trump’s proven willingness to say and do almost anything to hold onto power. Plus, the election is still 16 weeks away — “an eternity in politics.” Nevertheless, Biden’s position today looks stronger than Clinton’s four years ago.

With Democrats rallying solidly around Biden, the trifecta of Covid, economic privation, and revulsion at white supremacy may be too much for the incumbent to overcome. At this writing (July 14), FivethirtyEight.com has Biden leading by at least 7 points in the three states that tipped the 2016 election to Trump. As for the Senate races, though polling is thinner, Democrats are being given the edge in a majority of the eleven most competitive races; they need only take five to gain the majority (four if Biden wins).

So let’s make the optimistic assumption that the party of climate denial, tax inequality and All Lives Matter is trounced this November. What’s in store for climate and carbon pricing?

Tackling Inequality and Climate Change

New York Times columnist David Leonhardt last week singled out the Democrats’ agenda’s “two defining features”:

The first is reducing inequality — through higher taxes on the rich, greater scrutiny of big companies, new efforts to reduce racial injustice and more investments and programs for the middle class and poor, including health care, education and paid leave. The second is acting on climate change. (From It’s 2022. What Does Life Look Like?, July 10; emphases added)

Those two elements overlap with the three building blocks we articulated for climate progress in our Dec. 2019 post, A New Synthesis: Carbon Taxing, Wealth Taxing & A Green New Deal.

Leonhardt contends that while “[Joe] Biden may not seem like a history-altering figure, certainly like less of one than Barack Obama did. . . he could wind up presiding over a larger scale of political change than Mr. Obama did, for reasons largely independent of the two men themselves.” One reason is that unlike the start of Obama’s presidency, which coincided with the onrush of the 2008 financial meltdown, “today, by contrast, progressives have spent years working through the details of plans on climate change, high-end tax increases, antitrust policy and more.”

“There is a whole vision that I think is ready,” says economist Heather Boushey, who runs the progressive-leaning Washington Center for Equitable Growth, and whom Leonhardt quotes. “And there is a lot more runway,” she told him, contrasting the ten or so months Biden’s team will have had to lay out their plans with the mere two months available to Obama.

The other factor militating for potentially sweeping legislative change under Biden, in Leonhardt’s view, is the vast scope of disruption in the past two decades. This period includes “the biggest two economic crises since the Great Depression, the worst pandemic in more than a century and the election of two presidents unlike any before them — and diametrically unlike each other.” He could also have mentioned the breadth and militancy of the resurgent U.S. left, which has served notice that it has no intention of letting up or bargaining down during a Biden presidency — a perspective that suffuses another, more visionary essay that the Times published alongside Leonhardt’s, The Left Is Remaking Politics, by Ohio State University law professor Amna A. Akbar.

Standards-Investment-Justice: an emerging Democratic Party alignment on climate

In late May, Vox climate writer David Roberts published At last, a climate policy platform that can unite the left, a monster (6,000-word) post drawing on his decade covering U.S. energy and climate policy and politics.

Roberts posits, and offers as his post’s subhead, that “the factions of the Democratic coalition have come into alignment on climate change.” “For the first time in memory,” he writes, “there’s a broad alignment forming around a climate policy platform that is both ambitious enough to address the problem and politically potent enough to unite all the left’s various interest groups.”

Roberts quotes Maggie Thomas, former campaign aide to Jay Inslee and Elizabeth Warren, now with the climate mobilization group Evergreen Action: “All of those people who ran for president … had a much more expanded vision on climate by the end of their campaigns than when they started,” and then offers sections entitled Net-zero emissions by 2050 is the new baseline, Republicans aren’t going to help, and Carbon pricing has been dethroned (we’ll have more on that in a bit), before unveiling his synopsis of this emerging Democratic climate alignment:

- Standards: “[E]lectricity, cars, and buildings together … make up close to two-thirds of US emissions. The core of any aggressive 10-year mobilization on climate must be to target them, not sideways through a carbon price, but directly, through sector-specific performance standards and incentives, to drive out the carbon as quickly as possible.” Details vary among various (former) candidates’ platforms and advocacy groups’ programs, Roberts, notes, “but there is a strong common core: performance standards and incentives for the three biggest emitting sectors, aimed at making rapid, substantial progress on emissions in the next 10 years [with] the ultimate vision a carbon-free electricity sector powering an electrified, emission-free vehicle fleet and building stock.”

- Investment: The idea of “large-scale public investment,” says Roberts, “is not new, but something about the moment — the rising danger of climate change, the growing influence of Sanders-style democratic socialism, the pent-up public need after decades of austerity politics — made it resonate.” “The investment ideas cover a wide range, e.g., rural electrification, universal broadband, long-distance electricity transmission, and electric vehicle charging infrastructure [though public transit goes unmentioned here], but the focus in all of them is supporting green industries, manufacturing, and research, and, above all, creating jobs.”

- Justice — “for unions, fossil fuel workers, and front-line communities,” per Roberts’ summary. “Putting justice first,” which the emergent alignment does, “represents the most notable shift in green thinking and strategy over the past decade,” in Roberts’ estimation. And I believe he’s right. Whereas “climate justice” has been construed primarily as remediation and protection for marginalized constituencies that are predominantly Indigenous or communities of color, it is now extended and broadened to encompass workers in obsolescent fossil-fuel industries, the regions burdened by energy extraction and processing, and under-employed people.

Is “Standards-Investment-Justice” reconcilable with CTC’s “Taxing Carbon and Wealth for a Green New Deal”?

While the Standards-Investment-Justice moniker is largely Roberts’ formulation, the idea it encapsulates has been in the air for a year or more and is now trending. It’s easy to see why. Performance standards are broadly accepted in the U.S., if not by Fox News mouthpieces then by an impressively broad spectrum from environmental groups to appliance manufacturers. (The standards rubric also includes state-level clean-electricity standards that many credit with priming the wind and solar power pumps for the past one or two decades.) Investment is newly resonant for the reasons Roberts notes, with credit also due Green New Deal proponents including the Sunrise Movement for their constant invocations of FDR’s presidency (minus the racist exclusions). Justice, a bedrock human ideal, here becomes a rubric to unite two factions that are vital yet have rarely been joined politically: the environmental justice left and the more traditional labor center.

“S-I-J” strikes us, then, as empowering and vital. But what about “P” for pricing — carbon pricing? Recall that Roberts dissed it, in the Carbon pricing has been dethroned section of his post. Here’s how he put it:

Carbon pricing — long treated as the sine qua non of serious climate policy — is no longer at the center of these discussions, or even particularly privileged in them. For one thing, there’s the political economy: Raising prices is unpopular, and raising prices enough, fast enough, to hit the 2050 [net-zero emissions] target will be an almost insuperable political challenge. Cap and trade is still in the reputational toilet. Carbon taxes never saw the bipartisan support their backers always promised. The politics of carbon pricing just don’t seem to be going anywhere.

Roberts is right on several counts: Carbon pricing is no longer centered in climate policy. Raising prices is politically difficult. Cap and trade is toxic. And carbon taxing has lacked bipartisan support since the 2009 Tea Party insurrection (the occasional Republican mild pats-on-the-back for token carbon taxes don’t really count).

But his insinuation that carbon pricing in isolation can’t get us to net-zero emissions by 2050 is a straw man; no carbon pricing advocate of any stature has posed it as a stand-alone measure for a long time. More importantly, the absence of bipartisan support shouldn’t disqualify carbon taxes from consideration by a Democratic White House and Congress, should that be the outcome of the November elections. With Democratic majorities, and assuming the newly Democratic Senate abolishes the filibuster, a meaningful carbon tax, e.g., one that begins at $15 or $20 per ton of CO2 and rises annually by $15 to reach $100 per ton within seven years, ought to be able to get through Congress and reach the White House.

Biden’s $2 Trillion Climate Plan

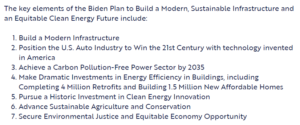

Yesterday, the Biden campaign released its climate plan. The Biden Plan To Build A Modern, Sustainable Infrastructure And An Equitable Clean Energy Future would invest $2 trillion over the next four years to build new infrastructure, boost clean energy, and repair and remediate communities historically damaged ecologically and socially by fossil fuel extraction and burning.

The Biden plan appears to embed carbon reduction in a broader framework of economic recovery, infrastructure revival, racial equity, and jobs — apt framing in light of the Depression that has enveloped the U.S. in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Trump administration’s largely business-as-usual stance, as well as the awakening of many Americans to the ongoing damage from persistent structural racism.

Release of the plan followed on the heels of the Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force’s policy recommendations on climate change issued last week (July 9), which in turn hewed fairly closely to the June recommendations of the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. The select committee’s “majority” report (from the Democratic conference), Solving the Climate Crisis: The Congressional Action Plan for a Clean Energy Economy and a Healthy and Just America, “calls on Congress to build a clean energy economy that values workers, centers environmental justice, and is prepared to meet the challenges of the climate crisis.”

Release of the plan followed on the heels of the Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force’s policy recommendations on climate change issued last week (July 9), which in turn hewed fairly closely to the June recommendations of the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. The select committee’s “majority” report (from the Democratic conference), Solving the Climate Crisis: The Congressional Action Plan for a Clean Energy Economy and a Healthy and Just America, “calls on Congress to build a clean energy economy that values workers, centers environmental justice, and is prepared to meet the challenges of the climate crisis.”

We’ve read the Biden Plan’s write-up of its seven key elements, shown above — U-C Santa Barbara poli sci professor and climate savant Leah Stokes has an excellent Twitter thread on it, by the way — and have seen nothing about, or even hinting at, carbon taxing or carbon pricing of any stripe. On the other hand, another part of the Biden Campaign’s climate page, Biden’s Year One Legislative Agenda on Climate Change, includes language suggesting support for pricing carbon emissions:

This enforcement mechanism [to achieve net-zero emissions no later than 2050] will be based on the principles that polluters must bear the full cost of the carbon pollution they are emitting and that our economy must achieve ambitious reductions in emissions economy-wide instead of having just a few sectors carry the burden of change. (emphasis added)

That said, sifting various iterations of the Biden campaign’s climate platform doesn’t feel particularly useful. Whatever climate legislation (and executive action) emerges from a Biden administration and Democratic Congress is likely to be determined more by the demands of the climate movement this year and next than by Biden campaign statement. The implication is that carbon tax advocates would do better educating fellow climate campaigners on the need for carbon taxing — and, of course, organizing for electoral change this summer and fall — than bemoaning the absence of carbon taxing from current climate discourse.

We give the last word to the Times’ David Leonhardt, whose July 10 column we drew on, above:

“If there is a single lesson of the current era of American politics, it’s that change can happen more quickly than we imagined.”

Lorna Salzman says

Two major unlearned lessons are evident, one taught by biologist Karin Mattis and the other by the makers of the film Planet of the Humans:

The most urgent crisis is Ecological Collapse: the collapse of planetary systems as a result of overpopulation, overconsumption, and loss of biodiversity.

The second is the stubborn refusal to acknowledge that a a massive Green New Deal requires continued exploitation of mineral and plant resources, energy inputs, and destruction of planetary habitats. The GND represents a continuation of the unsustainable economic growth model, rationalized by a commitment to equality. This precaution extends to renewable energy as well. A commitment to huge infrastructure projects that require large amounts of natural resources, energy and land is NOT a commitment to planetary survival or to social justice. Nature’s response to overexploitation is the same regardless of whether the objective is improving human lives or achieving equality and social justice. The absence of any consideration of natural systems’ response to continued economic growth will deal a fatal blow to any GND. The only sane alternative is to move to a steady state economy that foregoes economic growth and places human needs within rather than above those of nonhumans and planetary systems.

Chris Chidsey says

We have to focus on the per-capita dividend in a credible fee-and-dividend plan like HR763. I suggest the next iteration be titled “Equitable Advance and Carbon Fee” to emphasize that folks will have cash in advance of the fee to either invest in lower carbon technology or pay for their increased costs, and that it will be equitably distributed on a per capita basis to everyone. Politicians generally think they know better what to do with any fee than their constituents (see Macron and the Yellow Vests). It may take a President Biden who will not be running for reelection to take the larger view. Can we get Andrew Yang to persuade him?

Russell Lowes' says

The problem with HR 763 is that it trades away the ability of CO2 management under the Clean Air Act by the EPA. This sets a dangerous precedent for trading away our environmental laws. It also disables the law in relation to CO2 production. And some people think that polluting Industries will try to enjoin this with particulate regulation or anything else that is parallel to CO2 regulation, further disemboweling the Clean Air Act.

Chris Chidsey says

I don’t like the all aspects of the regulator pause. However, politics is the art of compromise for the greater good. There are some aspects of the pause that are actually good. Example: future CO2 emissions from electricity generation can very reasonably be traded for an increased cost of carbon in fuel. Not true for NOx, SOx, particular carbon, methane or chlorofluorocarbons. We need to hold the line in the next Congress and make sure these don’t sneak in. We should also look to get agriculatural and military fuels included. The CCL argument that the export exposure of Ag justifies the exclusion is weak. That’s what the border adjustment is for. Insist it be used — in fact trust that American Ag will insist it be used. As for the military, that’s what their budget is for but don’t let them avoid the incentive the tax provides to adopt least-cost alternatives to fossil fuels.

Christopher Ketcham says

There is zero mention in your piece of the central necessary component to any green, planet-friendly, carbon-neutral economy: downscaling. Less consumption, less mobility, less travel, less of every goddamn thing that we can take for granted as our material birthright. If you don’t make that point absolutely pivotal in any argument claiming to offer a climate solution, well I can’t take you seriously. Of course, downscaling is not salable to the spoiled rotten American public — which is exactly why Biden breathes not a word about it, nor does one hear anything about downscaling in the Green New Deal. As far as I’m concerned, it’s all just blowin smoke until we confront the monster in the room.

Drew Keeling says

@ C. Ketchum:

Your several points are well-taken, nonetheless there is probably no better single step towards systematic “downscaling” than a deliberately higher relative price for carbon fuels (e.g. carbon “fees and dividends” on a revenue-neutral basis, with direct or indirect equity and border adjustments).

Meanwhile, we need to be well-prepared (as was patently not the case with the 2016 election or in 2020 re Corona) for Biden choking and losing this coming November, and alternatively, for Biden and the DNC choking after winning next November, but also for a Democratic Party sweep that is -for once- not bungled or squandered.

Michael Aucott says

I heartily agree with your point that David Roberts’ criticism of a carbon price because it is not a cure-all is really a straw man argument. Clearly more must be done, but there is probably not a bigger and better first step to controlling carbon pollution than putting a price on it.

Andy R. says

There is another angle for carbon taxes–as a revenue support for needed green infrastructure/industrial policy. The fiscal support for decarbonizing investment that carbon taxes could enable could be dramatically expanded by using carbon tax proceeds to support bonding and other investment vehicles vs. simply direct dollar for dollar investments of proceeds. I would think as a source of revenue support for the SIJ agenda that a new look at carbon taxes would be welcomed. I do/still think the price (and political) signal that a carbon price would entail should not be fully discounted–that is as absurd as the opposite proposition–saying that a carbon tax can do all the necessary work by itself. Here I agree with McKibben that a carbon price signal might have been enough to do most of the work if it had been enacted while enough of a time horizon remained and before the last generation’s worth of investments in fossil infrastructure was sunk–like, say, around 1980 when Exxon was deep-sixing its own climate research. But while that counterfactual is perhaps of academic interest, the point is that now all useful policy tools should be deployed.