(This post was amended on March 31 to include rebuttals of our criticism of the Montana climate-change lawsuit from two distinguished participants.)

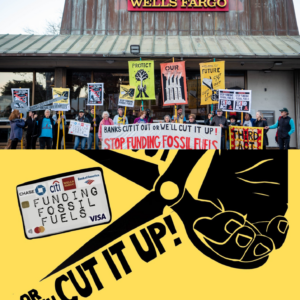

Climate agitation was much in the news last week. The Guardian reported on a forthcoming Harvard Environmental Law Review paper suggesting that fossil fuel companies could be held liable for homicide from deaths caused by climate change. A New York Times front-page story previewed a courtroom trial to determine if Montana policies promoting fossil fuels violate that state’s constitutional protections of a healthful environment. And in dozens of cities, activists assembled by noted climate author-organizer Bill McKibben tore up their Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo and Bank of America credit cards to spotlight the big banks’ financing of $1 trillion in fossil fuel projects over the past five years.

In other climate news, however, suburban legislators are contesting a bold initiative from New York Gov. Kathy Hochul to compel New York City and surrounding counties to expand housing supply. New York City’s public transit provider is scrounging for revenues to shore up declining subway and bus farebox receipts stemming from the triple-whammy of residual Covid worries, violent-crime fears, and working-from-home. Around the country, meanwhile, just about all of the gargantuan road-widening projects listed in U.S. PIRG’s most recent Highway Boondoggles report are proceeding apace.

“States’ rights” have become “local control.” L: Wallace for President rally, 1972, courtesy Google Images. R: Ryan Lowry for the NY Times, accompanying March 22, 2023 opinion essay, “NIMBYs Threaten a Plan to Build More Suburban Housing,” by Times editorial writer Mara Gay. Photo was captioned, “Legislators protested Gov. Kathy Hochul’s housing plan in Albany on Monday.” Faces and demographics in the two photos, taken more than half-a-century apart, are hard to distinguish.

Yes, we’re juxtaposing.

The three just-noted happenings threaten to lock in place profligate fossil fuel consumption and associated carbon emissions. Highway widenings engender more driving (“induced demand,” it’s called). Fare hikes and service cuts to transit in NYC and elsewhere will do the same. And bottling up housing supply, as New York’s suburbs and my own borough of Manhattan, along with affluent cities and towns all over the U.S. have been doing for decades, guarantees urban stasis and its evil twin of exurban sprawl, with its accoutrements of carbon-spewing SUV’s, manses and subdivisions — not to mention segregation.

Litigating for Climate

These carbon accelerants might be more bearable if the climate agitation mentioned at the top had genuine prospects for cutting emissions. Do they? Not likely.

Indicting, much less convicting, officers of fossil fuel companies for killing people via their emissions-induced climate change is the definition of quixotic — to my untutored eye, anyway. In court, Big Oil will simply point to the tens of billions of lives uplifted by the fruits of their fuels. And they won’t be spouting nonsense. The raising up of most of humankind out of subsistence, and the resulting cradle-to-grave lengthening of human lifespans, could not have happened without the carbon-fueled Industrial Revolution. Set against those numbers, the millions — if that — of lives provably lost because of climate change will appear as a mere rounding error.

To be sure, the still-rising use of fossil fuels globally has now burst past the point of positive net benefits, especially with the advent, at last, of scalable non-carbon ways to power civilization. But actually effectuating the transition seems a matter for politics, with or without judicial support.

And even if some clarion guilty verdict were rendered in some court, what would be the remedy? Would the fossil fuel industry be made to dismantle itself? What about the billions of motorists, manufacturers and other consumers and producers who would clamor for more. Sorry, there’s no bypassing the messy work of using pricing, regulation and innovation to get off fossil fuels.

I’m almost as skeptical re the Montana litigation — notwithstanding the earnestness of the young plaintiffs, including two brothers who not only are the sons of firearms-industry apostate Ryan Busse but who were motivated to join the lawsuit by the climatological deterioration of their beautiful corner of northwest Montana.

I identify with Lander and Badge Busse. Melting snow in nearby Glacier National Park helped trigger my ecological awakening, but in an opposite fashion from theirs. On a long-ago day in July, driving on the park’s Going-to-the-Sun Road with my grade-school pal, I parked our tiny Renault auto to fetch water dripping from roadside snowbanks. We filled our canteens and started walked uphill toward the source. An hour later, we were a thousand vertical feet above the roadway and following real-life mountain goats under an impossibly blue sky. Bookending our hike into the Grand Canyon a week earlier, that day became my gateway into love of wildness, defense of clean air, and a career in environmental policy analysis and activism.

Most of Glacier’s glaciers are now diminished if not gone, making the lawsuit, Held v. State of Montana, painful as well as valiant. Yet even if the brothers and their co-litigants win their case, what exactly is the remedy? The Montana Supreme Court possesses no magic button whose pressing can end the burning of fossil fuels. Stop drilling or mining in Montana, and producers will up their output from Wyoming. Stop it in all 50 states, and the same suppliers will boost production overseas. Sure, impeding fuel extraction will incrementally drive up fuel prices and take a bite out of demand, but that’s just a sideways blow at best. The solution, as CTC has argued since our founding in 2007, lies in throttling demand for carbon, not stoppering supply.

Montana litigation supporters weigh in

Shortly after this post went up, CTC received this brief rebuttal from a long-time supporter of the Montana suit and the larger Our Children’s Trust campaign to enshrine a legal right to a safe climate:

The Montana climate suit seeks to build case law affirming a right to a stable, livable climate. I liken it to the long-term legal struggle to secure equal treatment under the law for women and people of color. For example, the legal battle to desegregate schools was a long one built on case law. I agree that any individual state has limited ability to impose a price on emissions, but the Juliana vs. U.S. suit does. It seeks a science-based reduction in emissions sufficient to maintain a stable, livable climate, and proposes a carbon tax as the single most effective policy to achieve that goal. Likely the courts will only impose emission reductions. Politicians will then be tasked with submitting a plan that is affordable and effective. The Montana and other suits build case law affirming the damage caused by fossil fuel emissions and a right to a livable climate. Courts act more on evidence and less on short-term political pressure.

We also received this note from noted environmental attorney and climate-law expert Michael Gerrard, who directs the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School and was featured in the New York Times story noted at the top of this post:

I think we need to attack both the demand side and the supply side. No one action will affect the supply on a macro scale, but cumulatively many could. Montana is one of the nation’s largest fossil fuel suppliers, and if the courts shut down some of that, it would be a good thing. The judge, at least, is taking the case seriously. Whether or not the Montana Supreme Court upholds a decision for the plaintiffs, the case will cast a harsh light on the fossil fuel companies. Most of these campaigns are largely aimed at delegitimizing the fossil fuel companies and reducing their political clout. That is having some effect in blue states, where quite a few strong climate laws are being enacted over the opposition of the fossil companies. And keep in mind that each new coal mine, each new gas-fueled power plant, and so forth, creates a constituency for its long-term preservation; that needs to be resisted.

CTC collage from two separate photographs on Third Act website, snipped on March 30, 2023.

Banks and Climate

We come now to last week’s bank protest that Bill McKibben organized with his new “Community of Americans,” Third Act.

As much as I admire Bill’s unflagging zeal and his Third Act cohorts’ earnest willingness to put themselves out there, I strongly question targeting banks as a cause of fossil fuel exploitation and a locus for climate activism.

How will bank reformation impact the use of cars, trucks and planes in the U.S. or elsewhere — use that requires purchases of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel that in turn provide both the financial wherewithal and the political muscle to drill, extract, refine and transport petroleum products whose combustion releases the carbon dioxide that is wrecking our climate?

Should not Third Act and indeed the entire climate movement be organizing and demonstrating for demand-cutting policies and developments such as mixed-use and dense housing, functional-or-better public transportation, bikeable and walkable streets, fuel-economy standards without “light truck” loopholes, and the like? Wouldn’t their energies accomplish more, both short- and long-term, if they were to swarm Albany and other state capitals to demand upzoning, no more highway widenings, and permitting reform to circumvent anachronistic regulations hindering wind farms and solar homes?

In response, Bill would probably say “We need to remind people of the connection between cash and carbon. Literally, somebody who has $125,000 in those banks [Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo, Bank of America] is producing more [carbon] because it’s being lent out to pipelines and frack wells than all the cooking, flying, heating, driving, cooling that the average American does in a year. Five thousand dollars in [those banks] produces more carbon than flying back and forth across the country.”

How do I know? Because that’s exactly what he said on Democracy Now on the morning of the protests (quoted segment begins around 37:45). Try as I might, I can’t follow the logic.

Coda

Notice I haven’t mentioned carbon pricing, except tangentially. Here at CTC we’re laying low on carbon taxing for the time being. U.S. politics still aren’t ready, what with climate-averse Republicans occupying half of Congress, and Democrats wary of the difficult politics. We focus on what’s possible in the here-and-now.

Last year it was the praiseworthy (if imperfect) Biden-Schumer Inflation Reduction Act. This year we’re continuing to do what we can to bring congestion pricing for New York City into being. We’re also quietly nurturing a promising new avenue to advance a New York State carbon price. Please stay tuned!

Drew Keeling says

Thanks for this timely analysis, although I would suggest that “sound and fury signifying” a big question mark also applies -and has been timely- to most of the agitation about climate change and energy policy over the past couple of decades (CTC being a welcome exception).

The Montana lawsuit caught my attention recently in part due to my own visits there, going back to a Glacier Park trip in 1979, hitching a ride late in the day in one of the vintage park buses on the Going-to-the-Sun road.

A couple of particularities about this suit seem notable:

1. Although I am not a lawyer, the case appears to be rooted in some unusually strong provisions of the Montana state constitution, including the preamble, which begins with:

“We the people of Montana grateful to God for the quiet beauty of our state, the grandeur of our mountains, the vastness of our rolling plains, and desiring to improve the quality of life…”

Plus, the “Declaration of Rights” which starts off with:

“the right to a clean and healthful environment”

And, perhaps most saliently, the “Environment and Natural Resources” article opening with:

“The state and each person shall maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and FUTURE generations.” [emphasis added).

Depending on various legalities no doubt, one conceivable outcome could be damage payments in compensation for the plaintiffs’ Constitutional rights having been violated (which might include for example losses to ranches and livelihoods attributable to extreme weather (partly) attributable to carbon emissions). If that sort of judgment were later scaled up to cover many thousands of people across Montana, it might be in the perceived financial interest of the state’s taxpayers to have the legislature take up the “messy work” of reducing reliance on fossil fuels, instead of making large ongoing damages payments. One might then further imagine the actions of young people in Montana impacting attitudes in Wyoming and Idaho, etc.

2. The logic of CTC (presented in the “Coda”) seems to also apply to the generation of Montanans suing their state authorities, e.g. “laying low” on legislative reform “for the time being” because “politics still aren’t ready.” And thus focusing -for now- on the courts instead.