Switzerland voted on Sunday to repeal a package of carbon emissions regulations that included rises in carbon fees passed by parliament with a two-thirds majority last fall. The vote was 51.6% to repeal vs. 48.4% to retain the “new CO2 law.”

Where I live, the June 13 election consisted solely of yes or no choices on eleven propositions: three local, three cantonal level, and five national. The CO2 referendum results stole the show; reactions of pundits and the public ranged from shocked consternation to surprised delight. Front pages and home pages spoke of a “political earthquake,” the “worst-ever personal defeat” for the environmental minister, an “electoral watershed,” and Swiss climate policy “turned into ruins.”

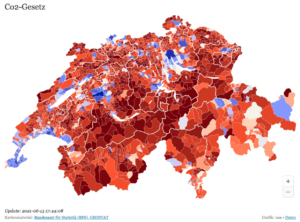

“CO2 Law” vote mapped by community, with blue denoting pro, red denoting anti, and deeper colors denoting bigger margins.

Switzerland takes climate change seriously. The small, mountainous country (population 8.6 million; area 15,940 square miles, around twice the size of New Jersey) believes it has already experienced greater climate change impacts than elsewhere in Europe, with the storied and iconic glaciers of the Swiss Alps dwindling visibly. Also important is Switzerland’s long and often profitable experience as a neutral facilitator and go-between in international diplomacy, its successful bid to host the Biden-Putin summit today being a case in point.

Carbon pricing has been gradually phased into Swiss energy and infrastructure policies since the late 1990s, linked with other carbon-reducing incentives, offsets, subsidies, regulations and emission trading provisos. Fees on petroleum fuels are tied to Paris Agreement targets and de facto conformity with various European Union rules.

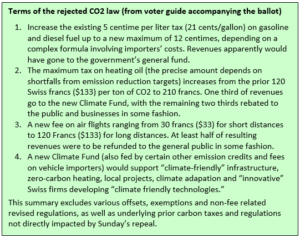

According to an analysis by the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (“NZZ”), the country’s effective carbon tax averages around $100 per ton of CO2, which would make it the world’s second highest, trailing only Sweden. The new (but now rejected) law would have raised that to as much as $200 per ton by 2030, according to NZZ. Proceeds from the increased carbon fees, along with the new levies on air travel, would have been split with roughly two-thirds of the revenues providing per capita rebates to Swiss taxpayers and the remaining one-third allotted to a new general-purpose “climate fund” (see text box below).

No subtlety in this “anti” postcard, and that’s the point. Driving only for the rich? Flying only for the rich? Left CO2 Law, NO!

The new climate fund was a centerpiece of the parliamentary compromise producing the new CO2 law, itself partly a response to the “Green wave” in Switzerland’s 2019 parliamentary elections, following the Greta Thunberg-inspired “school strikes for climate.” In 2019 the two Swiss Green parties more than doubled their parliamentary seats to a combined total of over 20%.

The climate fund helped leverage that mandate into two-thirds overall approval for the new CO2 law, but the planned fund later became a useful tool for the one political party not part of that deal: the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (Schweizerische Volkspartei). The SVP decided to wage a referendum campaign against the CO2 law, basing its opposition on the specter of rising taxes and regulations and potential misuse of the climate fund.

What went wrong?

There is no shortage of explanations for how a 2/3 parliamentary majority shrank to a 48% minority in barely nine months. In hindsight, it’s safe to say that the political-and-business-establishment-supported parliamentary coalition favoring stronger carbon emissions reduction was shaky and tepid. It failed at leading an effective campaign, as Green-Liberal Party head Jürg Grossen admitted after Sunday’s vote.

Warm, fuzzy, and oh so detailed: A mailer from the “pro” forces called climate protection “The way of Switzerland.”

Supporters of carbon taxation failed to communicate its advantages, he added, giving the example that only a minority of Swiss voters realize that higher heating oil taxes have been reducing their health insurance premiums for a decade or more. The new CO2 law was often seen as over-engineered and bureaucratic and was easily labeled as “too much” and “too expensive.” By one reckoning, as many as 15% of Green and a quarter of left-leaning Social Democrat voters drifted to the No side.

In contrast, opponents ran a tight, focused, aggressive campaign. Their campaign ads applied worst-case scenarios wholesale to supposed effects of the CO2 law: families would be “burdened,” renters and farmers “gouged,” and heating oil “practically banned.” A 12 centime per liter maximum hike in the gasoline tax, equivalent to 42 cents per gallon and amounting to about 18% of current overall gas taxes, and 8% of current all-in price, would mean that “only the rich” could “afford” to drive cars, etc.

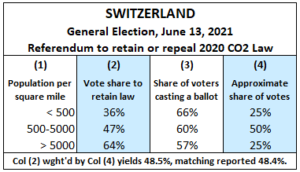

The antis’ bottom-line bullet points were misleading but crisp: the increased taxes were expensive, pointless, unfair. Proponents’ posters exuded warm fuzzy feelings about brighter days for the elderly and for children and, pointedly, appealed neither to resentment nor fear. Employers, employees, officials were shown as happy with the CO2 law, and therefore all pitching in to help out. The nearly 10-point difference between urban and rural turnouts (see table below) attests to which side’s approach best energized voter turnout.

A “new” urban-rural divide

The Swiss climate policy reset came as a surprise in part because it seemed at first blush to have developed off the usual political “radar screens,” as if by accident or happenstance. With the backing of two-thirds of the Swiss Parliament for the new CO2 law last September, the leaders of the center and left parties behind the law (i.e., all the major parties except the SVP) assumed there was more than sufficient popular support for it to withstand a referendum challenge. They miscalculated.

An American-style, red-blue political map, displayed during online tracking of Swiss afternoon election day returns reporting, revealed an unexpectedly stark pattern (see map above).

Of some 2,500 Swiss Gemeinde (communities), nearly every pro-climate policy blue patch last Sunday was a city or urban community of some kind, while remaining patches were almost all anti-CO2 law shades of red. Even cosmopolitan rural pockets such as the international resorts of Zermatt, Grindelwald and St. Moritz voted No. Their resident hotel, restaurant, and ski lift operators apparently felt more in tune with farmers, construction workers and delivery truck drivers from less gilded surrounding areas.

To be sure, some observers did notice aspects of this political shift before election day. But dots were unconnected and potential impacts discounted. Traveling the countryside in the weeks before the election, the head of the Swiss Farmers Association says he was astonished that “every remote hamlet” of rural Switzerland had posters up opposing the “leftist” CO2 law and arguing for its rejection by voters.

To be sure, some observers did notice aspects of this political shift before election day. But dots were unconnected and potential impacts discounted. Traveling the countryside in the weeks before the election, the head of the Swiss Farmers Association says he was astonished that “every remote hamlet” of rural Switzerland had posters up opposing the “leftist” CO2 law and arguing for its rejection by voters.

Monday’s front-page lead story of Tages-Anzeiger had this to say:

This Super Sunday surprise has revealed two opposing halves of Switzerland, that have failed to understand each other and been talking past each other. It is startling that things can come to such a disengagement in a culture that values the small-scale and local.

The table suggests an American-like heartland vs. metro divide. A Tages-Anzeiger election day exit poll reported similarly that urban voters averaged 60% pro CO2 law, and rural voters 60% anti.

Tabular simplification of red-blue map above.

What’s next for Switzerland’s carbon pricing and climate protection?

A smorgasbord of suggestions has appeared and local Swiss factors will shape future actions. Note, however, a near complete absence of claims that climate science is a fraud or even “disputed.” No Swiss politician is tweeting that global warming is a Chinese hoax. Coronavirus or vaccines may be doubted by some, but glaciers really are melting, Sahara desert sand has at times blown across to the north side of the Alps, 100 year floods are coming more like every decade, wildfires can now break out in April, etc.

The absence of climate science denial adds force to the demands of many non-SVP politicians that once the SVP finishes toasting the cancellation of the increased carbon emissions pricing, it will be time for it to tell the country how it proposes to address decarbonization and fulfill Switzerland’s Paris Agreement promises. How the SVP will respond is another matter.

Sunday’s repeal leaves prior pre-existing laws and carbon fee regulations in place, including possible extensions and/or rate-raising. Environment minister Simonetta Sommaruga summed up the situation by insisting that Switzerland “has not voted against climate protection, but only against one particular law.”

Drew Keeling is an independent researcher based in Switzerland.