Next month will mark four years since the Indian Point nuclear power plant north of New York City began to be shut down.

Indian Point 2 was closed on April 30, 2020. Indian Point 3’s closure followed a year later. The two units, rated at roughly 1,000 megawatts each, started operating in the mid-1970s. A half-century later, their reactor cores lie dismembered. Both units are irretrievably gone, for better or worse.

I believe the closures are for the worse — and not by a little. The loss of Indian Point’s 2,000 MW of virtually carbon-free power has set back New York’s decarbonization efforts by at least a decade. And that’s almost certainly an understatement.

I hinted at this in Drones With Hacksaws: Climate Consequences of Shutting Indian Point Can’t Be Brushed Aside, a May 2020 post in the NY-area outlet Gotham Gazette. Over time I grew more outspoken. In two posts for The Nation in April 2022 (here and here) I invoked Indian Point to urge Californians to revoke a parallel plan to close Pacific Gas & Electric’s two-unit Diablo Canyon nuclear plant, which I followed up with a plea to Gov. Gavin Newsom to scuttle the shutdown deal, co-signed by clean-air advocate Armond Cohen and whole-earth avatar Stewart Brand. Which the governor did, last year.

Once I had regarded nuclear plant closures as no big deal. Now I was telling all who would listen that junking high-performing thousand-megawatt reactors on either coast was a monstrous climate crime, the carbon equivalent to decapitating many hundreds of giant wind turbines — a metaphor I employed in my Gotham Gazette post. My turnaround rested on two clear but overlooked points.

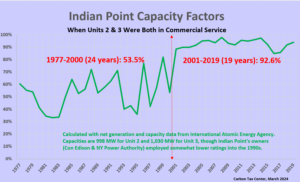

One was that nearly all extant U.S. nukes had long ago morphed from chronic inconsistency into rock-solid generators of massive volumes of carbon-free kilowatt-hours, with “capacity factors” reliably hitting 90% or even higher. This positive change should have put to rest the antinuclear movement’s shopworn “aging and unsafe” narrative about our 90-odd operating reactors. It also elevated the plants’ economic and climate value, making politically forced closures far more costly than most of us had imagined.

The other new point is connected to carbon and climate: The effort to have “renewables” (wind, solar and occasionally hydro) fill the hole left from closing Indian Point or other nuclear plants isn’t just tendentious and difficult. Rather, the very construct that one set of zero-carbon generators (renewables) can “replace” another (nuclear) with no climate cost is simplistic if not downright false, as I explain further below.

These new ideas came to mind as I read a major story this week on the consequences of Indian Point’s closure in The Guardian by Oliver Milman, the paper’s longtime chief environment correspondent. To his credit, Milman delved pretty deeply into the impacts of reactor closures — more so than any prominent journalist has done to date. Nonetheless, it’s time for coverage of nuclear closures to go further. To assist, I’ve posted Milman’s story verbatim, with my responses alongside.

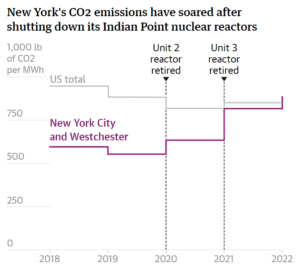

A nuclear plant’s closure was hailed as a green win. Then emissions went up.By Oliver Milman, The Guardian, March 20, 2024 When New York’s deteriorating and unloved Indian Point nuclear plant finally shuttered in 2021, its demise was met with delight from environmentalists who had long demanded it be scrapped. But there has been a sting in the tail – since the closure, New York’s greenhouse gas emissions have gone up. Castigated for its impact upon the surrounding environment and feared for its potential to unleash disaster close to the heart of New York City, Indian Point nevertheless supplied a large chunk of the state’s carbon-free electricity.  Guardian graphic using eGRID data for NYCW subregion. The chart’s other half was excised to fit the available space. Since the plant’s closure, it has been gas, rather then clean energy such as solar and wind, that has filled the void, leaving New York City in the embarrassing situation of seeing its planet-heating emissions jump in recent years to the point its power grid is now dirtier than Texas’s, as well as the US average. “From a climate change point of view it’s been a real step backwards and made it harder for New York City to decarbonize its electricity supply than it could’ve been,” said Ben Furnas, a climate and energy policy expert at Cornell University. “This has been a cautionary tale that has left New York in a really challenging spot.” The closure of Indian Point raises sticky questions for the green movement and states such as New York that are looking to slash carbon pollution. Should long-held concerns about nuclear be shelved due to the overriding challenge of the climate crisis? If so, what should be done about the US’s fleet of ageing nuclear plants? For those who spent decades fighting Indian Point, the power plant had few redeeming qualities even in an era of escalating global heating. Perched on the banks of the Hudson River about 25 miles north of Manhattan, the hulking facility started operation in the 1960s and its three reactors at one point contributed about a quarter of New York City’s power. (Guardian/Milman continued) It faced a constant barrage of criticism over safety concerns, however, particularly around the leaking of radioactive material into groundwater and for harm caused to fish when the river’s water was used for cooling. Pressure from Andrew Cuomo, New York’s then governor, and Bernie Sanders – the senator called Indian Point a “catastrophe waiting to happen” – led to a phased closure announced in 2017, with the two remaining reactors shutting in 2020 and 2021. The closure was cause for jubilation in green circles, with Mark Ruffalo, the actor and environmentalist, calling the plant’s end “a BIG deal”. He added in a video: “Let’s get beyond Indian Point.” New York has two other nuclear stations, which have also faced opposition, that have licenses set to expire this decade. But rather than immediately usher in a new dawn of clean energy, Indian Point’s departure spurred a jump in planet-heating emissions. New York upped its consumption of readily available gas to make up its shortfall in 2020 and again in 2021, as nuclear dropped to just a fifth of the state’s electricity generation, down from about a third before Indian Point’s closure. This reversal will not itself wreck New York’s goal of making its grid emissions-free by 2040. Two major projects bringing Canadian hydropower and upstate solar and wind electricity will come online by 2027, while the state is pushing ahead with new offshore wind projects – New York’s first offshore turbines started whirring last week. Kathy Hochul, New York’s governor, has vowed the state will “build a cleaner, greener future for all New Yorkers.” Even as renewable energy blossoms at a gathering pace in the US, though, it is gas that remains the most common fallback for utilities once they take nuclear offline, according to Furnas. This mirrors a situation faced by Germany after it looked to move away from nuclear in the wake of the Fukushima disaster in 2011, only to fall back on coal, the dirtiest of all fossil fuels, as a temporary replacement. “As renewables are being built we still need energy for when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining and most often it’s gas that is doing that,” said Furnas. “It’s a harrowing dynamic. Taking away a big slice of clean energy coming from nuclear can be a self-inflicted wound from a climate change point of view.” With the world barreling towards disastrous climate change impacts due to the dawdling pace of emissions cuts, some environmentalists have set aside reservations and accepted nuclear as an expedient power source. The US currently derives about a fifth of its electricity from nuclear power. Bill McKibben, author, activist and founder of 350.org, said that the position “of the people I know and trust” is that “if you have an existing nuke, keep it open if you can. I think most people are agnostic on new nuclear, hoping that the next generation of reactors might pan out but fearing that they’ll be too expensive. “The hard part for nuclear, aside from all the traditional and still applicable safety caveats, is that sun and wind and batteries just keep getting cheaper and cheaper, which means the nuclear industry increasingly depends on political gamesmanship to get public funding,” McKibben added. (Guardian/Milman continued) Wariness over nuclear has long been a central tenet of the environmental movement, though, and opponents point to concerns over nuclear waste, localized pollution and the chance, albeit unlikely, of a major disaster. In California, a coalition of green groups recently filed a lawsuit to try to force the closure of the Diablo Canyon facility, which provides about 8% of the state’s electricity.

Templeton said the groups were alarmed over Diablo Canyon’s discharge of waste water into the environment and the possibility an earthquake could trigger a disastrous leak of nuclear waste. A previous Friends of the Earth deal with the plant’s operator, PG&E, to shutter Diablo Canyon was clouded by state legislation allowing the facility to remain open for another five years, and potentially longer, which Templeton said was a “twist of the knife” to opponents. “We are not stuck in the past – we are embracing renewable energy technology like solar and wind,” she said. “There was ample notice for everyone to get their houses in order and switch over to solar and wind and they didn’t do anything. The main beneficiary of all this is the corporation making money out of this plant remaining active for longer.” Meanwhile, supporters of nuclear – some online fans have been called “nuclear bros” – claim the energy source has moved past the specter of Chernobyl and into a new era of small modular nuclear reactors. Amazon recently purchased a nuclear-powered data center, while Bill Gates has also plowed investment into the technology. Rising electricity bills, as well as the climate crisis, are causing people to reassess nuclear, advocates say. “Things have changed drastically – five years ago I would get a very hostile response when talking about nuclear, now people are just so much more open about it,” said Grace Stanke, a nuclear fuels engineer and former Miss America who regularly gives talks on the benefits of nuclear. “I find that young people really want to have a discussion about nuclear because of climate change, but people of all ages want reliable, accessible energy,” she said. “Nuclear can provide that.” |

The forces that won Indian Point’s closure were blind to the climate cost.By Charles Komanoff, Carbon Tax Center, March 23, 2024 New Reality #1: Indian Point wasn’t “deteriorating” when it was closed.“Deteriorating and unloved” is how Milman characterized Indian Point in his lede. “Unloved?” Sure, though probably no U.S. generating station has been fondly embraced since Woody Guthrie rhapsodized about the Grand Coulee Dam in the 1940s. But “deteriorating”? How could a power plant on the verge of collapse run for two decades at greater than 90% of its maximum capacity?  Calculations by author from International Atomic Energy Agency data. Diablo Canyon has also averaged over 90% CF since 2000. Had Indian Point been less productive, the jump in the metropolitan area’s carbon emission rate would have been far less than the apparent 60 percent increase in the Guardian graph at left. Though the “electrify everything” community is loath to discuss it, the emissions surge from closing Indian Point significantly diminishes the purported climate benefit from shifting vehicles, heating, cooking and industry from combustion to electricity . The impetus for shutting Indian Point largely came through, not from then-Gov. Cuomo.Milman pins the decision to close Indian Point on NY Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Vermont’s U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. While Cuomo backed and brokered the deal (which Sanders had nothing to do with), the real push came from a coalition of NY-area environmental activists led by Riverkeeper, who, as he notes, “spent decades fighting Indian Point.” And it was relentless. The wellsprings of their fight were many, from Cold War fears of anything nuclear to a fierce devotion to the Hudson River ecosystem, which Indian Point threatened not through occasional minor radioactive leaks but via larval striped bass entrainment on the plant’s intake screens. Their fight was of course supercharged by the 1979 Three Mile Island reactor meltdown in Pennsylvania and, later, by the 9/11 hijackers’ Hudson River flight path. But as I pointed out in Gotham Gazette, few shutdown proponents had carbon reduction in their organizational DNA. None had ever built anything, leaving many with a fantasyland conception of the work required to substitute green capacity for Indian Point. (CTC/Komanoff continued) And while the shutdown forces proclaimed their love for wind and solar, their understanding of electric grids and nukes was stuck in the past. To them, Indian Point was Three Mile Island (or Chernobyl) on the Hudson — never mind that by the mid-2010s U.S. nuclear power plants had multiplied their pre-TMI operating experience twenty-fold with nary a mishap. No, in most anti-nukers’ minds, Indian Point would forever be a bumbling menace incapable of rising above its previous-century average 50% capacity factor (see graph above). Most either ignored the plant’s born-again 90% online mark or viewed it as proof of lax oversight by a co-opted Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Note too that the “hulking facility,” as Milman termed Indian Point, lay a very considerable 35 air miles from Columbus Circle, rather than “25 miles north of Manhattan,” a figure that references the borough’s uninhabited northern tip. NYC residents had more immediate concerns, leaving fear and loathing over the nukes to be concentrated among the plant’s Westchester neighbors (Cuomo’s backyard). Which raises the question of why in-city environmental justice groups failed to question the shutdown, which is now impeding closure of polluting “peaker” plants in their own Brooklyn, Queens and Bronx backyards. Still, the shutdown campaigners’ most grievous lapse was their failure to grasp that the new climate imperative requires a radically different conceptual framework for gauging nuclear power. New Reality #2: Wind and solar that are replacing Indian Point can’t also reduce fossil fuels.It’s dispiriting to contemplate the effort required to create enough new carbon-free electricity to generate Indian Point’s lost carbon-free output. Think 500 giant offshore wind turbines, each rated at 8 megawatts. (Wind farms need twice the capacity of Indian Point, i.e., 4,000 MW vs. 2,000, to offset their lesser capacity factor.) What about solar PV? Its capacity disadvantage vis-a-vis Indian Point’s 90% is five- or even six-fold, meaning 10,000 or more megawatts of new solar to replace Indian Point. I won’t even try to calculate how many solar buildings that would require. But this is where Indian Point’s 90% capacity factor is so daunting; had the plant stayed mired at 60%, the capacity ratios to replace it would be a third less steep. But wait . . . it’s even worse. These massive infusions of wind or solar are supposed to be reducing fossil fuel use by helping the grid phase out gas (methane) fired electricity. Which they cannot do, if they first need to stand in for the carbon-free generation that Indian Point was providing before it was shut. So when Riverkeeper pledged in 2015-2017, or Friends of the Earth’s legal director told the Guardian‘s Milman that “we are embracing renewable energy technology like solar and wind,” they’re misrepresenting renewables’ capacity to help nuclear-depleted grids cut down on carbon. Shutting a functioning nuclear power plant puts the grid into a deep carbon-reduction hole — one that new solar and wind must first fill, at great expense, before further barrages of turbines and panels can actually be said to be keeping fossil fuels in the ground. (CTC/Komanoff continued) I suspect that not one in a hundred shut-nukes-now campaigners grasps this frame of reference. I certainly didn’t, until one day in April 2020, mere weeks before Indian Point 2 would be turned off, when an activist with Nuclear NY phoned me out of the blue and hurled this new paradigm at me. Before then, I was stuck in the “grid sufficiency” framework that was limited to having enough megawatts to keep everyone’s A/C’s running on peak summer days. The idea that the next giant batch or two of renewables will only keep CO2 emissions running in place rather than reduce them was new and startling. And irrefutably true. To be clear, I don’t criticize Milman for missing this new paradigm. He’s a journalist, not an analyst or activist. It’s on us climate advocates to propagate it till it reaches reportorial critical mass. I credit Milman for giving FoE’s legal director free rein about Diablo. “There was ample notice for everyone to get their houses in order and switch over to solar and wind and they didn’t do anything,” she told him. Goodness. Everyone [who? California government? PG&E? green entrepreneurs?] didn’t do anything to switch over to solar and wind. Welcome to reality, Friends of the Earth! I knew FoE’s legendary founder David Brower personally. I and legions of others were inspired in the 1960s and 1970s by his implacable refusal to accede to the world as it was and his monumental determination to build a better one. But reality has its own implacability. The difficulty of bringing actual wind and solar projects (and more energy-efficiency) to fruition has the sad corollary that shutting viable nuclear plants consigns long-sought big blocks of renewables to being mere restorers of the untenable climate status quo. In closing: Contrary to Milman (and NY Gov. Kathy Hochul), Indian Point’s closure will wreck NY’s goal of an emissions-free grid by 2040.“Two major projects bringing Canadian hydropower and upstate solar and wind electricity will come online by 2027,” Milman wrote, referencing the Champlain-Hudson Power Express transmission line and Clean Path NY. But their combined annual output will only match Indian Point’s lost carbon-free production. Considering that loss, the two ventures can’t be credited with actually pushing fossil fuels out of the grid. That will require massive new clean power ventures, few of which are on the horizon. I’ve written about the travails of getting big, difference-making offshore wind farms up and running in New York. I’ve argued that robust carbon pricing could help neutralize the inflationary pressures, supply bottlenecks, higher interest rates and pervasive NIMBY-ism that have led some wind developers to deep-six big projects. Though I’ve yet to fully “do the math,” my decades adjacent to the electricity industry (1970-1995) and indeed my long career in policy analysis tell me that New York’s grid won’t even reach 80% carbon-free by 2040 unless the state or, better, Washington legislates a palpable carbon price that incentivizes large-scale demand reductions along with faster uptake of new wind, solar and, perhaps, nuclear. |

“Diablo Canyon has not received the safety upgrades and maintenance it needs and we are dubious that nuclear is safe in any regard, let alone without these upgrades – it’s a huge problem,” said Hallie Templeton, legal director of Friends of the Earth, which was founded in 1969 to, among other things, oppose Diablo Canyon.

“Diablo Canyon has not received the safety upgrades and maintenance it needs and we are dubious that nuclear is safe in any regard, let alone without these upgrades – it’s a huge problem,” said Hallie Templeton, legal director of Friends of the Earth, which was founded in 1969 to, among other things, oppose Diablo Canyon.

[…] Read More […]