Four states — Pennsylvania, Montana, Utah and Wyoming — have counties named Carbon, after their wealth-generating coal deposits. The last, in the south-central part of the nation’s least populous state but, by some measures, its windiest, is hosting construction of a giant wind farm called the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project — 700 wind turbines that within a few years will generate a combined 3,000 MW.

An image from the carbonwy.com home page. The wind turbines are best glimpsed by looking right to left.

The transition to wind of any county named for coal is bound to conjure both irony and poetry, a dynamic captured in a resonant photo-essay in today’s New York Times, Carbon County, Wyoming, Knows Which Way the Wind Is Blowing. (After we posted, the Times changed its headline to the anodyne “Wyoming Coal Country Pivots, Reluctantly, to Wind Farms.”)

For the Carbon Tax Center, the change is extra-delicious. More than 40 years ago, I toured a power plant and strip mine at the northern end of the region’s massive Powder River Basin, in Colstrip, Montana, before a backpacking trip deep into Wyoming’s Big Horn and Wind River mountain ranges. I wondered if the Northern Rockies would ever evolve from coal mining to wind harvesting, a question I put into a post here, A Struggling Wyoming Is Slow to Embrace Its Renewable Future, in 2016.

Now, at last, that embrace is gathering force. Last year, wind turbines in Wyoming generated 5,143,000 megawatt-hours of electricity, 20 percent more than in 2019, though less than Texas, Iowa and 14 other states. The Chokecherry and Sierra Madre project will add around 9,000,000 MWh, assuming the turbines spin the equivalent of full speed for one-third of the time. Other projects are expected to bring the state’s total to 27,000,000 MWh by 2029.

What’s driving the transition? Not a carbon tax, since neither the U.S. nor any coal-consuming state has one. And not federal policies. The long-standing production tax credit for renewables, though slightly shrunk last year, still grants wind developers $18 for each megawatt-hour their projects produce.

Rather, energy-efficiency gains that have flattened U.S. demand for electricity, along with an inability to cut operating costs, have handed coal-fired plants the short straw in today’s power-generation zero-sum game. When one source’s share goes up, another’s goes down. Meanwhile, wind turbines grow ever-larger, more powerful and more reliable, bringing down their costs. And developers have gotten savvier about obtaining permits and negotiating deals.

None of this seems lost on Terry Weickum, the 68-year-old mayor of Rawlins, the seat of Carbon County, whom the Times portrays as the embodiment of every wind energy paradox. The permitting and taxing guidelines that he wrote as head of the county’s wind task force helped unlock the state’s wind siting gridlock; but that displeased other, pro-coal county commissioners, costing him his county post. Like many of his neighbors, Weickum is said to disparage concerns over climate change and to “disapprove of the way the glossy turbines interrupt the emptiness of the sagebrush-spotted landscape.” Nonetheless he went to bat for wind power as a way to save Rawlins from the ghost-town fate that traditionally has befallen towns in the hardscrabble west that could neither keep up nor reinvent themselves.

None of this seems lost on Terry Weickum, the 68-year-old mayor of Rawlins, the seat of Carbon County, whom the Times portrays as the embodiment of every wind energy paradox. The permitting and taxing guidelines that he wrote as head of the county’s wind task force helped unlock the state’s wind siting gridlock; but that displeased other, pro-coal county commissioners, costing him his county post. Like many of his neighbors, Weickum is said to disparage concerns over climate change and to “disapprove of the way the glossy turbines interrupt the emptiness of the sagebrush-spotted landscape.” Nonetheless he went to bat for wind power as a way to save Rawlins from the ghost-town fate that traditionally has befallen towns in the hardscrabble west that could neither keep up nor reinvent themselves.

“If it wasn’t for wind farms, [Carbon County and Rawlins] would be in terrible shape,” Weickum told the Times. Wind is also now a godsend for Weickum’s printing and sign-making business. Last year it took in nothing from coal-mining companies but garnered $150,000 of business from wind companies.

In another sign of wind power’s evolution in Wyoming, debate could be starting to shift from “Wind yes or no?” to “How much should we tax wind power?,” judging from a story from Wyoming Public Media, Proposal To Raise Wind Tax Dies Again In Committee (hat tip to the Times for the link).

Last December, the legislature’s Joint Revenue Committee voted down a proposed doubling in the state’s wind tax royalty, to $2 per MWh from the current $1. The debate was earnest and thoughtful, as reported by WPM. A businessman from Lander, in the western part of the state, who opposes wind power and supported the increase, testified “There’s a fear that by imposing realistic taxes on renewable energy, producers will go elsewhere. But that argument supposes that citizens in other states will not value their contributions to production as lovingly as we do in Wyoming.”

On the anti-taxing side, a number of local government officials, ranchers and residents argued in tandem with the wind-energy companies that even at just $1/MWh, the royalty payments have been “a bright revenue spot for a state used to a boom-bust cycle,” as WPM put it, but that raising it risked branding the state as unreliable and driving wind developers elsewhere.

Image from Power Company of Wyoming LLC, developer of the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre project in Carbon County, WY.

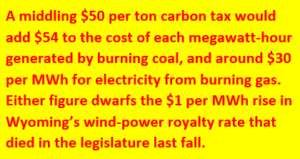

CTC aligns with Wyoming’s higher-tax folks. Yet it’s safe to say that no one at the hearing brought up the possibility that a national carbon tax could create room to raise Wyoming’s royalty rate without hamstringing the state’s fledgling wind sector. The numbers are intriguing. A middling carbon tax of $50 per ton of CO2 — more than the token $20 rate that occasionally escapes Exxon’s lips, but less than the triple-digit charge that CTC and others eye as the needed level to reach by the end of this decade — would add a hefty $54 to the cost of each megawatt-hour generated by burning coal. The effective tax on natural gas-fired generation would be less, just $22.50, though with an ancillary tax on methane emissions that would probably rise to around $30 per MWh. Either figure dwarfs the $1 a MWh increase that died in the legislature.

Such carbon-tax-driven increases in the merchant price of gas- and coal-fired electricity, which still accounted for nearly 60 percent of U.S. electricity last year, would give cover for Wyoming (and other states) to raise wind-power royalty rates by much more than a dollar per megawatt-hour. And while asking Wyoming’s hard-right Senators John Barrasso and Cynthia Lummis and its lone Rep. Liz Cheney to join the carbon-tax camp is surely a fool’s errand — coal mining still provides more employment than wind energy in Wyoming — the transformative power of carbon taxing is something Wyomingites may want to bear in mind as they continue their state’s transition from carbon to wind.

In the meantime, the rest of us would do well to ponder what Wyoming state senator Cale Case, an opponent of rapid wind development in his state (and a proponent of raising the royalty fee), told the Times: “This is one of the largest undeveloped places in the United States. There’s a pure existence value on its own to see what the early people saw, what the pioneers saw, just to be able to breathe.”

Amen. And while it’s true that any sentiments in the last century against turning Wyoming into the nation’s coal colony went unheeded, that doesn’t lessen the fact that even machines that magically turn air into power can’t be invisible.

Note: Calculations translating $50/ton carbon tax to $ per MWh assume 2.16 lb of CO2 per coal-fired kWh (heat rate = 10,080 Btu/kWh) and 0.90 lb for natural gas (assuming combined-cycle generation with heat rate = 7,658).

Peter Jacobsen says

Looking into open pit coal mines doesn’t generate this thinking: “This is one of the largest undeveloped places in the United States. There’s a pure existence value on its own to see what the early people saw, what the pioneers saw, just to be able to breathe.”

Using Earth, I measure Peabody’s North Antelope Rochelle mine 15 mile by 9 miles, or 45 square miles.