The campaign to combat climate change by inducing pension funds, universities and other prominent fiduciaries to dump their fossil-fuel holdings has failed. Ten years into the divestment project, it’s time to move on.

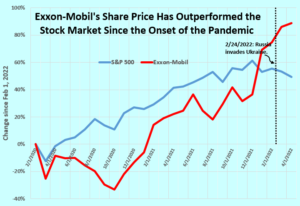

Divestment campaigning doesn’t seem to have damaged Exxon’s share price since 2020.

When the writer and climate activist Bill McKibben kicked off the campaign in a July 2012 Rolling Stone article, Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math, the rationale was three-fold: (1) dry up capital and make it harder for the fossil fuel industry to create new mines, wells, pipelines and terminals; (2) weaken the industry’s social and political standing so it couldn’t easily block pro-climate policy; and (3) by hanging a “Dump Me” sign around Big Oil, amp up climate organizing. Not for nothing did McKibben subtitle his Rolling Stone article, “Make clear who the real enemy is.” It was Exxon and its brethren.

How’s it going, ten years on? Not well. The clearest indication is Exxon-Mobil stock’s new-found attractiveness to investors. From Feb. 1, 2020 to Feb. 1, 2022, a two-year period that predates Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and brackets the Covid-19 pandemic, Exxon’s stock price climbed 75 percent, outpacing the 55 percent rise in the S&P 500 index.

While non-U.S. oil giants Saudi Aramco and BP have appreciated less than the S&P benchmark, the #2 and #3 U.S. oil companies, Marathon Oil and Valero Energy, have matched Exxon’s faster-than-average share price rise. Unsurprisingly, Exxon’s market-beating performance accelerated since Feb. 1, as the oil industry reaps the fruit of high prices without yet suffering much contraction in demand.

It is true that Exxon and other oil majors under-performed the market from 2012 to 2020. So why are oil stocks now so buoyant? The answer lies in robust demand for petroleum products, both in the U.S. (about a fifth of world usage, with half of that in motor fuels) and globally. Until Russia attacked Ukraine, disrupting trade and dampening near-term economic expectations, world petroleum consumption this year was headed to near-record levels.

Is it, though?

More importantly, considering that stock prices essentially embody investors’ expectations of future earnings streams, the lords of capital are betting on the oil and gas business to stay profitable for some time.

Reserves will not stay in the ground, in other words, unless and until consumption shrinks. It ought to be obvious that oil consumption drives production, not the other way around. The same “whack-a-mole” syndrome that made “keep it in the ground” campaigns ineffectual from a climate standpoint (as I lamented in this 2016 post) also afflicts efforts by socially responsible investors to starve capital flows to fossil fuel corporations.

No matter how far divestment penetrates bank boardrooms or Ivy League endowments, a world intent on using fossil fuels can always count on a vast array of wealth holders to finance their resupply.

McKibben admitted as much last fall, shortly after the New York Times reported on meticulous research by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project that found that private equity funds for a decade had been investing $100 billion a year in fossil fuel energy. In an October 2021 Times op-ed (see headline above), he admitted the real purpose of divestment campaigns: to build the climate movement and erode the social and political standing of the fossil fuel industry (what I earlier called aims #2 and #3):

Since most people don’t have oil wells or coal mines in their backyards, divestment is a way to let a lot of people in on the climate fight, because they have a link to a pension fund, mutual fund, endowment or other pot of money. When we began the divestment campaign, our immediate goal was, as we put it, to “take away the social license” of Big Oil. (emphasis added)

This Oct 13, 2021 NY Times story demolished a key rationale for fossil-fuel divestment campaigns.

Movement-building is vital. Eroding the social standing of fossil-fuel extractors and purveyors is overdue. But what happens when divestment activists discover that moving their college or municipal pension fund out of fossil fuels hasn’t visibly changed the material world of energy production and consumption?

In the 2021 op-ed, McKibben added that divestment campaigning “was a vehicle to let people know the essential truth about the fossil fuel industry, which is that its oil, gas and coal reserves held five times as much carbon as scientists said we could safely burn.” That 5-fold incongruity, in fact, was the titular “new math” in his archetypal 2012 Rolling Stone article.

The math is unassailable. McKibben’s new metric demonstrated, ingeniously and incontrovertibly, the incompatibility between oil industry health and planetary health. Yet divestment, as a tactic, hasn’t delivered.

Divestment campaigners have a world of actions and organizing to do instead. For the next six months, though, they need to focus on political action. Electoral action.

Odds be damned, the Democrats have got to hold onto Congress this November. Political commentator Jamelle Bouie reminded us why recently when he was asked why “the Democrats can’t seem to get traction on [climate and other progressive policies] that enjoy broad support”:

In terms of getting policies through Congress, they just don’t have the votes. [But] I think this picture would look very different if there was one more or two more [Democratic] senators. If Cal Cunningham in North Carolina had won [in 2020], if Susan Collins’s opponent in Maine [Susan Gideon] had won, we’d be looking at a very different situation.

Needless to say, a very different situation, of the opposite sort, is what we’ll be looking at if the other, climate-denying, democracy-wrecking party prevails in the midterms. Between now and Tuesday, Nov. 8, not just divestment but probably all climate-focused organizing needs to yield to, or at least be subsumed by, electoral campaigning.

If your state or district is competitive, start electoral organizing now. If not, these resources can plug you in:

- People’s Action has both electoral and non-electoral volunteering.

- Swing Left has local chapters to connect you for phone-calling, post-carding, donating, etc.

- For down-ballot electioneering (which also brings people to vote for up-ballot races): Sister District.

- For Spanish-speaking calling in AZ, connect to Mision por Arizona via Mission for Arizona.

- To donate $$ to grassroots rather than party organizations: Movement Voter Project.

Tom Matte says

Hi Charles, this excellent piece was flagged by a fellow Citizens’ Climate Lobby member. Other data against the divestment delusion: According to the International Energy Agency, in 2021, just 25% of fossil fuel investment and only 1% of coal production investment was in North America; 91% of global investments in coal production and 63% of coal fired power generation was in the Asia-Pacific region. (3) The IEA also notes that fossil fuel investment and production is shifting away from publicly traded companies to nationally-owned companies (not subject to divestment pressures and perhaps benefitting from higher revenues applied to political repression at home and war making abroad) and away from the seven large “Majors” integrated oil and gas companies, The latter now account for just 12% of oil and gas reserves, 15% of production and 10% of estimated emissions from operations. Two reasons for the persistent appeal of divestment. One is that it vilifies brands that have indeed acted badly, but are do not market products that are commodities with brands that are largely irrelevant and that consumers don’t associate with their own status or lifestyle. Another is that the inhabitants of the social and income strata like Bill McKibben, me, and (I assume) you belong to do not pay a large share of our household income for essential energy services. So higher prices for electricity and gas don’t pinch our budgets and we can better afford to evade these with (often subsidized) high-end battery electric vehicles and suburban rooftop solar.

Figure 3

Tom Matte says

Sorry, IEA sources for data and figure (that does not render in comments) are: World Energy Investment 2021 Datafile – Data product [Internet]. IEA. [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/world-energy-investment-2021-datafile

4. The Oil and Gas Industry in Energy Transitions – Analysis [Internet]. IEA. [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-oil-and-gas-industry-in-energy-transitions

Drew Keeling says

Divestment had traction against South Africa’s apartheid (mentioned in McKibben’s 2012 piece) by directing worldwide pressure at a small geographical slice of a small number of multinational corporate operations. Divesting from fossil fuel companies as a tool for climate protection is different, because effective change requires large adjustments across large slices of the global economy.

McKibben’s logic, however, was that while a “more efficient method would be to work through the political system,” one first needed to weaken the “fossil-fuel industry’s political standing,” hence a divestment movement to reduce the power of Big Fossil Fuel on Capitol Hill.

So, now “for the next six months,” regardless of divestment, a renewed “focus on political, electoral action” ?

Yes, indeed. But the time scale challenge grows rapidly more daunting.

Suppose Democrats not only “hold on” to their current share of Congress next November but increase it to 2009’s level (to 58% from today’s 51%). That was the level that could not pass the too weak Waxman Markey cap and trade bill.

We do not have another decade to keep trying and hoping for better luck politically. The IPCC says that to avoid far more disastrous climate change than what is already occurring and coming, global carbon emissions must drop by about half by 2030. After three decades of IPCC warnings, political policies have yet to even stop emissions from increasing.

Better prospects might come from the growing global campaign of lawsuits, against both governments and corporations, described in this week’s Economist (April 23). These recent suits are based on IPCC quantification, actionability from the 2015 Paris Agreement and emerging precedents for the standing of shareholders and future generations, not available fifteen years ago. We now need politicians, voters, lawyers, activists, businesses, technologists, educators, etc. all effectively involved. Carbon budget time is fast running out, and meeting this global challenge requires a bundle of global responses.

James Handley says

Is there a longer-term reason to for responsible organizations and individuals to divest? Fossil fuel corporations are defending climate damage lawsuits. If their shareholders are respected institutions and pension funds, that might weaken the argument for disgorging their ill-gotten gains. But if tehy’re mainly owned by hedge funds and other social predators, judges and juries might decide they deserve to keep nothing.

Also, whatever “movement” existed or exists to advocate taxing climate pollution, it’s hardly done better than the divestment movement in nudging the climate needle. Gimmicky “cap/trade/offset” schemes and silly promises of free money (“carbon dividends”) leave climate policy advocates in the same moral boat as rent-seeking polluters. For climate hawks, the strongest selling point of carbon taxes has always been effectiveness, as your and other economists’ modeling has shown. To members of Congress, revenue gets their attention. Our effort has certainly been buffeted by strong headwinds from the merchants of climate doubt, but framing carbon taxes as free money or hiding the price to pollute inside complex emissions trading schemes look like self-inflicted wounds and at this point, failure to learn from past mistakes.

The “Keep it in the Ground” movement has at least made a dent here and there. https://carbontaxnetwork.org/2018/04/25/carbon-pricing-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/

David Bergman says

Pro divestment: making a statement

Pro divestment: investments funds diverted to investing in companies producing or developing renewable energy.

Against divestment: losing the ability to influence the company via shareholder actions. BUT that ability is useful only if you try to (and can) be heard. Small investors have little voice, and many corporate boards make it difficult or impossible to take action contrary to their wishes.

Lorna Salzman says

I flagged McKibben as a climate charlatan over ten years ago. His failure to promote effective energy policies, his failure to conduct citizen campaigns with specific instructions for what the public and his refusal to support a carbon tax even as he said we should ‘put a price on carbon” means that we lost a lot of time twiddling our thumbs because McKibben had no political smarts and no leadership qualities.

The media and lawmakers loved him precisely because he didnt rock and boat or encourage “radical”

policies or legislation. He was their star. Meanwhile the rest of us just sat back as he advised industry to

“go green” to give themselves a green image…nothing that changed their profits or way of doing business. McKibben is responsible for wasting well over a decade on a useless divestment campaign that he even now says was deceptive. I placed an ad in The Nation in 2010 asking him why he had no

public positions on energy policy whatsoever.. He never responded.. It is truly depressing to know how many people were fooled by him. And still are.