Someone chose an inopportune time to beat up on carbon taxing’s fee-and-dividend variant. Not U-C Santa Barbara political scientist Mitto Mildenberger, whose paper, Limited impacts of carbon tax rebate programmes on public support for carbon pricing, co-authored with scholars from Montreal, Vancouver and Bern (Switzerland), appeared this week in the prestigious journal, Nature Climate Change. No, I mean iconoclast blogger David Roberts, who used Mildenberger’s provocative paper as a launching pad to again dunk on carbon pricing and people who still hold out hope for it.

Roberts’ post, Do dividends make carbon taxes more popular? Apparently not., published on Monday on his Volts platform, gets off on the wrong foot right away, claiming:

Economists have long insisted that pricing carbon is the most efficient way to reduce greenhouse gases. For years, they hijacked the climate discourse, with untold money and effort put behind proposals for various increasingly baroque pricing schemes, to very little effect. (emphasis added)

Roberts may be right about efficiency and economists, but his description doesn’t fit climate hawks like Citizens Climate Lobby and Carbon Tax Center. We place our chips on carbon taxes not on account of their economic efficiency but because of their unrivaled potential to slash carbon emissions quickly in the U.S. — and also their global portability.

The meat of Mildenberger’s paper and Roberts’ post, distilled in their respective titles, is that in the only two countries with some form of fee-and-dividend carbon pricing, not just public support but basic awareness of the programs, particularly the dividends themselves, is middling at best.

We think this “finding” is both questionable and beside the point. Let’s take a close look at each of those countries: Switzerland and Canada.

Switzerland

Official Swiss notice of this year’s carbon dividend. At the current 1.09 exchange rate, 88.20 CHF = $96.14.

Switzerland’s carbon tax began in 2008 and reached its current level of 96 Swiss francs per metric ton in 2018. Converting metrics and currencies, that equates to $95 per ton of CO2, the kind of level that carbon taxers dream about. According to CTC’s carbon tax model, if the U.S. next year started a $15/ton carbon tax and ramped it up to reach $95 in 2030, emissions in that year would be 33% less than in 2005, taking us 2/3 of the way to the Biden target of halving 2005 emissions in 2030.

Not only that, a U.S. carbon tax at the Swiss level of $95 a ton would generate a carbon dividend in 2030 of $1,500 per person, even allowing for reduced emissions and a larger population and equal shares for children. Surely, a $1,500 carbon check — or, if you prefer (and we do) 12 monthly carbon dividends of $125 per person — would translate into strong and rising popularity, especially considering that a majority of people and households would be expending less than those amounts in increased direct and indirect energy costs.

That’s the straw man. The reality is that Switzerland’s $95/ton (U.S.) carbon tax will deliver only $96 in per-person dividends for the entire year. (See document at left, downloadable here.) That’s less than one month’s worth of what U.S. residents would receive under a full fee-and-dividend scheme for a Swiss-level $95 carbon tax. In that light, it should be no surprise that Mildenberger and his co-authors didn’t find residents of Geneva or Zurich dancing in the streets over their carbon dividends. In U.S. terms, Swiss residents’ 2022 carbon tax dividend is what Americans would get in 2030 from a piddling carbon tax of $5.50 per ton of CO2.

Why the discrepancy? Why is Switzerland’s carbon dividend only 1/15 as great as what a U.S. dividend would be from a carbon fee of the same level?

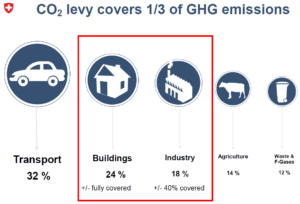

Excerpt from Switzerland Federal Office for the Environment document, “The Swiss Approach to Carbon Pricing,” May 2021.

There are four big reasons. First, Switzerland’s energy consumption is far less per capita than that of the United States. Second, hydro-electricity rather than carbon-based fuels like coal and methane powers the country’s grid. Third, the Swiss carbon tax exempts transport and agriculture and more than half of Swiss industry (see graphic at right; full document here). Fourth, part of the tax revenue is siphoned off by businesses before the dividends get calculated.

No wonder, then, that Switzerland’s carbon dividend is so meager. Consider further that, as Mildenberger et al. point out, “Citizens receive their rebates as a discount on their health insurance premiums, with annual notifications about this monthly benefit through health insurance forms.”

Annual notifications through health insurance forms. This is reasonable, even enlightened, public policy. It’s also almost diabolically designed to obfuscate the dividend side of the carbon fee coin.

Canada

Canada’s carbon tax is far more complicated than Switzerland’s. When we last updated CTC’s Canada page, in March 2011, we characterized carbon pricing in the country’s 13 provinces as follows:

- Six provinces, including Ontario and Alberta, were covered by the federal pricing scheme that would reach $50/tonne in 2023 — around $36/ton in U.S. terms — and then ramp up sharply to $170/tonne by 2030.

- Four were deploying their own carbon tax, led by British Columbia, which inaugurated the Western Hemisphere’s first meaningful carbon tax in 2008.

- Quebec and Nova Scotia were part of a two-country carbon cap-and-trade program that is anchored by California.

- New Brunswick employed an output-based carbon pricing system.

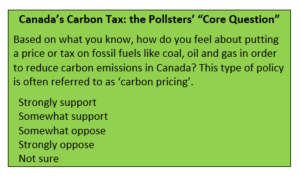

Wording courtesy of UCSB Prof. Matto Mildenberger, lead author of the Nature Climate Journal article discussed here.

Given this patch-quilt, as well as the novelty of carbon pricing in most of Canada, it seems to us unsurprising that polling that commenced in February 2019 (and extended through May 2020, with five “waves” in all) would yield the mixed results reported in the Midenberger paper: upticks in two provinces, Ontario and British Columbia, and downturns in the other three, Quebec, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The “core question” asked in the Canada polling, as described by lead author Mildenberger, who graciously shared it with us yesterday via email, is shown at left. The language is neutral, perhaps to a fault. It offered no affirmative spin, such as “Canada recently began taxing fossil fuels in order to protect the climate, with the money rebated in ways that will help households get ahead financially.” That kind of favorable tilt could perhaps be justified as necessary to counter the negative vibe surrounding taxation generally.

To be sure, that negative vibe is precisely what drives pundits like Roberts to deride carbon taxing, as he did in the second and third paragraphs of his post:

Over time, political experience with carbon taxes has highlighted a truth that should have been obvious long ago: carbon taxes are taxes, and people don’t like taxes. People don’t like paying more money for stuff.

More broadly, carbon taxes are an almost perfectly terrible policy from the perspective of political economy. They make costs visible to everyone, while the benefits are diffuse and indirect. They create many enemies, but have almost no support outside the climate movement itself. All the political intensity is with opponents.

We get it. We know full well the albatross that taxation always bears. But we also know that taxes on “bads” have been enacted into law. The U.S. government taxes cigarettes, as does every state. New York City taxes grocery bags, and Philadelphia and Berkeley, CA tax sugary soft drinks.

Obviously, taxing something as supercharged financially and culturally as fossil fuels is a much heavier lift, as evidenced by the absence of explicit carbon taxing anywhere in the fifty states. (We exclude federal and state motor fuel taxes, due to their tie-in to roads rather than health or climate; we also exclude New York State’s Petroleum Business Tax, though its support of NYC metro-area transit perhaps merits an honorable mention; conversely, New York City’s congestion pricing program, now scheduled to begin in 2023, will create a strong template for carbon taxing, as we’ve pointed out many times, including in The Nation magazine in 2019.)

So yes, carbon taxing — not fig-leaf $20/ton-and-no-higher carbon taxing a la Exxon or the occasional Republican, but a levy rising steadily to triple digits before 2030 — is hard stuff. But so is just about every other decarbonization policy or program, especially if done at scale.

Well-heeled NIMBY’s have whittled down wind projects for years; now, so too may supply-chain problems. Rooftop solar endures pushback not just from utilities and their high-wage unions but also from concerns that lower-income residents could gett stuck with higher utility bills. Only splinters of President Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which wasn’t going to be able to deliver its promised 50% cut in emission by 2030 anyway, will pass, thanks to one or two Democratic senators and 50 Republicans. Even the push to electrify everything may find its vaunted carbon benefits a good deal less potent than advocates imagine, an issue we intend to explore in a future post.

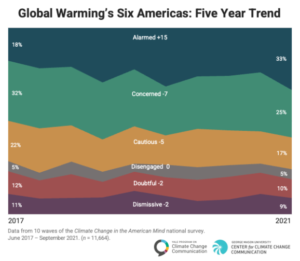

A record one-third of Americans in the latest “Global Warming’s Six Americas” are “alarmed” by climate change.

Still, though, the biggest misdirection in the Mildenberger et al. paper and the Roberts post may be their fretting over public opinion in the first place. The public doesn’t have to love carbon fee-and-dividend. It simply needs to embolden political leadership that will enact it (and the raft of complementary policies) into law and ensure that the fee, which shouldn’t be set too high to start, can keep rising over time.

Public opinion increasingly supports climate action, not tepidly but “with alarm,” as the latest Yale – George Mason opinion survey of “Global Warming’s Six Americas” attests (see graphic at right, and more detailed treatment with link here). It’s past time for carbon pricing naysayers to throw off their ideological blinders and get behind policies that can pass and deliver.

PS to David Roberts: Contrary to your Volts post, fee-and-dividend did not “los[e] badly in a public referendum in 2016.” What went down to defeat in Washington state was a sales tax swap of the carbon revenues, necessitated by the state’s constitutional prohibition against dividend-type state tax treatments. And what doomed the proposal was opposition from climate hawks who took umbrage at being leapfrogged politically, and in revenge brought in lefty heavy hitters to slime the measure. But that’s another story.

Huge hat tip to friend of CTC Drew Keeling for Swiss materials and perspective. Drew’s most recent Carbon Tax Center post, Rural disgruntlement, pro-climate complacency sink expansion of Swiss carbon tax, appeared in June 2021.

Peter Joseph says

Thank you, Charles, for this very cogent analysis proving the GIGO principle.

Ray Welch says

This “study” seemed iffy from the get-go. Two data points do not a trend make. Also, it seemed obvious that some complexities were being elided. Thanks for elucidating the relevant details.

James Handley says

Roberts complains that economists care too much about cost-effective climate policy. But cost-effective also means climate-effective. I appreciate the title (and content) of Gib Metcalf’s book, “Paying For Pollution, Why A Carbon Tax is Good For America.” https://carbontaxnetwork.org/2019/02/03/book-review-paying-for-pollution-why-a-carbon-tax-is-good-for-america/

Alas, too many advocates obscure this fundamental strength of pollution taxes with fuzzy terminology and opaque policy. “Fee & dividend” hardly screams out “effective climate policy,” and “carbon pricing” is usually a euphemism for cap, trade & offset, whose name and design obscure the principle that effective climate policy requires polluters to pay. Who would guess that “Citizens for Carbon Dividends” is a climate org that supports the polluter pays principle?

Instead of hiding the unsurpassed strength of pollution taxes to combat the climate crisis, isn’t it long past time to start selling their strongest point? Say it loud and clear: Tax Climate Pollution!

James Handley says

P.S. Roberts claims carbon tax advocates are politically naive because taxes are just an impossible sell It turns out the pollution taxes are different. A recent survey published last month in Nature Communications found strong support for carbon taxes when information is provided about how much they reduce emissions and when tax revenue is spent on climate projects. See, “Carbon tax acceptability with information provision and mixed revenue uses.” https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-27380-8

Trudy Heller says

Interesting that the author reports Canadians divided, with Liberals supporting carbon pricing more than Conservatives. In the USA I believe it is the opposite. Conservative groups, like RepublicEn, Young Conservatives for Carbon Dividends, and now even the US Chamber of Commerce, advocate a “price on carbon” as a “market-based solution” to the climate crisis.

Robert Nagle says

In west Houston where I live, carbon pricing will make a huge difference. Here customers choose their power provider on the free market. They typically renew their energy plans every year. (They often use powertochoose.org to help them). But the price for renewable energy plans for residential customers is the same as the price for dirty fuels. Sometimes in fact the price for renewable plans is cheaper. It would be easy and painless for consumers here to switch quickly. If prices for dirty power plans increased, consumers would switch quickly.