The impossibility of throttling Big Oil through fossil fuel divestment campaigns was laid bare last week when ExxonMobil announced it was acquiring Pioneer Natural Resources, the #1 driller in the #1 producing U.S. oilfield, the Permian Basin.

Chart from macrotrends.net shows ExxonMobil’s market capitalization (stock price x shares outstanding) last week near an all-time high.

In a transaction priced at $59.5 billion, Pioneer shareholders will receive slightly more than 2.3 shares of ExxonMobil stock for each Pioneer share. No banks are involved, no debt, no third parties; and, most noteworthy, no cash. Pioneer’s management evidently holds Exxon’s current and future financial strength in such high regard that it was willing to sign on to an all-stock deal.

Had it been necessary, though, Exxon could have bankrolled the entire acquisition using cash generated by its sales of petroleum products to U.S. and world motorists, truckers, air travelers and shippers. Last year alone, Exxon generated more than enough cash flow, $76.8 billion, to buy Pioneer outright. Its market capitalization stands at $450 billion, triple the lows during the 2020 pandemic year and higher than the $400 billion in 2012, when climate author-activist Bill McKibben kicked off the divestment movement with his Rolling Stone manifesto, Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.

Photos by Johnny Silvercloud (L, 2015) and Herb Keeney (R, 2016). Thousands of similar images and hundreds of divestments haven’t crimped the coffers of Exxon and its oil brethren.

McKibben was admirably candid about wanting to “make clear who the real [climate] enemy is”: the fossil-fuel industry, led and epitomized by the oil-and-gas giant ExxonMobil. The eleven intervening years have cemented Exxon’s standing as Big Oil incarnate. Not only is Exxon the industry’s most technologically proficient and politically connected member, it’s the one that for decades sowed disinformation about climate change even as its own scientists advised management to fortify the company’s drilling platforms against rising seas.

Unsurprisingly, “Exxon Knew” ranks high among contemporary climate-protest slogans. And the company certainly merits every ounce of opprobrium directed at it. Divestment was a righteous idea, but it has proven futile.

Wake-Up Call

The Pioneer acquisition should be a wake-up call. If the wave of divestments over the past decade by universities, philanthropies and pension funds had genuinely dented oil industry prospects, Exxon’s stock wouldn’t have had the cachet to lure Pioneer into an all-stock purchase. Nor would Exxon have been able to pull off a Plan B of forking over $60 billion in cash. The ease of the acquisition puts the lie to divestment’s starve-and-shame paradigm intended to dry up dollars and discredit industry brands.

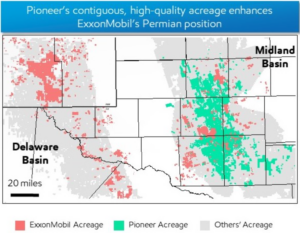

Permian Basin map from ExxonMobil Oct 11 news release.

Pressuring institutions to divest from fossil fuels never made much sense as a pro-climate strategy. Targeting any one oil company was never going to be able to restrain carbon emissions. No single company supplies more than a small slice of the world’s petroleum.

Indeed, as Bloomberg News reported last week, even with Pioneer, Exxon will account for only 15 percent of Permian Basin extraction and a far smaller share of world oil production — three or four percent, according to my calculations. At that modest scale, a hole in any one company’s finances would simply make room for others.

Divestment’s futility actually went deeper, though. In the oil business, access to capital markets matters hardly at all. Most of the time the industry is flush with cash. Just about everything it does — exploration, extraction, pipelining, refining, selling — is self-financing, paid for by the ceaseless ka-ching from sales of gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, bunker fuel and other petroleum products, not to mention natural (methane) gas, which in 2022 provided nearly three-fourths as much primary energy worldwide as petrol, according to BP’s 2023 Statistical Review of World Energy (covering 2022).

To be fair, divestment campaigning did appear to penetrate Exxon’s inner sanctum in 2021, when the activist hedge fund Engine No. 1 succeeded in electing three directors to ExxonMobil’s 13-person board. “Exxon’s Board Defeat Signals the Rise of Social-Good Activists,” trumpeted the New York Times headline reporting the surprise incursion. Yet the ideological impact, if there was one, was short-lived. All three insurgent members backed the Pioneer acquisition, the Wall Street Journal reported last week.

WSJ Oct 14 headline canonizing Exxon CEO Woods for his $60B Permian Basin play.

Indeed, in the Journal story, Charles Penner, architect of the Engine No. 1 campaign, says the Pioneer deal “shows Exxon had heard some of the campaign’s critiques and changed its approach to focus on returns instead of costly megaprojects more dependent on long-term demand.” Oof. The story has nothing from Engine No. 1 on Exxon’s present or future complicity in climate-damaging emissions generated from its products. And nothing in its detailed portrait of CEO Darren Woods suggests that worries about divestment ever cost him a moment’s sleep.

What To Do?

There are so many climate campaigns needing and deserving of the energies now squandered pursuing fossil-fuel divestment. I suggested a few of them in The Climate Movement In Its Own Way, my April 2022 article in The Nation (reposted here at CTC). Here’s a top-10 list (in no particular order):

- Policy campaigns to curb motor vehicle size and weight

- Organizing to expedite up-zoning in cities and suburbs and otherwise promote housing density

- Advancing walkable, bikeable and transit-oriented communities

- Restricting and overcoming NIMBY power to block wind farms and solar arrays

- Supporting the operability of existing, well-functioning nuclear power plants

- Advancing congestion pricing and other road-pricing / traffic-pricing proposals (valuable for themselves and as templates for broad carbon-emission pricing)

- Taxing extreme wealth, to both attack luxury emissions and promote social solidarity needed to tackle carbon consumption

- Shrinking the local, state and national reach of the world’s sole major climate-denying political party (whose dysfunction is currently in especially plain sight, as NY Times columnist Jamelle Bouie trenchantly documented this week)

- Reducing animal agriculture through both culture and policy change

- Advancing or at least keeping alive the idea of robust carbon pricing at the state and especially national level

Note that all of the above measures, except perhaps #8, attack carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions from the demand side, insulating them from the all-too-real whack-a-mole syndrome that undermines most supply-side climate campaigns due to global substitutability by which increased drilling “there” offsets halts to drilling “here.”

Missing from the list: abetting the electrification of cars, trucks, cooking, heating and industry. Why not? For one thing, “electrify everything” has no shortage of NGO advocates like Rewiring America, and, thanks to President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, it enjoys generous federal subsidies. For another, decarbonization of U.S. grids is far from complete and, in many states and regions, painfully slow.

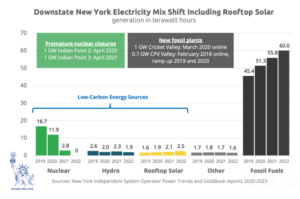

Graphic and data curated by Isuru Seneviratne, Nuclear NY, Oct 2023.

Here in New York City, CTC’s home territory, fossil fuel burning today generates more than 90 percent of all electricity (see graphic from Nuclear NY), down from 70 percent since the 2020-2021 closure of the downstate grid’s only large-scale non-carbon generator, the Indian Point nuclear plant.

As a result, rarely if ever is the incremental electricity that my grid calls on to recharge EV’s or energize electric heat pumps generated from a non-carbon source. The same is true at present in much of the United States. Electrification, an essential long-term program, is not yet a carbon-eliminating panacea .

Want to hurt Exxon AND fight climate change? Work to bring robust carbon pricing back into the national policy conversation. A meaningful carbon price — one that quickly ramps up to triple digits per ton of CO2 — will crimp the oil business, the coal business and the fossil-gas business, harming the fossil fuel industry’s shareholder value and political power, while effectuating steady and significant reductions in combustion. And, when considering the to-do list above, keep in mind that robust carbon pricing (#10) enhances all of the others.

Addendum: Two days after posting, we learned that Chevron is acquiring oil giant Hess Corp. in another all-stock deal, this one valued at $53 billion.

Lorna Salzman says

I am still waiting for someone to do a comprehensive study of how much renewable energy sources could be built (and in how much time) for the roughly $15 billion cost of a new nuclear power plant. Every dollar invested in nuclear means one less for renewables, as well as postponing real solutions for a decade or more to bring a reactor in line…..at a higher cost as well.

Charles Komanoff says

There are a zillion such studies. The relevance of them to this post is what, exactly?

Drew Keeling says

Yes, a carbon tax (preferably fully revenue neutral, progressively applied, and backed by border fees) remains the most efficient and effective approach available. Except that, having massively blown the opportunity to do that over multiple decades, time has mostly run out, ergo some of the other 9 steps will also be needed if a non-disastrous climate is to have a reasonable chance of surviving.

Or, if one were to invoke Bill McKibben’s world war metaphor, one might think of another measurenot on the list: nationalization.

The drawback of that, however: Where is the political competence to pull it off ?

From a purely managerial perspective, the reverse might work better. Turn the government over to Exxon.

Except that something sort of like that was tried already (during the prior US federal administration) and did not go very well, either.

Kipchoge Spencer says

Real question: If access to capital isn’t a challenge for the industry, are you also saying that the $4.6 trillion the world’s 60 largest commercial and investment banks invested in fossil fuels between 2015-2022 was just incidental?

Charles Komanoff says

Hi Kipchoge (and apologizing for taking several weeks to reply) —

Basically, yes. I believe the $4.6T invested over those years *was* largely incidental.

Consider this quick calculation: Over that 8-year period, world petroleum consumption averaged around 90 million barrels/day, I think. Assuming the average non-taxed petroleum product was $3 per gallon, and factoring in 42 gallons per barrel and 365 days per year, along with 8 years, the revenue generated was around $33 trillion. (I calculated 90 x 10^6 bbl/day x 365 days/year x 42 gal/bbl x 8 years.) Now, while I’m not expert in oil-industry finance, I would guess that 20% of those revenues accrued as profit, which works out to $6.6 trillion. I would double that to capture methane-gas and coal, taking the apparent profit to $13 trillion, which is nearly triple the $4.6T you cited.

This doesn’t completely moot the $4.6T, of course, but it puts it in perspective. What are your thoughts?

Kipchoge Spencer says

Thanks for the reply, Charles. Here’s mine with my own delay! While I buy that divestment hasn’t solved it, I don’t think I agree with the math/economics of your position here. (I’m not an industry economist either, so this reflects a simplistic understanding.) In the article, you say that Exxon’s cash flow was $77B last year and that they could have just bought Pioneer outright. I think this is basically right, if not exactly as you put it. The important number is not cash flow, but free cash flow, which was $62B, still enough to buy Pioneer for cash. But, doing so would have put Exxon’s free cash flow at $2B for 2022, which would really, really disappoint Wall Street. Industry wide in 2022, free cash flow hit a record $1.4T, while bank financing of the industry was $669B. That financing allowed the industry to report record profits and payout record dividends. Without the financing, all the numbers would look roughly half as good. At the sniff test level, if the industry could invest all its cash and still report equally high profits, it would; it just doesn’t compute that the industry could do nearly as much harm without the extra cash that banks and investors supply.

While I agree that the supply side is a hard side, and love your suggestions, I’m not convinced that the demand side is simpler. When someone says, “ that hasn’t solved it,” I usually say, yeah, neither has anything else. I think we should keep working on all of the above, each of us to our own impulses. In the absence of it having been solved, with a million dimensions of problems and solutions, it feels challenging to try to empirically evaluate all the world’s climate advocacy and figure out what’s most effective. I talked to a donor the other day who maintained that supporting Sunrise was the “worst investment we ever made.” I believe Sunrise was absolutely foundationally critical to the IRA. Your mileage may vary. A tipping point where fossil fuels are suddenly not tolerated in polite company would greatly abet all efforts, and that tipping point is helped along by making a pariah of the industry in as many venues as possible, including finance. Did you catch The Carbon Bankroll report, showing how big brands’ cash is financing fossil fuels? This seems like one such potential leverage point for pariahification. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6281708e8ff18c23842b1d0b/t/6283204b3556a5125ce13b37/1652760661661/The+Carbon+Bankroll+Report+%285-17-2022%29.pdf

Would you advocate for all the orgs doing supply side pressure to reorient completely?

Charles Komanoff says

Dear Kipchoge —

Thanks for your interesting and thought-provoking note,

But I think my point stands that Big Oil has little need for bank financing.

Remember, Exxon paid for Pioneer entirely with Exxon stock, $59 billion worth. No up-front bank money was involved.

What enabled the deal, then? It was Pioneer management’s faith in Exxon’s future earnings streams, which resides in the gazillion petrol-burning sport utes on America’s and other countries’ roads.

*That*, not bankers’ boardrooms, is Exxon’s superpower.

To your other points:

While I love the idea of shaming the fossil fuels industry into pariah status, I can’t envision that happening except perhaps at the tail end of the transition from FF’s, at which point it won’t matter much.

And yes, CTC wants and advocates for supply side activists to switch to demand side — by targeting “luxury carbon,” by campaigning to rein in car and highway bloat, by emphasizing systemic changes like upzoning cities and suburbs to accommodate climate-friendly density, and above all through carbon pricing. This idea permeates most of our posts and pages.

Best,

Charles

Kipchoge Spencer says

Dear Charles, I agree with you about what enabled that deal. I think you are also implying that Exxon can do every deal it wants without the help of banks as long as the demand for its product exists. I think that’s too hand wavy. As you know, there’s no fixed demand for oil. There’s demand elasticity, there’s a finite amount of its stock it can trade for deals, and there’s a finite amount of free cash it can use to finance new exploration. Wind and sun are displacing coal right now in part because wind and sun are cheaper. The cost of capital is one factor in the cost of energy development and energy itself. When fewer lenders are willing to lend, the cost of capital goes up. If the industry didn’t have access to $669B in loans in 2022, it would have done less exploration and expansion. I don’t think it could have substituted its own cash for that exploration without Wall St, price and demand consequences, and because the absolute and relative amount of financing was so extensive, it’s difficult to believe that we’re not talking about real carbon.

If the CTC wants to make oil more expensive by taxing it in order to reduce demand, doesn’t it make sense to also make it more expensive by eliminating one of the de facto subsidies it enjoys vis a vis access to cheap capital?

Warmly,

Kipchoge