Note: A new (March 2021) CTC page, Carbon Pricing and Environmental Justice, summarizes this post and its Sept. 2020 predecessor, Environmental Justice, Borne Aloft by Carbon Pricing, and embeds them in a larger narrative about the environmental justice movement’s increasing turn against carbon pricing.

Mary Nichols’ candidacy to lead the US Environmental Protection Agency is over. Not so, the need to grapple with the profound mistrust of carbon pricing felt by many advocates for environmental justice.

Nichols, long-time California clean-air chief, was considered “a lock” to head the EPA, according to the New York Times, until 70 environmental justice and allied groups sent a strongly worded letter, excerpted at left, to the Biden-Harris transition team opposing her nomination. The new administration’s selection of North Carolina environmental quality secretary Michael Regan for the position was announced last week.

Excerpt from 70 groups’ Dec. 2 letter. Bold is from original, red is CTC’s emphasis. The link is to the Cushing analysis discussed in this post. Additional text criticizing cap-and-trade isn’t shown here.

Signatories (download the letter here, pdf) included national organizations Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, Food & Water Watch and Oil Change International, along with dozens of California groups and the umbrella California Environmental Justice Alliance.

A principal charge in the letter, and the one singled out by the Times and in other media accounts, was a claim that the carbon cap-and-trade program overseen by Nichols and the California Air Resources Board “perpetrates environmental racism [by] increas[ing] pollution hotspots for communities of color in California.”

That charge may be seen as a culmination of the deep suspicion with which many environmental justice advocates regard pollution taxes or cap-and-trade schemes (the two are often termed “market measures”) intended to cut carbon emissions.

I did my own grappling with this matter in a lengthy post here in September. I noted inter alia that “many activists recoil from carbon pricing’s implicit acquiescence to capitalist means of exchange that [appear to] commodify pollution” — language similar to the EJ letter’s charge that “market mechanisms … commodify the source of the climate crisis.”

Ironically, those who, like me, train an economic lens on the climate crisis regard the failure to price carbon emissions as a source of the climate crisis. And not just economists but the entire environmental community is united in demanding elimination of fossil fuel subsidies. Yet the ability to dump carbon pollution into the atmosphere for free is the biggest subsidy of all, and carbon taxes (or “charges”) uniquely diminish that subsidy.

Nevertheless, the sharper irony, addressed here, is that the cap-and-trade program that is being vilified for perpetrating environmental inequities appears in practice to be diminishing them.

Environmental Inequity and Pollution Hotspots

As recently as a decade ago, ground-level concentrations of deadly carbon “co-pollutants” — toxic particles and gaseous oxides — issued from industrial smokestacks in California were three to four times higher in disadvantaged communities than in more affluent and predominantly white locales. That result was derived in an analysis published earlier this year by two U-C Santa Barbara economists, ratifying what environmental justice campaigners from these communities have always understood.

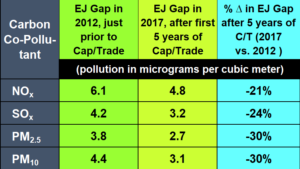

Truncated version of table from my Sept. 28 post. EJ Gap is difference in ambient air pollution between CA-codified “disadvantaged” zip codes and other locales. Blue column shows narrowing of gap.

Compounding this long-standing health assault, an early cap-and-trade program meant to curb smog in California (called Reclaim) was riven with escape clauses that, it is said, emboldened increases in pollution dumping onto minority communities from an enormous oil refinery — the state’s second largest — in Richmond, near San Francisco. The conviction was soon born that pricing of pollution, whether auctioned to polluters as tradeable emission permits (cap-and-trade) or charged directly (via pollution taxes), could never mitigate pollution inequities afflicting historically-burdened communities of color.

This belief grew and intensified across California, fueled by intersecting political and social currents and by research suggesting that a newer, more ambitious and less porous statewide carbon cap-and-trade program legislated in 2006 and put in place in 2013 by the California Air Resources Board was likewise concentrating emissions in minority communities. (A 2019 paper, California Climate Policies Serving Climate Justice, by Univ. of San Francisco Law Professor Alice Kaswan, is a useful guide to the state’s many laws addressing carbon emissions and environmental injustice.)

Must carbon pricing worsen hotspots?

The specter of “hotspots” is paramount in the Dec. 2 EJ letter and prominent in environmental justice expressions on pollution pricing. Yet the idea that polluters respond to charging for pollution by perpetuating or, worse, exacerbating toxic emissions in poor communities runs counter to almost everything we know (or believe we know) about how polluting enterprises actually operate.

A carbon tax, by its nature, exacts a cost for every missed opportunity to reduce carbon emissions. Carbon pricing makes every means — and there are literally billions at hand — of reducing carbon emissions more profitable, which is why devotees of carbon taxes find them so enticing.

The price incentive, we believe, gives individuals and especially companies new cost-effective means to pare their use of carbon fuels. (The same is true for carbon cap-and-trade programs, although there the cost is paid, somewhat indirectly, via the polluting company’s purchase of emission permits, and the price signal is found in the carbon-permit market.) Accordingly, a company that deliberately perpetuated toxic hot spots in disadvantaged communities would weaken its bottom line.

Consider an oil company that operates 10 refineries — 5 in minority communities, 5 in white locales. Under a carbon price, every new piece of equipment or procedure that reduces carbon emissions at any of the 10 reduces the company’s carbon tax tab (or its cap-and-trade expenses).

All 10 refineries will almost certainly undergo some change to lower their emissions. Logistical considerations or racial favoritism might conceivably lead the company to concentrate more of its reduction effort at its 5 white sites. But it strains credulity to posit that the minority sites will take on more emissions on account of the carbon price.

The reason? Carbon pricing is a unitary policy that applies equally to all emissions. Charging for emissions creates opportunities to cut emissions everywhere, simultaneously. The choice presented to headquarters isn’t to pit potential reductions from Refineries 1-5 against reductions from Refineries 6-10, but to max out on the new cost-cutting opportunities that the carbon price presents at Refineries 1 through 10 .

This schematic suggests that even community-neutral pricing policies — ones that lower total emissions without regard to where — will benefit disadvantaged communities in health terms. That is true even if the relative bias of disproportionate burdens on those communities isn’t specifically targeted, whether in the pricing design or in the use of the carbon-pricing revenues.

Keep in mind that the refineries or other large emitters that are most cost-effective to upgrade or downsize because of the carbon price will be those with the oldest, most-polluting equipment. To the extent that these are in poorer communities — a syndrome that the environmental justice movement has documented for decades — the emission reductions will be concentrated there as well.

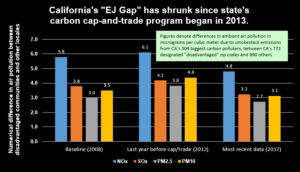

Graphic from my Sept. 28 post illustrates the narrowing in California’s “EJ” gap due to the state’s cap-and-trade program.

There is also the mathematical fact that equal percentage reductions across the board will bring the greatest absolute emission reductions where the baseline emissions are highest. If polluters are spewing 200 tons of pollution on your community but only 100 tons on mine, a 25% reduction everywhere will cut emissions in your back yard by 50 tons, vs. 25 tons in mine.

For the inequitable historic differential in pollution exposures to widen, there would have to be grossly lesser emission percentage reductions in minority areas. In the example above, the decrease in emissions in those areas would have to be held to just 25% while emissions elsewhere fell 50% or more.

A few such examples can probably be found in California, among the 300-plus emitters large enough to be covered by the state’s carbon cap-and-trade program. But so long as the overall cap is tightened each year while “offsets” and other loopholes are kept to a minimum, any increases will be far outweighed by reductions in other low-income communities of color.

A Startling Finding about California’s Carbon Cap-and-Trade Program

In early August, I learned of a new academic paper that, in its elegance and reach, appeared capable of singlehandedly untethering carbon pricing from the charge of environmental injustice. The paper is the one mentioned up front that found that just a decade ago, as a baseline, California’s disadvantaged communities suffered from far larger concentrations of carbon “co-pollutants” from industrial smokestacks, compared to whiter and more prosperous locales.

The person who collegially notified me of the paper was Lara Cushing, an epidemiologist (MA) and energy policy specialist (PhD). It was Prof. Cushing’s team whose research was cited in the letter to the Biden-Harris team charging that California’s carbon cap-and-trade program “perpetrates environmental racism.”

During the rest of August and most of September I pored over the academic paper, which was titled, “Do Environmental Markets Cause Environmental Injustice? Evidence from California’s Carbon Market.” I corresponded with its authors, members of U-C Santa Barbara’s economics department: PhD candidate Danae Hernandez-Cortes and Associate Prof. Kyle C. Meng. Their paper was complex and bursting with implications, and I wanted to be certain I understood it fully before writing it up. I circulated a draft story to a few environment-oriented outlets for publication or a news exclusive, eventually posting it myself to the Carbon Tax Center website on Sept. 28 as Environmental Justice, Borne Aloft by Carbon Pricing.

Hernandez-Cortes and Meng’s key finding, I explained, was this: From 2012 to 2017, the pollution disparity between disadvantaged and other communities in California fell an estimated 30 percent for particulates, 21 percent for nitrogen oxides and 24 percent for sulfur oxides. Moreover, the 21-30 percent drops in the state’s “EJ gap,” as they termed the disparity, was not merely concurrent with the cap-and-trade program, which CARB put into effect in 2013; it was “due to the policy” itself, according to the authors.

This finding differed diametrically from the conclusions of Prof. Cushing and her colleagues, and I was obliged to explain why. The account from my post is shown in the sidebar and summarized below:

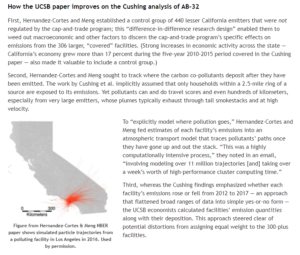

- To weed out macroeconomic and other extraneous factors and discern the cap-and-trade program’s specific effects on its “covered” facilities, Hernandez-Cortes and Meng included a comparison group of unregulated California emitters.

- Hernandez-Cortes and Meng traced the atmospheric paths taken by the pollutants once they left the smokestacks, via modeling, rather than assuming they landed in narrow bands nearby.

- Hernandez-Cortes and Meng based their before-and-after calculations on each facility’s actual emissions — a richer and more accurate approach than the earlier work’s up-or-down formulation.

Reactions to the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng Findings

My post highlighting the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng findings drew little comment (none from the environmental justice campaigners to whom I reached out) and very little press. The paper’s two mentions in the green press — in an October article in Grist, Cap and Trade-Offs, and in a November story in Yes! magazine, Can California’s Cap and Trade Actually Address Environmental Justice? — were cursory and largely dismissive.

For example, the Yes! article said that the 20% to 30% narrowing of the EJ gap applied only “in the areas where facilities were covered by the program,” whereas Hernandez-Cortes and Meng actually calculated the reductions across all of California’s 1,712 populated zip codes. The Grist story obfuscated Hernandez-Cortes and Meng’s statistically significant modeling of smokestack dispersions as reflecting only “a spread of outcomes of various likelihoods” — whatever that means.

One could almost intuit a wish to cling to the Cushing team’s negative conclusion about cap-and-trade’s outcomes, and thus to downplay Hernandez-Cortes and Meng’s ingenious analysis that had apparently upended it.

Finally, in late November, a substantive critique of the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng analysis appeared. It was posted by Danny Cullenward, a lecturer and affiliate fellow at Stanford Law School, and Katie Valenzuela, who formerly was policy and political director for the California Environmental Justice Alliance and co-chair of California’s AB 32 Environmental Justice Advisory Committee (AB 32 is the state’s 2006 umbrella climate law).

Yet the Cullenward-Valenzuela criticisms of Hernandez-Cortes – Meng appear to point to imperfections, not fatal flaws.

To wit: Hernandez-Cortes and Meng employed zip codes and not finer-grained census codes to compare EJ neighborhoods with other locales. Hernandez-Cortes – Meng drew smokestack data from the state’s 35 different regional air districts that, they say, “use 35 different methods for data collection.” Hernandez-Cortes and Meng didn’t adjust for possible confounding effects from California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, a companion climate measure that took effect during the period covered in their cap-and-trade analysis.

Notably, however, neither Cullenward-Valenzuela nor anyone else writing from an environmental justice perspective criticized the Cushing team’s analysis — the one bolstering the belief that the cap-and-trade program has deepened environmental inequities — for these same failings, let alone its more consequential shortcomings I enumerated in the preceding section. Nor did Cullenward and Valenzuela attempt to quantify how much, if at all, remedying the asserted shortcomings in the Hernandez-Cortes and Meng paper would weaken their findings.

Perhaps the weightiest criticism of Hernandez-Cortes – Meng from Cullenward and Valenzuela is their last, under the heading, “The question is not cap-and-trade versus nothing”:

If California had chosen a path of more prescriptive, direct emissions reductions … we would likely be seeing far more emissions reductions … and far more improvements for environmental justice communities than we’re seeing under the cap-and-trade program today. To say [the cap-and-trade program is] better than nothing ignores the fact that adopting a weak cap-and-trade program has led to prolonged and higher emissions in environmental justice communities than if California had adopted a stringent carbon pricing policy or relied instead on non-market mechanisms that would have been targeted at the pollution reductions our communities need.

That claim may well be true. It certainly resonates with me, an advocate since the late 1980s of straight-up carbon taxing rather than oblique and often loophole-plagued cap-and-trade approaches. But that’s not the question that Hernandez-Cortes and Meng tackled in their study, which was: On a statewide basis, has California’s cap-and-trade program widened or narrowed environmental inequities?

Though California EJ advocates insist that the cap-and-trade program has widened environmental inequities, no one has effectively rebutted the evidence marshaled by Hernandez-Cortes and Meng that it has actually narrowed them.

Possible Trouble Ahead

The scant attention accorded the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng paper has largely sidelined its meticulous and virtuosic treatment of the impact of California’s cap-and-trade program on environmental inequities. A result has been to let stand the accusation that the program’s sponsoring agency, the California Air Resources Board, has “perpetrated environmental racism.”

My concern here is not that that charge helped block CARB’s Mary Nichols from heading EPA, but with the possibility that its uncritical acceptance may impact national environmental and climate policies going forward.

The idea that carbon pricing cannot serve environmental justice may have been justified by systemic oppression, and it dovetails nicely with certain critiques of capitalism as being a willing handmaiden of inequity. But in its largest empirical test to date in the United States, that proposition has been shown highly questionable. Now, judging by its impact on Nichols, it threatens to block carbon pricing measures from consideration by the incoming Biden administration.

Getting meaningful climate legislation through a divided Congress will be difficult under any circumstances. The temptation will now be strong to jettison measures that might be opposed by advocates for racial justice and others on the left. Another New York Times story this month, this one showcasing president-elect Biden’s choices of Janet Yellen and Brian Deese for Treasury secretary and National Economic Council director, noted that carbon pricing “is fiercely opposed by both conservatives and some liberal groups.”

Carbon pricing, whether rendered through tradeable emission permits or straight up via carbon taxes, faces hurdles galore. Saddling it with unfounded criticisms, notwithstanding their deep wellsprings, appears more likely to compound environmental injustice rather than help overcome it.

Lorna Salzman says

It is regrettable that (presumed) progressive groups have adopted environmental policies scarcely different from those proposed by free marketeers and right wingers in defense of capitalism. The only difference is that social justice groups carry a flag of progressivism (often concealing the flag of socialism). In the case of both left and right, politics has overcome and now dictates energy policy and science itself. Equally regrettable is the failure of the left and social justice groups to see how they are not only undermining science and environmental activism, and indeed their allies in these sectors but setting a precedent for political struggles that, given their tenuous position and their radical political views, will almost certainly guarantee defeat.

khal spencer says

Once again, it seems that people want to make perfect the enemy of good. If the result is we have a fight between far left and far right and get nothing done, then that carbon will continue to be emitted and as we know, it has no boundaries. Truly, unfettered CO2 emissions are the biggest free ride we have as we continue to exploit are fossil fueled economy. Oh, well.

Harry M says

This leaves me thinking—and you do get to this—that the opposition is born out of fear that there will either be a market approach or a direct reduction + GND approach. It makes no sense that pricing would increase pollution specifically in communities of color. It seems more possible that carbon markets may increase environmental inequality, which is to say that while pollution goes down in fence-line communities across the board, the proportional drawdown is more significant in white and wealthier areas. This would still be a better outcome than no policy at all, and the research shows otherwise. Since the hard research seems to have been dismissed, your grafs explaining the logical implications of a 25% reduction may do more to clear this up.

Pricing doesn’t “commodify the source of the climate crisis,” but commodifies its elimination. I am almost done reading Kim Stanley Robinson’s “The Ministry for the Future.” I hope fellow ejs will read it and find themselves grappling with our baked-in animus towards carbon charges in the portions of the book depicting central banks issuing “carbon coins.” Of course, there is reason to be uncomfortable. I don’t love the idea of theoretically incentivizing the Supermajors to buy up reserves and forecast carbon burns so that world governments pay them to keep it in the ground. For this reason, it seems more in line with environmental justice, fiscal responsibility, and, certainly, a monetary policy that’s not a total head-scratcher to charge/tax/price/cap carbon burns out of existence (while ramping up renewable deployment).

Also interesting to note how popular CalEnviroScreen has become among the climate left. Demos, DFP, and likely many of the orgs that signed this letter appear to be advocating for the admin to implement this kind of mapping out of the WH and to take the cumulative impact of carbon burns and co-pollutants into account—the Clean Power Plan did not mandate cumulative impact be reviewed just advised states and agencies to review/disclose, right? Since pollution is worse in ej communities and because we want more climate investment dedicated towards them, it seems awfully logical that we’d map the pollution and, in addition to capping/pricing carbon, apply a logarithmic scale based on the magnitude of co-pollutants in a given area. This could help address the more complicated implication of pricing: The potential to exacerbate inequities as those with means are better able to adopt sustainable practices and will be relatively better off than those who cannot. You have led me to believe that massive investment + pricing is more likely to create an environment in which all can participate in the transition than a GND would alone.

Thanks for writing this up!

Rob Watson says

I continue to be confounded by the vitriol and one-sidedness with which advocates of both cap-and-trade and carbon taxes address each others’ approaches.

Surely there is room in the policy arena for *gasp* TWO complementary approaches to what is universally agreed to be the existential crisis of our species?

A fundamental tenet in market transformation is that regulatory push mechanisms (carbon taxes) and market pull mechanisms (cap-and-trade) complement one another by addressing different segments of the market, with carbon taxes raising the floor of performance and cap-and-trade allowing deeper penetration into the potential.

None of this is to excuse poorly designed markets or the challenges of passing not just one, but two politically fraught actions, but no one who truly understands the nature of the threat of unmanageable climate change to humanity should dismiss either option in favor of the other: both are necessary and neither is sufficient.

Michael P Totten says

Absolutely spot-on, Rob. I totally agree, and for decades was always puzzled that advocates for each policy didn’t fully embrace the other as an essential complement, rather than creating artificial tension to select one or the other camp.

Charles Komanoff says

Hi Rob — I’m surprised to see you bring up the issue of discord between cap/trade and carbon-tax advocates. It seems to me that advocates on both sides of that divide have pretty much declared a truce. These days we’re joined in calling for carbon pricing in *some* form. My post is evidence of that, with me, a carbon taxer, touting the environmental-equity benefits of California’s cap-and-trade program!

Tony says

It could be worth mentioning that there was a time in the past few years when the California EJ movement was supportive of carbon pricing in the form of SB775 which would have reformed the cap and trade program, in many ways to make it more like a carbon tax. Unfortunately that version of cap and trade did not pass, and instead a simple continuation with some give aways to the Western States Petroleum Association was passed (along side some beneficial EJ legislation). So, don’t assume that the EJ movement is uniformly against carbon pricing when they voice opposition to California’s specific existing program (and like any movement people and organizations all have their own nuanced positions).

For those who don’t live in California and participate in the state level politics it can be easy to adopt a simplified narrative where Jerry Brown is a glorious leader on climate and Mary Nichols has done nothing but good at CARB. But within California there is much frustration that such a progressive state has not been able to do more. One only need attend a few of CARB’s meetings about it’s climate scoping plan or CARB’s Environmental Justice Advisory Committee meetings to see the tension between climate and EJ activists and business interests in the state. Some of the concerns people have about Mary Nichols are about process and relationships as much as policies.

I encourage people wishing to comment on dynamics in California to reach out to a variety of people in California who are in the trenches working on these issues so they can get a nuanced picture of the dynamics in play.

Harry says

Good points

Sue Greer says

California’s cap and trade program is funding a training program for solar installers called Grid Alternatives.

Grid installs free solar panels on homes of low income residents. Grid’s training is open to everybody (including me). Grid in Los Angeles is most proud of training former inmates who have gone on to get jobs that pay well so they can move forward with their lives.

There is more than one kind of environmental justice.

Dr. A. Cannara says

“A carbon tax, by its nature, exacts a cost for every missed opportunity to reduce carbon emissions.” — this one sentence illustrates our problem — simple human bias. Firts, we don’t emit carbon, though soot isn’t great to disperse anyway. We emit atmospheric-warming gasses. Second, the CO2 tax is fine as defined, but we’re in need of fighting global warming. CO2 is just one part of our combustion-related GHG burden. Methane is now increasing and in now entering the positive-ffedback realm, where warming via CO2 & merthane leakage induces more methan leakage from natural sinks, such as tundra and seabeds.. Positive feedback means we’re no longer in control. A C-tax does nothing except to perhaps reduce the rate of runaway warming due to our GHG emissions. Why CCL folks hide from this is beyond me.

And why your web jockey makes us type in a grayed-out font if even more absurd, even discourteous.

Dick Smith says

Well said. I appreciate that you support your opinions with verifiable facts. However, I want to comment on a foundational question–not directed at you Charlie–but one which everyone needs to ask. Is my definition of “social justice” in the context of climate change definable and defensible? In my opinion, “America First” is an indefensible climate policy whether it’s coming from Donald Trump or the most comitted poverty fighter. And, America First is the unstated assumption that seems to unlerlie what to many progressives insist needs to be a pre-condition of dramatic federal action to reduce emissions.

I got involved in climate advocacy over a decade ago, because I could no longer stand by idly at the intersection of “social justice” and “climate science” and watch a terrible accident about to happen. My definition of social justice seems very different than some of the most outspoken critics of carbon pricing. My social-justice concern were that several billion people on this planet–the youngest (think, inter-generational justice) and poorest (think, differential impacts due to income inequality)–two groups who had done the least to cause the warming problem–would suffer first and worst from it. Overwhelmingly, these 1-2 billion people are people of color. And, overwhelmingly, they do not live in America.

Yet, when it comes to who caused the problem, no country has done more to create the 1.2C warming we’ve already experienced since the start of the industrial revolution around 1750 than America. It is certainly America First on GHG emissions. We can already see the impact at 1C, but it is nothing compared to the next 30 to 50 years as the planet warms to 2C, 3C and beyond.

The latest data from the UN High Commissioner on Refugees shows 70.8 million forcibly displaced globally from ALL causes–41.3 internally displaced and 25.9 cross-border refugees.

In 30 years, the World Bank says forced displacement from CLIMATE alone will be twice today’s total—or by 2050, 140 million in Asia, Africa and Latin America alone.

Within 50 years, the UN says CLIMATE-forced migration alone will be triple today’s level—somewhere between 200-250 million.

And, before the end of the century, a 2017 Columbia University study put future climate-forced migration as high as 1.2 billion people.

So, before you talk about dealing with social-justice issues in America as a pre-condition for cutting GHG emissions, please, think of the level of human suffering that any of those CLIMATE forced-displacement numbers represent—because it’s beyond my comprehension.

And, I’d like the loudest American voices linking climate-change legislation to “social justice” or “income inequality” here in America explain why their concerns should take precedence over concern about what’s happening—and going to happen—to those refugees abroad.

Because the world’s economists have a consensus that is as strong as the consensus among doctors that cigarettes cause strokes and lung disease–and as strong as the consenus among climate scientists that human activity is causing today’s warming. And, that consensus among economists is that carbon pricing is, BY FAR, the biggest tool in the emission-reductions toolbox. True, there are smart ways and dumb ways to price carbon. We need federal tax legislation that’s economy wide. We need to apply the tax as far upstream as possible–essentially at the first point of sale after it comes out of the ground (essentially, on mining and drilling companies or at the refinery) or across-our borders (tax import companies). And the tax revenue we collect should be given equally to all Americans–since it’s our commons–the atmosphere we all share equally–that burning their product pollutes. Sending carbon dividend checks in equal amounts to every American will reduce income-inequality. Overwhelmingly, poor people simply won’t see their energy costs (whether it’s the direct cost of gas at the pump or electricity at the meter) — or whether it’s the energy costs imbedded in all the other goods and services we buy–go up as much as richer people. Poor and middle income Americans simply don’t consume as much energy as wealthier Americans. So, distributing the tax revenue in equal shares (each check for the same dollar amount) means almost every poor family (say, the lowest 40% by income) will come out ahead, as will many middle-class families.

Carbon taxing and dividends will have other positive effects. Instead of killing jobs, a number of studies now show it will have a small, but positive, impact on job generation.

And, if the federal legislation needs to include one last feature–border adjustments on exports and imports that protect American jobs, businesses and farmer–not from ALL foreign competition–but from UNFAIR foreign competion. In the context of carbon taxes, that means imports from–or American exports to–countries without compable carbon pricing–especially for energy-intensive goods and services where the carbon-price differentials truly matter.

In the current congress, take a look at H.R. 763–and take a look at summary documents avaiilable on Citizens’ Climate Lobby’s website. The bill has 85 House co-sponsors–and the lead author, Rep. Deutch (D-FL) is committed to introducing the bill with bi-partisan support next session.

Peter Jacobsen says

Given that polluters are disproportionately concentrated in disadvantaged communities, then reducing pollution will disproportionately benefit disadvantaged communities.

There would have to be a pretty sinister conspiracy to have any other outcome. (Unless I’m missing something big.)

Daniel Marcin says

Excellent article!

Caroline Petti says

I count myself as among those who regret the aspersions some in the EJ community have cast on Mary Nichols and her commitment to environmental justice. I know from my own experience they could not be more wrong.

From 1989 – 2004, I worked in EPA’s Office of Air as a career employee (i.e., non-political). I worked on many environmental and public health issues over those years, but in the mid-1990’s (Clinton Administration) I was part of a Team of career employees working to support EPA Administrator Carol Browner and Assistant Administrator Mary Nichols in rulemakings to tighten air quality standards for ozone and particulate matter. EPA proposed a significant strengthening and, like many regulatory undertakings, the proposal was controversial.

Even within the Clinton Administration, itself, EPA’s proposal was controversial. There were many weeks of interagency meetings and debates over various aspects of the standards. Browner and Nichols fought aggressively to maintain EPA’s proposed level of stringency.

One particular OMB meeting stands out in my mind. The appropriate level of stringency and whether EJ should be integrated was the subject that afternoon. Several Cabinet Department representatives wanted a less stringent standard. They argued that it was inappropriate to integrate margins of safety aimed at EJ and vulnerable populations into a public health standard for a general population. Mary Nichols was adamant: the standards should account for and should be strong enough to protect those who may be more vulnerable or disproportionately affected. The debate got heated, but Nichols would not back down. Finally, Nichols simply stood up, grabbed up her briefing notebooks, and stormed out of the meeting with me and the EPA Team behind her. That was the end of that debate. And, in 1997 in what has been called one of the most important environmental decisions of the decade, EPA issued final standards for ozone and particulate matter.

Charles M. Fraser says

Not directly on issue but an example of spiteful, belligerent arrogance, I recently heard a Mercedes-Benz radio commercial announce Santa Claus’ trip across Siberia was now a week faster. Making a joke of something that’s certainly not funny. If we’re really geniuses no carbon brining vehicles would be produced and the ones on the road would be adequately subsidized and transitioned into electric vehicles. No?

Robert L. Bradley Jr. says

How do higher energy prices promote ‘environmental justice’? Pricing CO2 is a regressive tax, period. Trying to undo this with complicated finetuning in legislation can and should be avoided altogether.

Alfredo LdeR says

There will never be anything approaching a consensus that satisfies either leftist activists (trained to detect race or gender oppression where there is only gross income inequalities), or libertarians that demand the freedom to keep polluting (and destroying other people’s property), let alone both. Governments should ignore these vociferous minorities and proceed with decisive climate action, by going over the head of professional activists with 2-digit IQs, and appeal directly to people’s pockets with the Fee-and-Dividend proposed by the Citizen’s Climate Lobby. If politicos can’t understand this, they are just utterly incompetent.