Prices of gasoline and other petroleum products as well as methane (“natural”) gas were already unusually high in the U.S. before Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24. Less than two weeks on (March 9), they’re at levels not seen since 2008, prompting the usual motorist grumbling but also creating hardship for squeezed families. Here we shed light on four key questions:

- Is the backlash against high pump prices an argument against pursuing carbon taxes?

- How big a hit are U.S. consumers taking from the higher fuel prices?

- Is demand for gasoline sensitive to the price at the pump? If so, how much?

- How much could the U.S. cut oil demand, right away?

Q1: Is the backlash against high pump prices an argument against pursuing carbon taxes?

A1: No.

Joseph Majkut explains:

Things that are not the same:

A carbon price with transfers to households and oil price increases from supply shocks.— Joseph Majkut (@JosephMajkut) March 8, 2022

Let’s unpack the tweet from Majkut, former Senate staffer and Niskanen Center climate specialist now with the national security think tank CSIS.

Supply shocks, like today’s, exact monies from businesses and consumers and transfer it to the oil industry — extractors, refiners, traders, brokers, insurers.

Carbon pricing, in contrast, is imposed by governments. And though it leads, deliberately, to higher fuel prices, the tax monies are collected by government and become revenues that can be used for public purposes. The “canonical” outlet — the one increasingly urged by carbon-pricing advocates in NGO’s and government — is to distribute (“transfer,” in Majkut’s phrase) the revenues as equal “dividends” to households.

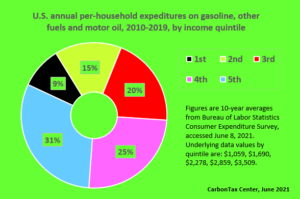

The wealthiest U.S. household quintile spends 3.3 times as much on gasoline as the poorest. So dividing the revenue pie equally among all households yields a big net plus to lower-income families.

This fee-and-dividend approach, pioneered by Citizens Climate Lobby, is income-progressive because lower-income households spend fewer dollars on fuels (directly plus indirectly) than wealthier households. Fuel price shocks, on the other hand, are regressive because lower-income households spend a larger share of their budgets on fuel.

If these points appear contradictory, please study the donut chart at right, or consult our page, Ensuring Equity. It’s the dividend that makes carbon pricing progressive, and the lack of a dividend that makes oil shocks regressive.

Q2: How big a hit are U.S. consumers taking from the higher fuel prices?

A2: A pretty big one, though it’s probably transitory.

In 2019, the last pre-pandemic year, the U.S. consumed 32.2 quads of methane (“natural”) gas and 43.5 quads of petroleum products. (A quad, or quadrillion Btu, is a standard metric for characterizing enormous energy quantities.)

Methane gas is used for power generation, heating of homes and commercial buildings, and as process heat for industry. Petroleum products encompass not just gasoline but home heating oil, diesel fuel burned by large trucks and machinery, kerosene for aircraft, residual oil for large commercial ships, propane for heating (largely in rural areas that aren’t connected to gas lines) and lubricants. Non-gasoline fuels typically account for a little over half of petroleum usage, with gasoline a bit less than half. (CTC’s carbon-tax model breaks down a lot of these uses.)

On a per-btu basis, i.e., for an equivalent amount of heat or energy, petroleum products are far more costly than methane gas. Gasoline at $4.00 a gallon, the approximate national average pump price in early March, equates to $32 per million Btu; whereas during 2016-2020 methane gas averaged only a little more than $2 per million Btu at the wellhead and $6 delivered to the average customer. (Yes, refining crude oil into petroleum products is really costly.)

We made a back-of-the-envelope estimate of what the disruption of global energy markets due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine is costing U.S. consumers. We assumed a 15 percent rise in petroleum-product prices, along with a 50 percent rise in the wellhead price of methane gas as profit-maximizing owners diverted some supplies to LNG tankers bound for Europe. With these assumptions, the impacts on U.S. consumers — businesses along with households — are in the neighborhood of $400 million a day for higher petroleum fuels and $100 million a day for costlier methane gas. (Gasoline accounts for “only” $150 to $200 million of the $500 million total.)

Mathematically, the total, around $500 million a day, works out to around $4 a day in added costs for an average U.S. household. With a robust carbon tax in place, the supply shock would be far smaller. Households wouldn’t be consuming as much oil, and the increased slack in the world oil business would shrink the opportunities for profiteering by oil owners and traders.

Q3: Is gasoline use sensitive to the price at the pump?

A3: More than most people think, though less than we wish.

We examined the price-elasticity of gasoline in 2015, in a post, What an Energy-Efficiency Hero Gets Wrong about Carbon Taxes. The post presented a linear regression model that correlated year-to-year changes in U.S. gasoline consumption with changes in economic activity (GDP) and in the real (inflation-adjusted) price of gasoline. Here’s what we wrote then:

We “regressed” the annual percentage changes in U.S. gasoline consumption from 1960 through 2014 on three independent variables: (i) the same year’s percentage change in economic activity (GDP); (ii) the same year’s percentage change in the average real retail price of gasoline; and (iii) the average percentage change in that price over the 10 years prior to the current year. The third variable was intended to reflect lags inherent in Americans’ responses to changing gasoline prices, insofar as automobile purchases and location choices that affect usage tend to change over years rather than weeks or months. The parameters may be referred to as income-elasticity, immediate price-elasticity, and lagged price-elasticity, respectively.

Imagine the benefits from impounding vehicles like these for the duration of the Ukraine War — or the climate crisis!

This week we updated the model with gasoline consumption and price data through 2021. Here’s what we found:

- The income-elasticity of gasoline consumption is a little over 0.5 (0.53, to be precise), meaning that a 1 percent rise in GDP is associated with a 0.5 percent rise in gas use.

- The immediate price-elasticity of gasoline consumption is (minus) 0.11, meaning that it takes nearly a 10 percent hike in the average price at the pump to bring about an immediate 1 percent drop in usage; this validates the perception that in the short run. gasoline use is only barely responsive to price changes.

- The lagged price-elasticity of gasoline consumption is (minus) 0.19. The sum of the immediate and lagged price-elasticities is (minus) 0.30, indicating modest sensitivity of usage to price over a longer time horizon. A sustained 10 percent hike in gasoline prices would tend to elicit a 3 percent drop in usage.

(Incidentally, this 3-variable model — actually, we used 5 variables, including “dummy” variables to isolate gas use in 2020 and 2021, the pandemic years — explains nearly 80 percent of the year-to-year variation in U.S. gasoline consumption.)

Here are four takeaways from our modeling:

- Holding prices constant, gasoline usage in the U.S. has been partly decoupled from economic activity, since two units of economic growth lead to only one unit of growth in gasoline use.

- U.S. gasoline demand isn’t entirely price-inelastic, though it is nearly so in the immediate (short) run.

- Over a longer period, demand for gasoline displays some price-sensitivity, suggesting that by raising pump prices, carbon taxes can have some sway over usage.

- Still, the relative price-inelasticity of gasoline indicates that even robust carbon taxes won’t have a big direct effect on usage; the bigger impacts will come from speeding the transition to electric vehicles and, we hope, fostering turns in the culture that promote and valorize reduced fuel use

Q4: How much could the U.S. cut oil demand, right away?

A4: By a lot. (But we won’t.)

In early 2002, not long after the Saudi-enabled attacks that destroyed the World Trade Center, I published a blueprint for achieving an immediate (“overnight”) 5% cut in U.S. oil consumption, with the reductions reaching 10% within six months.

I produced this U.S. oil-saving plan in early 2002, hoping to rally post-9/11 public opinion to slash U.S. oil dependence.

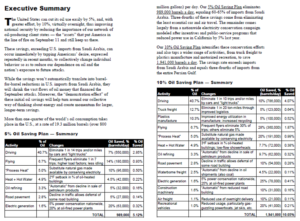

Given the reality that changes in capital stocks that underlie oil consumption — the cars people own, the cities and towns where they live — can’t change overnight, the booklet’s guiding idea was to “collectively change individual behaviors” that added up to the 19.3 million barrels of petroleum products being consumed daily in the U.S.

My thinking then was that behavior changes away from petroleum consumption could finally explode from niche to commonplace if the changes were hitched to a higher purpose — national security and patriotism, in this case. Bicycle commuting, carpooling, thermostat setbacks, electricity conservation would become widespread as their aura changed from fringe-y to patriotic.

Sadly, this never caught on. Our declaration “that we face a choice between love of oil and love of country” and our call to the Bush administration “to break with past policies of subsidizing oil consumption and treating every oil-consuming activity, no matter how discretionary or wasteful, as essential,” fell on deaf ears.

Today, U.S. oil consumption is greater than it was on 9/11. U.S. households, businesses and industry consumed an average of 20,540,000 barrels of petroleum products in 2021, around 5 percent more than the 19,700,000 barrels used daily in 2000.

If anything, calls to alter individual behavior to cut down on consumption of oil and other fossil fuels, whether for geopolitical purposes (to shrink Russian government and oligarch cash reserves) or for climate (to dial back carbon emissions), are frequently derided on the left as “lifestyle-shaming” and diversions from the “urgent task of system decarbonization.” In a New Yorker magazine profile of Sunrise Movement organizers earlier this month, for example, one activist dismissed Al Gore’s exhortation in 2006 to replace electricity-gulping lights because “even if you change all the light bulbs in the country, you don’t come close to preventing catastrophe.” In fact, multitudes of bulb swaps since then have helped flatten U.S. electricity demand, keeping hundreds of millions of tons of coal in the ground — this country’s biggest climate triumph to date.

We conclude this post with a screenshot of the opening pages of “Ending the Oil Age.” The full 44-page report may be downloaded here (pdf). Readers with an historical bent, take note: The report also proposed hefty taxes on gasoline and jet fuel that, in my telling, could replace the patriotic impulse to conserve petroleum as the murderous, petro-dollar-fueled attack on the World Trade Center began to recede into the past.

Pages 1 & 2 from “Ending the Oil Age.” Link to the report is in the last text paragraph, above.

Drew Keeling says

Thanks for this timely heads up.

There is no inherent contradiction between a principled policy on international economic relations, and a common sense domestic energy policy. Reducing dependency on defacto subsidized fossil fuels, locally and globally, serves the common interest of current and future generations.