First, the Supreme Court blows up EPA’s carbon-regulating authority under the Clean Air Act. Then Joe Manchin torpedoes President Biden’s Build Back Better package.

Climate policy is on the ropes. Is carbon pricing’s moment at hand? Can it move forward in the face of Republican opposition and Democratic indifference?

No federal legislation with a price on carbon has advanced to a floor vote since the “Waxman-Markey” American Clean Energy and Security Act cap-and-trade bill died in the Senate in 2010. Now Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), perhaps Congress’s most outspoken climate hawk, is seeking to tax manufacturers of steel, aluminum, cement and other industrial commodities to the extent that the carbon intensity of their manufacturing process exceeds U.S. averages.

No federal legislation with a price on carbon has advanced to a floor vote since the “Waxman-Markey” American Clean Energy and Security Act cap-and-trade bill died in the Senate in 2010. Now Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), perhaps Congress’s most outspoken climate hawk, is seeking to tax manufacturers of steel, aluminum, cement and other industrial commodities to the extent that the carbon intensity of their manufacturing process exceeds U.S. averages.

If coupled with a carbon border adjustment mechanism, this approach could establish a U.S. beachhead for carbon emissions pricing at the federal level. The key is its potential to benefit American industry. As Whitehouse puts it, his Clean Competition Act (S. 4355), would “give American companies a step up in the global marketplace while lowering carbon emissions at home and abroad.”

The concept resembles the European Union’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) proposal. The Clean Competition Act would charge manufacturers of widely used basic industrial commodities a fee based on their carbon emissions intensity. Firms whose carbon intensity is greater than the U.S. average for that industry would be charged, however, along with importers of goods whose carbon intensity exceeds that of its U.S.-produced counterpart.

Manufacturing and Climate Change

Industrial production is a major generator of climate change. Iron and steel manufacture is responsible for around 8% of global CO2 emissions, according to McKinsey, and aluminum production for around 2%, with cement and ammonia close behind. Current laissez-faire trade policies favor carbon-intensive imports and thus incentivize production in regions with lax emission standards, a phenomenon noted recently in a commentary in Science by 35 academics, mostly from the European Union though including a handful from the U.S. Although raw materials and intermediate goods tend to have high CO2 emissions per unit of value added, they typically face lower tariffs than more finished products with lower carbon intensities.

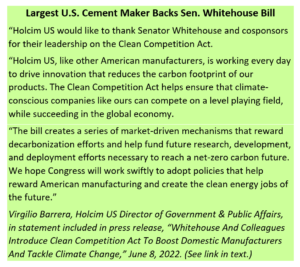

Whitehouse sees his bill as a way to use U.S. trade policy to drive climate action. He also views its potential to boost U.S. industrial competitiveness as a way to attract bipartisan support. Holcim U.S., whose parent company, Lafarge Holcim, is America’s largest cement manufacturer, supports Whitehouse’s bill.

Whitehouse sees his bill as a way to use U.S. trade policy to drive climate action. He also views its potential to boost U.S. industrial competitiveness as a way to attract bipartisan support. Holcim U.S., whose parent company, Lafarge Holcim, is America’s largest cement manufacturer, supports Whitehouse’s bill.

In its current form, the Clean Competition Act is more conceptual than prescriptive. Should it pass Congress, it will fall to the U.S. Treasury Dept. to codify regulations through administrative rulemaking, which could be complex.

U.S. industrial facilities currently report greenhouse gas emissions to EPA. The bill would use these data and also require submission of electricity use and product weight of covered goods.

So far, so good. Data reporting could be trickier for imported goods, however. Whitehouse’s bill states that, absent specific data, the carbon intensity of an imported good shall be that country’s GDP divided by its “production-based greenhouse gas emissions,” i.e., its economy’s overall carbon intensity. While country-level fossil fuel emissions and GDP data are available, translating those figures to a country’s CO2 emissions per unit of product could be contentious.

Carbon Intensities Compared

Whitehouse and colleagues argue that the U.S. economy is only around half as carbon-intensive as our trading partners’, on average — two-thirds less than China, and three-fourths less than India. While these differences hold promise for attracting domestic political support, they’re not stand-ins for industry-specific data, especially insofar as ratios for specific industrial sectors appear to be less steep.

Steel

According to a recent analysis, U.S. manufacture of steel in blast furnaces and basic oxygen furnaces (BF-BOF) is estimated to emit an average of 1.9 tons of CO2 per ton of crude steel. The respective factors for China and India are 2.1 tCO2/t and 2.9 tCO2/t. Since the U.S. also produces steel in efficient electric arc furnaces utilizing scrap metal, these differences may understate the U.S. advantage. Another study, by the Climate Leadership Council (CLC), found that indeed, the prevalence of electric arc furnaces, the relatively low carbon footprint of U.S. electricity production, and a greater reliance on natural gas rather than coal give U.S. steel production a significant advantage over virtually all major trading partners.

Aluminum and other commodities

U.S. aluminum manufacturers also fare well, with an average carbon intensity of just under 8 tCO2/t vs. nearly 13 tCO2/t for China and 15.5 tCO2/t for India. With cement, however, U.S. production is less energy-efficient on average than in China and India, which have newer factories. However, those countries’ greater coal-dependence for electricity generation may tip the carbon intensity scale in favor of the U.S. For ammonia, the U.S. is likely less carbon-intensive than coal-reliant China, which emits an estimated 45% of that sector’s worldwide CO2 emissions while producing only 30% of the product.

Another factor to consider in evaluating the performance of U.S. industry vs. trading partners is the country of origin. According to the USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries, most U.S. steel imports come from Canada, Brazil and Mexico, while most of our imported cement comes from Canada and Turkey, and most of our imported aluminum from Canada.

Still, China dominates world production of steel, and if CBAM should become established with the European Union or, better yet, with a “climate club” including the U.S., Canada, the UK, the EU and Japan, China’s CO2 emission liability could motivate it to reduce its emissions rather than be disadvantaged in international markets.

Outlook

Could America’s overall carbon superiority over our trading partners help Sen. Whitehouse’s Clean Competition Act attract support from House and Senate Republicans? Climate Leadership Council V-P Catrina Rorke, in a June 13 presentation to Citizens’ Climate Lobby members, cited interest among Republican senators in connecting trade and greenhouse gas emissions. In an August 2021 letter to President Biden, 19 G.O.P. Senators led by Kevin Cramer (R-ND) and Dan Sullivan (R-AS) called on the U.S. to work with EU and other trading partners to design a common approach to climate and trade policy.

While bipartisan action would fly in the face of a dozen years of untempered Republican opposition to climate policy, Sen. Whitehouse is to be commended for pursuing his novel approach. For the climate’s sake, let’s hope his efforts aren’t unrequited.