Janet Yellen, chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, 2014-2018, and president-elect Biden’s apparent choice for Treasury Secretary, quoted in The 41 Things Biden Should Do First on Climate Change, Bloomberg Green, Nov. 11, 2020.

The time of fossil fuel subsidies is over. Coal must be phased out. Carbon should be given a price. 2021 must be the year of a great leap towards carbon neutrality.”

UN Secretary-General António Guterres, via Twitter, Nov. 16.

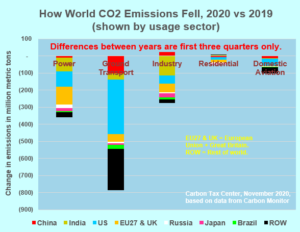

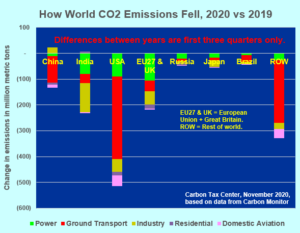

Downturn in U.S. driving led 2020 global CO2 decline

[Note: A Feb. 23 update to this post with full-year 2020 vs. 2019 data for all eight world sectors revised, downward, the shrinkage of U.S. ground transport carbon emissions that we had highlighted here. That revision is substantial.]

The world’s emissions of carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels diminished by more than 1.6 billion metric tons in the first three quarters of 2020 from the same period in 2019, a decline of 6.3 percent. Fully one-fifth of the decline, 320 million tonnes, was due to the nearly 25 percent drop in ground transport in the United States, according to data compiled and made available this week by Carbon Monitor, an international collaboration of energy and climate specialists providing regularly updated, rigorous estimates of daily CO2 emissions.

The Carbon Monitor data, downloaded and reshuffled by Carbon Tax Center, reveal the sources and extent of the drop of emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic. In both absolute and percentage terms, the total U.S. year-on-year January-September decline — 514 million metric tons and 13.1 percent — outpaced the world’s other major emitting nations and regions. The percentage drop of 13.1 percent through September more or less guarantees that U.S. carbon emissions for all of 2020 will fall below year-2019 emissions by double digits.

The Carbon Monitor data, downloaded and reshuffled by Carbon Tax Center, reveal the sources and extent of the drop of emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic. In both absolute and percentage terms, the total U.S. year-on-year January-September decline — 514 million metric tons and 13.1 percent — outpaced the world’s other major emitting nations and regions. The percentage drop of 13.1 percent through September more or less guarantees that U.S. carbon emissions for all of 2020 will fall below year-2019 emissions by double digits.

Close behind the United States in percentage terms of decline were Brazil, with a 12.9 percent drop from 2019 to 2020, and India with 11.7 percent. But because U.S. emissions are so large in absolute terms, the tonnage drop here dwarfed that of India (225 million tonnes) and Brazil (44 million tonnes).

China was far down the ranks of emission reducers. From the first three quarters of 2019 to the same period in 2020, its emissions shrank by just 109 million tonnes, a decline of only 1.4 percent. Although China’s ground transport carbon emissions did fall by 15 percent — just short of the rest of the world’s 16 percent decline for that category — none of the country’s other major emitting sectors showed pronounced declines, except for domestic aviation, which fell by 26 percent. Omitting China from the calculations, world CO2 emissions fell by 8.4 percent over the three-quarter periods, though admittedly that construct is a bit like considering recent U.S. presidential popular votes without California.

Nearly half of the global CO2 decline — 787 million tonnes out of the overall 1,621 million tonne drop — was accounted for by reduced ground transport emissions. With truck traffic probably little affected by the pandemic, as indicated by the mere 3.4 percent drop in world carbon emissions from industry, the decline presumably is attributable to decreased use of passenger vehicles. The reduction in aviation emissions was even more pronounced, at 36 percent, as many air travelers deemed it unwise to spend hours in confined aircraft spaces, and teleconferencing filled in for most business travel. The reduction rate might have been higher still, but for “ghost flights” resulting from byzantine government regulations and financial incentives.

There’s something satisfying in seeing year-on-year carbon emission figures in negative-land, even as we can’t deny the enormous human and social suffering that not only accompanied but to an extent delivered the reductions. A global pandemic causing over 1.3 million deaths and rising, according to the count maintained by Johns Hopkins University, and stunting child development as “remote learning” replaces in-person schooling, to name but one societal forfeiture, is not the path anyone would choose to curb climate-wrecking use of fossil fuels.

Perhaps we could look to the European Union, which pulled off a nearly 14 percent drop in carbon emissions from power generation, accounting for an absolute reduction of 105 million tonnes thus far in 2020 vs. 2019. In contrast, Carbon Monitor’s “Rest of World” group — encompassing all countries other than China, India, USA, Russia, Japan, Brazil and the EU — shaved only 1 percent from its power generation emissions, a decrease of just 27 million tonnes from 2019 emissions of 2,775 million tonnes. A deep dive into the disparate reductions might be useful for devising abatement strategies going forward.

This post only skates the surface of the data made available by Carbon Monitor. Their downloadable Excel file comprises some 36,000 entries: CO2 emissions for every 2019 and 2020 day (Jan-Sept) for five categories by eight countries or regions (some rows capture individual European countries: France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK). The daily data provide a quantitative window into that terrifying but bracing springtime period when lockdowns pushed emission rates in the US and other countries 20 or even 40 percent below year-earlier levels. The CM graphics (same link as above) are marvelous as well, as is an Oct. 14 article in Nature Communications by three CM staff distilling and interpreting their quantitative findings.

The second bar graph was added on Nov. 24. Drop us a line (email here) to share your own excavations of the Carbon Monitor data, or if you’d like us to send you our spreadsheet distilling CM’s data as used in this post.

The G.O.P. senators to target for a carbon tax

Addendum two years on, to note today’s NY Times story, 12 Republican Senators Who Crossed Party Lines (print edition), with its dozen tales of G.O.P. independence and a modicum of political bravery in bucking Republican party-line homophobia to vote for the Respect for Marriage Act, which Pres. Biden signed on Dec. 13. The dozen were these nine: Capito (WV), Collins (ME), Ernst (IA), Lummis (WY), Murkowski (AS), Romney (UT), Tillis (NC), Sullivan (AS) and Young (IN); plus three who are retiring: Blunt (MO), Burr (NC), and Portman (OH). The nine still in the Senate should be top of mind for carbon tax advocates looking for bipartisan Senate support. — C.K., Dec. 14, 2022.

As I was writing this post, I saw on Twitter that not a single sitting Republican U.S. senator accepted an invitation to appear on Meet the Press today. Though that could mean many things, the refusal of the entire G.O.P. senate conference to be interviewed by the pre-eminent Sunday mainstream media talk show bodes poorly for productive policy and political dialogue going forward.

What makes Republican intransigence especially disheartening is that even if the Democrats manage to defy the odds and capture both seats in Georgia’s Jan. 5 U.S. Senate elections, giving them a one-vote majority by virtue of the vice-presidential tie-breaker, they may still need Republican votes to pass impactful climate legislation in the next Congress.

Those votes could offset a possible No vote by one of the Democrats’ own: Joe Manchin, a legislator best known for a 2010 campaign video in which he fired a bullet through a handbill promoting the Democrats’ carbon cap-and-trade bill “because it’s bad for West Virginia.” The Mountaineer State is famously coal-dependent and pro-Trump. Only 30 percent of voters there chose Biden on Nov. 3, his lowest share in any state except Wyoming. And Manchin is up for re-election in 2022.

Like it or not, her state’s climate-energy-electoral profile and her own relative centrism make Maine’s Susan Collins the most likely Republican senator to consider meaningful climate measures such as a carbon tax. Photo courtesy Susan Collins for Senator.

Sen. Manchin may not be the only Democratic senator turning his back on climate legislation when Congress convenes in January. Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema began her political career with the Green Party but has since tacked right. Her senatorial voting record last year was even more conservative than Manchin’s, according to GovTrack’s “Ideology Score.” Since she’s not up for re-election till 2024, she could decide that she would have time to recoup from a pro-climate vote.

Georgia aside, then, any climate bill worthy of the name may need Republican votes to clear the Senate. Is there any prospect of getting even a single G.O.P. senator to vote for, say, a revenue-neutral carbon tax like fee-and-dividend — a measure that wouldn’t expand government and thus might be considered “on brand” with traditional Republican principles, as we noted in a post here the day after the election?

Hard experience with the Republican conference over the past dozen years would suggest no. On the other hand, inexorably rising climate concern and the growing call for climate action point to at least a possibility that a few G.O.P. senators might see it in their interest to stand down Mitch McConnell and defect from his party’s deflect-and-deny strategy.

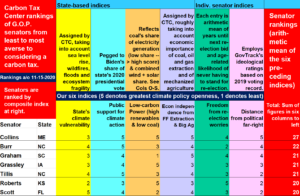

CTC’s ranking system for senatorial climate-openness

We’ve ranked the 52 Republican incumbent and incoming senators (that’s this month’s 50 G.O.P. winners plus Georgia’s Perdue and Loeffler) by their openness to climate legislation. We made six indices — two pegged to each state’s fossil fuel dependence, two reflecting its sensitivity to climate chaos, and two denoting senators’ individual insularity from pro-fossil-fuels political pressure. We developed 1-to-5 scales for all six criteria and scored the senators on each. The maximum possible score was 30, and the lowest was 5.

And the highest scorer is Susan Collins, whose upset victory on Nov. 3 will vault her to a fifth term. Our ranking system gives her 27 points: 5 (the maximum) for Maine’s low coal dependence and high use of renewables, for its independence from fossil fuel extraction and carbon-intensive Big Agriculture, for the state’s high (among states with Republican senators) vote share for Joe Biden, and for what we call distance from the far right (Collins’ 2019 GovTrack score was the most liberal among G.O.P. senators; plus a score of 3 for Maine’s climate vulnerability; and a 4 for what we term freedom from re-election worries — Collins has six years before her re-election comes ’round again. Although she’s 68, that’s not much more than the Republican senatorial average age of 63, giving Collins a relatively low “lame-duck likelihood” based on age-related retirement.

At the bottom of our scale, with scores of 10, are a couple of senators from primo American fossil fuel sacrifice zones: Kevin Cramer of North Dakota and John Barrasso of Wyoming. Both states place below-average in climate vulnerability, low in climate concern, high in coal burning and energy extraction generally, and frustratingly mediocre in deploying wind and solar. Moreover, both senators sport far-right voting records and are just in their 50s, making them good bets to stand for re-election when their terms end in 2024. (We won’t belabor the fact that ND and WY rank 47th and 50th in population, and that their combined population, just 1.34 million, is less than half of one percent of the total U.S. population of 330 million.)

Collins’ 27 score leads her conference by far, suggesting that carbon-tax and other pro-climate advocates should be targeting her heavily. If her state’s Democratic tilt, independence from coal and fuel extraction and Big Ag and relatively high deployment of renewables, along with her relative centrist leaning and six-year window before facing the voters again, won’t incline her toward supporting climate legislation, it’s hard to picture any other Republican senator going that way.

These six are next:

♦ Richard Burr (NC), 22 score, on account of NC’s high climate vulnerability (think Outer Banks), relatively high Biden vote and relative independence from fuel extraction and Big Ag, as well as Burr’s own distance from the extreme right. On the down side, he’s up for re-election in 2022.

CTC’s seven leading scorers. Follow link at end of post to download Excel file with all 52 senators and the underlying raw data.

♦ Lindsey Graham (SC), 21, due to the state’s low economic dependence on fuel extraction and Big Ag, his relative distance from the far right, and the fact that his seat is secure till 2026.

♦ Charles Grassley (IA), 21. Advocates who subscribe to Vox columnist Dave Roberts’ thesis that a robust renewables sector must precede climate legislation should target Grassley on account of his state’s huge wind industry (the country’s largest, percentage-wise). Plus, at age 87, his 2022 re-election campaign will probably be his last.

♦ Tom Tillis (NC), 21 — yep, the guy who just withstood a strong challenge from Democrat Cal Cunningham. Tillis’s profile is similar to that of fellow North Carolinian Richard Burr, with greater insulation from political opposition but a more right-wing voting record, according to GovTrack.

♦ Pat Roberts (KS), 20. Fresh off re-election, the 84-year-old Roberts should be immune to electoral pressure. His other big plus is Kansas’ vibrant wind sector, second only to that of Iowa in percentage terms.

♦ Rick Scott (FL), 20. The Sunshine state’s stark vulnerability to sea-level rise, along with its relatively high Biden vote share (48%) and its lack of fossil fuel production, give it high relative potential. (Fellow FL Senator Marco Rubio scored less, 18, due to his pending 2022 re-election campaign.) Sadly, Florida’s failure to live up to its nickname where energy production is concerned holds back both senators’ likelihood of going pro-climate.

Notably absent from the top ranks is Utah Senator Mitt Romney, who earlier this year defied both President Trump and Leader McConnell by voting to convict the president of impeachment — the lone Republican to do so. Romney scored just 15, slightly below the sample average of 16. Utah ranks high in fuel extraction, and the state’s electricity sector is almost twice as coal-dependent as the average for other Republican senators — factors probably reflected in Romney’s outspoken support for the state’s oil, gas and coal industries. Further hurting Romney’s score was Utah’s low Biden share, 38%. The same dynamics along with a pending 2022 re-election campaign resulted in a middling 18 score for another ostensible Republican maverick, Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski.m, despite her state’s extreme vulnerability to climate damage.

You may have noticed that our rankings omit personal political preferences. Who knows, perhaps Romney’s courage on impeachment could signal willingness to break with McConnell on climate. Similarly, as we wrapped this post we got word that Indiana Sen. Mike Braun, who like Romney received an undistinguished 15 score, has volunteered to co-lead the U.S. delegation to the next U.N. COP (Coalition of the Parties) global climate meeting in Glasgow next November. Clearly, our rankings are far from all-inclusive, but hopefully they can be useful as a screening tool.

The major takeaway here is that in addition to working to elect Georgia Democrats Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff to the U.S. Senate, climate campaigners need to start focusing their resources to move Republican senators to act on climate in the new Congress.

Link to the CTC rankings spreadsheet: http://www.komanoff.net/fossil/GOP_Senators_Ranked.xlsx.

This post was updated on Nov. 16 to include a sentence about Senator Murkowski.

They should get out the vote in Georgia because Biden has just shown us what’s possible there. That’s what will make climate action possible. Forget the whole question of compromise. That’s not even an option right now. Even if you only want ‘incremental progress,’ you’re not going to get it without a Democratic senate.”

Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communications, quoted in Inside Climate News, With Biden’s Win, Climate Activists See New Potential But Say They’ll ‘Push Where We Need to Push’, Nov. 8.

Razor-Thin Election Could Boost Carbon Tax. But What Kind?

Could a carbon tax emerge from the U.S. elections? Quite possibly.

The apparent results — a narrow Biden win coupled with continued Republican control of the Senate — do not bode well for the Investment and Justice legs of the climate left’s ambitious “S-I-J” triad. Many elements of the third leg, Standards, can be enacted through executive orders (e.g., restoring auto mileage and other efficiency regulations eviscerated by the Trump administration). Not so the Green New Deal components such as large-scale federal investment in renewables, mass transit and sustainable communities.

It could be, however, that a carbon price could qualify as a rare climate measure palatable to enough Republicans to make it into legislation next year.

“Divided control of government will likely not yield a wealth tax, progressive taxation or Green New Deal-style policy,” NY-based political strategist Neal Kwatra wrote today, and we agree. Republicans will not bend in protecting extreme wealth. They also disdain a GND, not just on account of its identification with Justice Democrats standard-bearer Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez but because it harkens to an era in which muscular, compassionate government went to bat for the common good. While it doesn’t necessarily follow that Republicans will accede to taxing carbon emissions — the G.O.P.’s climate stance long since ossified into deflection and denial — a carbon tax could become the party’s way to bow to political and demographic reality and finally signal a modicum of climate concern.

As readers of this blog know, it has become increasingly clear to us that, standing alone, a carbon tax has become too fraught politically and too weak economically to serve as the centerpiece of U.S. climate policy. We concluded last year that the path to decarbonizing the U.S. economy lay in Green New Deal-inspired infrastructure and investment funded by taxes on extreme wealth and supported by a carbon tax.

We envisioned a three-part program to accomplish this:

- A Green New Deal plan investing 10 to 20 trillion dollars over a 10-year period to develop the infrastructure, industrial capability, and consumer incentives to quickly decarbonize the U.S. energy system.

- New taxes on extreme wealth and financial transactions, supplemented by increases in estate taxes, marginal income tax rates, capital gains and corporate taxes, to generate, from the wealthiest American households, the funds needed to pay for the Green New Deal.

- A rising charge on carbon emissions from fossil fuels that would support the Green New Deal by shortening payback periods for green investment and inculcating energy efficiency and conservation throughout American society.

The Democrats’ apparent failure to capture the Senate will almost certainly put #1 and #2 on hold at least till the 2022 midterms — and probably beyond, given the strong tendency of the ruling party to shed Congressional seats in off-year elections. Not only that, divided government will make it much harder for a Biden administration to push through the progressive changes in areas like health care and racial equity that might have created political capital to pass elements of the ambitious program sketched above.

Nevertheless, the relentless rise in jobs in clean energy coupled with the long-term shrinkage in fossil fuel industry employment might reduce the political cost to some G.O.P. senators to act on climate. If so, a carbon tax, especially a revenue-neutral one that sends the carbon revenues to households rather than government, would be somewhat “on brand” with traditional Republicanism — if there is still such a thing.

Needless to say, the persistence of the Republican Senate majority means that the filibuster remains, markedly complicating the legislative path to a federal carbon tax. (Molly Reynolds of the Brookings Institution recently posted an excellent primer on the filibuster with a section devoted to “the budget reconciliation process” which allows a simple majority to adopt certain bills addressing spending and revenue provisions, thereby circumventing the filibuster.)

But if events do break in the direction of pricing carbon emissions, climate advocates had better stand tough for a strong carbon tax. Not the $20 per ton of CO2 that Exxon occasionally bandied about during Obama’s presidency. And probably not even the $40/ton tax promoted by the Climate Leadership Council, unless the council can be persuaded to increase its preferred 5% real annual rises which would tack on just a few dollars each year following that initial jolt.

No, a carbon tax worth fighting for has to hit triple digits before long, say, by year six or seven. That’s the trajectory that can drop emissions by a third in a decade and that would be a worthy template for other major emitting countries, allowing the U.S. action to ripple productively around the world.

A carbon tax centering U.S. climate policy is the outcome we sought when we founded CTC at the start of 2007. Nearly fourteen years on (and largely squandered by Republican obstructionism), a carbon tax by itself isn’t enough to stave off climate hell. But it’s still well worth fighting for.

Blame the NIMBYs *And* Exxon

(A slightly shorter version of this post first appeared in Streetsblog NYC on Oct. 28.)

My neighborhood NIMBY’s (Not In My Back Yard-ers) are at it again, this time slapping down a bid by the Tribeca Whole Foods to install a cargo bike loading dock in front of their Tribeca store in lower Manhattan.

Delivery bicycles with trailers outside a Whole Foods in Brooklyn, NY. Manhattan stores need loading space in the street to avoid foot traffic and narrow sidewalks.

As Streetsblog reported last week, the executive committee of Manhattan Community Board 1 voted 6-4 to shelve the plan. So it’s back to the drawing board, meaning, at best, needless delay of a rare Mayor de Blasio-approved initiative to unclog our streets and reduce truck emissions by using human-powered delivery bikes, some with electric assist, for urban “last-mile” delivery. (For those of you possibly seduced into imagining Bill de Blasio is a climate mayor, think again.)

One board member said that giving up five free-parking spaces to accommodate the loading area would be “a travesty.” The vote, and the contentious and largely uninformed discussion preceding it, showed the folly of allowing unelected community boards veto power on innovations that could help move people and goods safely and sustainably. It also laid bare the hollowness of the “just blame Exxon” narrative that has taken hold of the climate movement.

Listen to the committee meeting and three objections emerge:

- Reserving a patch of curb for cargo bikes is placard corruption redux (timecode 10:58).

- Except when it’s a giveaway to the world’s richest person (10:35 and 22:15).

- And, the kicker, Fresh Direct food-delivery trucks pollute (26:50).

Wait, what?

“Twenty-four hours a day,” one exec-committee member hyperbolically reminded the Zoom gathering, prior to casting his No vote, “Fresh Direct has a series of trucks parking [in Tribeca and] spewing diesel emissions… We’re doing the same thing now with Whole Foods.”

You read that right: in the mind of this self-proclaimed automobile and motorcycle aficionado, idling Fresh Direct trucks elsewhere in Tribeca are a reason to deep-six a competitor’s scheme to swap out polluting trucks with zero-emission cargo bicycles. (That logic brings to mind that old New York Times story about a proposed wind farm near Cooperstown in which some rando whined that seeing giant windmills near his house “would be like driving through oil derricks to get to your front door,” a story I mentioned in my long-form article on wind power back in 2006.)

From the same committee member: “The streets have gotten more dangerous because they have not been widened… There are so many uses that [NYC] DOT is trying to provide for: commercial, vehicular, buses, bike lanes, new pedestrian areas — they’re painted in such a way it looks like someone on psilocybin did the layout. It’s so confusing and dangerous with the various modalities interacting with each other and [cargo biking] is just one more… To me this whole concept is objectionable and it’s not because I necessarily drive more than anyone else, it’s just enough … enough input on our streets!” (It starts at 29:20.)

There it is: The streets are dangerous because government, seeking to advance traffic safety and efficiency, has made it trickier for me to wield my dangerous vehicle. And now you’re doing it again. Take your government hands off my government-subsidized driving and free parking!

The episode lays bare some discomfiting truths. For one, America’s extreme economic inequality not only gives plutocrats like Whole Foods and Amazon owner Jeff Bezos immense reach into our lives, it also provides a pretext to oppose any positive steps rich people might take, under the guise of progressivism. For another, placard abuse — illegal appropriation of curb space by police and other public employees’ private cars, a practice that is rampant in New York City, especially lower Manhattan — serves as a convenient cause to reject any measure to reconfigure curb space; so long as cops and other apparatchiks get free parking, “the community” deserves no less.

But here’s another disconcerting truth: we can’t simply deem Exxon and its fellow fossils solely responsible for the climate crisis if unelected NIMBY’s are able to delay, water down or block seemingly every path to actually cut carbon emissions.

Last week, in addition to the no vote at Manhattan Community Board 1, there was the district manager of Queens CB1 demanding that some Citi Bike docks in Astoria be relocated from the roadbed to the sidewalk, a change that cycling advocates rightly fear would impede traffic calming in the area. On this “livable-news,” urbanite site (Streetsblog), probably a tenth of all posts since its founding in 2006 have concerned pushback by NIMBY’s on Brooklyn’s Prospect Park West (bike lane), Manhattan’s 14th Street (bus lane) and other thoroughfares throughout the five boroughs that has forced “livable-streets” advocates to wage protracted battles for bike lanes, bus lanes and a citywide array of life-saving speed cameras. More broadly, scarcely a day goes by that somewhere in the 50 states, a carbon-busting wind farm, solar array, infill housing or transit project is turned aside or left off the drawing board altogether on account of obstruction from deep-pocketed, aggrieved Not-In-My-Back-Yard types.

Yes, Exxon’s political muscle and support of denialist think tanks have for decades helped enforce pro-carbon stasis. Ditto, the Koch Brothers’ “dark money,” as copiously documented by diligent reporters like Jane Mayer and Christopher Leonard. But the oil and gas industry only retains its power because demand for its products persists.

Yes, Exxon’s political muscle and support of denialist think tanks have for decades helped enforce pro-carbon stasis. Ditto, the Koch Brothers’ “dark money,” as copiously documented by diligent reporters like Jane Mayer and Christopher Leonard. But the oil and gas industry only retains its power because demand for its products persists.

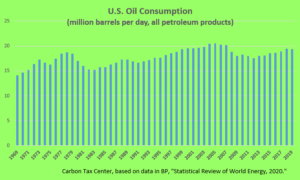

After Joe Biden pledged during the second and final presidential debate to “transition away from the oil industry,” Politico’s Tim Alberta tweeted (and MSNBC’s Chris Hayes retweeted) that “we’ve been transitioning from oil for 50 years.” Dream on. Until the pandemic, U.S. vehicle-miles traveled stayed high, SUV’s and pickups kept ballooning, and air travel grew steadily — trends reflected in the chart above.

Stopping NIMBY’s from holding up low-carbon alternatives isn’t the whole struggle, but it’s a big part. I’m told that a reconfigured cargo-bike resolution could come before Manhattan CB1 as early as next Thursday, Nov. 5. Unless I’m in the streets demonstrating for election integrity, I plan to attend.

Full disclosure: the writer owns Amazon stock, giving him a financial interest in Whole Foods.

Carbon-Tax Expert: Chase Opportunity, Not Compliance

Perhaps you saw our recent point-counterpoint dissection of Matto Mildenberger and Leah Stokes’ Boston Review article, The Trouble With Carbon Pricing. Both authors, political scientists at the University of California’s Santa Barbara campus, published books on climate policy this year — Carbon Captured: How Business and Labor Control Climate Politics (Mildenberger), and Short Circuiting Policy: Interest Groups and the Battle Over Clean Energy and Climate Policy in the American States (Stokes). Stokes has gained a devoted following in the climate movement for the flair with which she articulates a “standards-investment-justice” policy frame that relegates carbon taxing and other so-called “market mechanisms” to at most a subsidiary role.

Niskanen Center’s Joseph Majkut. “With carbon pricing, the private sector will be chasing opportunity instead of compliance.”

In our post we rebuffed that “market mechanism” label. “Taxing carbon emissions has nothing to do with ‘markets’ and everything to do with fixing the enormous market failure that allows fossil fuel companies and monster-truck drivers and frequent flyers pay zero for climate pollution,” we wrote. We also called on the climate movement to “harness the growing fury at the ever-expanding wealth gap with a program to tax both extreme wealth *and* carbon emissions and invest the proceeds into the Green New Deal” — a program we outlined last year.

Now comes the Niskanen Center’s climate policy director Joseph Majkut with his own response to Mildenberger and Stokes (M&S). Befitting the center’s standing as a politically grounded policy shop, The Immediate Case for a Carbon Price is savvy and compelling.

Whereas M&S largely dismiss carbon pricing as too chancy and slow to deliver large-scale low-carbon infrastructure, Majkut contends that pricing will bear fruit more quickly than regulations mandating and investment:

A carbon tax will start working almost immediately and be on solid legal ground, while complex regulations will take years for government agencies to craft and defend in court. If immediacy is necessary, then a carbon price is our best tool. (emphasis added)

Majkut also argues that the policies M&S tout, such as low-carbon procurement or production standards, targeted tax credits and expanded R&D, “will be more effective in a world where carbon pricing is a certainty.”

“Regulatory predictability and market certainty come from a carbon price,” he writes, “not from continually changing command-and-control measures.” With carbon pricing, he insists, “The private sector will be chasing opportunity instead of compliance.”

That last point resonates strongly with us. In an earlier (2012) point-counterpoint with Vox’s David Roberts (then at Grist), we wrote that “Standards and regulations tend to motivate threshold-meeting behavior but no more,” whereas the impacts of carbon pricing are unconstrained by this or that limit. In effect, raising the price to burn carbon imbues every fossil fuel-using process, decision or investment with a newly profitable opportunity to use less. Skeptics of the power of carbon pricing tend to overlook this dynamic, in keeping with their focus on Big Oil and their relative indifference to individuals’ role in fuel use and carbon burning.

That last point resonates strongly with us. In an earlier (2012) point-counterpoint with Vox’s David Roberts (then at Grist), we wrote that “Standards and regulations tend to motivate threshold-meeting behavior but no more,” whereas the impacts of carbon pricing are unconstrained by this or that limit. In effect, raising the price to burn carbon imbues every fossil fuel-using process, decision or investment with a newly profitable opportunity to use less. Skeptics of the power of carbon pricing tend to overlook this dynamic, in keeping with their focus on Big Oil and their relative indifference to individuals’ role in fuel use and carbon burning.

Here are more bon mots (actually, well-chosen sentences) from Majkut’s post, following by a few dissents.

- U.S. goods are 80 percent more carbon-efficient than the world average. If that difference were recognized in prices, U.S. manufacturers would have an immediate competitive advantage and the incentive to build upon it.

- Price signals are a major pull for innovation. Carbon pricing is a path to technology-neutral clean energy innovation and will spur investment in new technologies.

- Congress has the constitutionally articulated power to lay and collect taxes. Even the most conservative judiciary will be hard-pressed to find a constitutional objection to levying an excise tax on carbon dioxide emissions.

- Even before affecting home heating bills or prices at the pump, future tax obligations from the carbon price would drive investment decisions for every power plant, factory, and pipeline in favor of low-carbon alternatives.

- Carbon pricing is fairly popular when framed as a tax on fossil fuel polluters for the damages caused by their products. The Yale Climate Opinion maps show that 68 percent of Americans favor making fossil fuel companies pay for carbon in their products.

- M&S are right that economists’ dreams of solving the climate problem with carbon pricing alone have not materialized anywhere. However, even if policymakers are not willing to rely on pricing alone, it is clear that almost any conceivable set of standards and regulations would operate more rapidly and efficiently if combined with a carbon price.

- M&S write that “[c]arbon pricing has dominated conversations around climate policy for decades, but it is ineffective. Only a bold approach that centers politics can meet the problem at its scale.” I argue that as soon as we are having an actual conversation about imposing a climate policy that meets the problem at its scale, a carbon tax will live.

Where CTC differs from Niskanen

- Much of the business community, including a sizable portion of the fossil fuel industry, now favors climate action via carbon pricing. The remaining encampments of climate denial are shrinking both in industry and government… The denial apparatus that formerly united the fossil fuel industry with their political allies is losing members as the coal industry shrinks, and the oil industry supports carbon pricing. Yes, that climate denial is shrinking, No, that the fossil fuel industry has come to favor carbon pricing. A few oil companies may have signed on to the Climate Leadership Council’s blueprint with a $40 per tonne of CO2 carbon price, but neither the blueprint nor the signatories have committed to the kind of robust price-per-ton increases needed to do the heavy lifting of deep decarbonization. Moreover, initialing a policy paper is a far cry from putting political muscle behind legislation. Count us as deeply skeptical that any fossil fuel company will ever embrace meaningful carbon pricing.

- [The standards] approach will have to resemble California’s, with a complex mix of policy instruments to reduce emissions from transportation, homes and buildings, and industry. While that state is making substantial progress toward its renewable energy goals, it stands to miss its climate targets. Those targets are far more ambitious than any other state’s. Indeed, as we reported last year, for decades California has far outpaced the other 49 states in shrinking its use of fossil fuels relative to economic output, so much so that U.S. emissions would now be nearly 25 percent lower if the entire country had kept pace. Majkut also missed an excellent chance to cite the NBER working paper that found that California’s cap-and-trade program has significantly shrunk the state’s “environmental justice gap.”

- A plan based on standards, investments, and justice may help build a left-wing coalition, or even pass in California or a few East Coast states. But at the national level, it will require significant new regulations, funding, and administrative capacity. Majkut’s link is to David Roberts’ affirmative post for Vox earlier this year, “At last, a climate policy platform that can unite the left,” that laid out the standards-investment-justice (S-I-J) triad that undergirds M&S’s article. In our opinion, he does both Roberts and M&S a disservice by labeling it left-wing. Indeed, the entire thrust of Roberts’ post, voiced in its subhead, is that “The factions of the Democratic coalition have come into alignment on climate change.” Not just the leftier parts, but every component of the Democratic Party, including centrists, labor and people of color.

It’s not surprising or even disconcerting that the center-right Niskanen Center would find fault with a center-left standards-investment-justice climate policy frame that disses carbon pricing. At CTC we’re still striving for a policy synthesis that combines S-I-J with carbon pricing, along the lines we sketched in our midsummer post, If the Democrats run the table in November. Unlike Mildenberger and Stokes and, evidently, Majkut and Niskanen, we don’t wish to choose between the two.

That said, Majkut’s post is a worthy and welcome counterweight to the naysaying about carbon taxing that has come to be de rigeur for the climate left. We invite everyone engaged in climate advocacy and interested in carbon pricing to give it a good read.

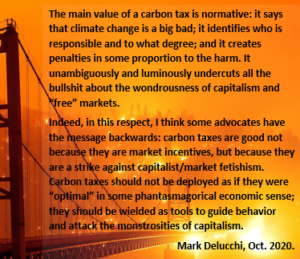

The main value of a carbon tax is normative.

Background image: Birdwell Bar Bridge over Lake Oroville, CA, Sept 2020.

Of the dozens of replies to our two latest posts — last week’s tutorial about carbon pricing’s success in narrowing California’s “EJ gap” and this week’s appeal to climate hawks to stop disparaging carbon pricing and instead welcome it as a pillar of climate policy — the one that struck with the greatest force was this message shown at right from U-C Berkeley cost-benefit analyst Mark Delucchi.

Mark, you could say, is a heavy hitter. Starting around 1990 he gained renown for his monumental work cataloguing and quantifying the societal costs of U.S. motor vehicle use. This 1996 article in the University of California Transportation Center’s Access journal only hints at the range and erudition of that immense project, but is nevertheless a good introduction to Mark’s work.

He later teamed up with Stanford civil and environmental engineering professor Mark Z. Jacobson to generate an equally prodigious series of “roadmaps” outlining, at the state, national and global levels, the logistics and benefits of converting the world’s energy systems entirely to “100% wind, water and sunlight.” For a compelling and accessible entree to that body of work see this 2016 article in Science Direct.

Mark’s message about carbon taxing, which I’ve lifted from an email he sent, speaks for itself. I’m particularly drawn to his appeal to deploy carbon taxes not in specious pursuit of absolute economic efficiency, but to guide behavior.

Of late, among the left it has become fashionable — obligatory, even — to denigrate carbon pricing as a neoliberal “market measure” and to dismiss the quest to enact carbon taxes as, at best, a misguided distraction, or, at worst, a means of further subjugating oppressed peoples. Mark’s framing underscores that carbon taxes are more truly the opposite: a tool with which to attack predatory capitalism and aid in the struggle for a just and sustainable world.

The Unique Power of Carbon Taxes? These Climate Hawks Are Missing It

Pricing carbon pollution brings out the knives. In 2009, right-wing denialists scuttled the ambitious Waxman-Markey bill by carving up its cap-and-trade centerpiece. In 2016, lefty ideologues like Food and Water Watch butchered what would have been a groundbreaking Washington state carbon tax.

Now comes a new twist: attacks from brainy pro-climate types like activist-scholar Leah Stokes, poli sci professor at the University of California’s Santa Barbara campus and a popular climate commentator on progressive media.

Stokes let loose last month with a broadside: The Trouble With Carbon Pricing, an extended essay in Boston Review co-written with her departmental colleague Matto Mildenberger. “Carbon pricing has dominated conversations around climate policy for decades, but it is ineffective,” intoned the subhead. “Only a bold approach that centers politics can meet the problem at its scale.”

Calling carbon taxing ineffectual is odd, when it’s barely been tried, and never at the triple-digit level ($100 or more per ton of carbon dioxide) that could slash emissions by a third or more. As we show below, the Mildenberger-Stokes article holds carbon pricing to a standard — closing down the U.S. and world fossil fuel sectors in a few decades — that no stand-alone policy could possibly meet. Their article also stereotypes carbon tax proponents as blinded by carbon pricing’s elegance, when what dazzles many of us is its potential to yield deep emission cuts while also neutering the fossil fuel companies.

Nevertheless, Mildenberger and Stokes have thrown down the serious gauntlet of whether carbon pricing should be the centerpiece of climate organizing and legislating. Their article is also useful for assembling so many criticisms of carbon pricing in one place.

To hold their article up to the light, we’ve posted key excerpts, with our responses alongside. (NB: except for the section heads, everything in the left column is quoted verbatim.)

The trouble with carbon pricingBy Matto Mildenberger & Leah C. Stokes, Boston Review 1. Carbon pricing isn’t working in California. Over a decade ago, California put a price on carbon pollution. At first glance the policy appears to be a success: since it began in 2013, emissions have declined by more than 8 percent. Today the program manages 85 percent of the state’s carbon pollution: the widest coverage of any policy in the world… But while the policy looks good on paper, in practice it has proven weak. Since 2013 the annual supply of pollution permits has been consistently higher than overall pollution. As a result, the price to pollute is low, and likely to remain that way for another decade… This is not a surprise. Though legislators aimed to tighten the law in 2017, oil and gas lobbyists thwarted their efforts. One powerful labor union initially supported ending free permits for big polluters, but reversed its position after Chevron offered it a union contract to retrofit refineries. The final legislation prohibited enacting new regulations on California’s fossil fuel industry — regulations that could have done more than the state’s weak carbon price.  CTC director Charles Komanoff was lead author of this report lauded by M+S. Rather than carbon pricing, other regulations — clean electricity standards, clean car programs, and aggressive energy efficiency — deserve much of the credit for the state’s progress. |

Why carbon taxes still matterBy Charles Komanoff, Carbon Tax Center 1. California carbon pricing is off to a fine start. While CTC would have preferred California price its carbon pollution directly with a carbon tax, we’re glad to see Mildenberger & Stokes report that the state’s carbon emissions have fallen more than 8 percent since cap-and-trade started up. That decline exceeds by at least half the 5.4 percent drop for the U.S. as a whole in 2013-2019 (calculated from national emissions data in the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2020), even as California’s economy was booming relative to the rest of the country. It’s regrettable that industry hardball watered down the program. But the authors present no evidence that emission reductions from unspecified “new regulations on California’s fossil fuels industry” would have surpassed those from carbon pricing. (The ProPublica story they linked to is silent on that score.) We’ve studied and applauded the state’s clean electricity standards and aggressive energy efficiency for more than four decades. M+S even cited our 2019 report documenting and quantifying these policies’ accomplishments, California Stars: Lighting the Way to a Clean Energy Future, shown at left. (They linked to it at “regulations,” in the last paragraph.) But much of energy demand and the resultant use of fossil fuels falls into huge pockets that even the best-crafted standards can’t touch, as we’ve discussed many times, at length (e.g., here and here). Unlike M+S, we don’t shy from touting the synergies between carbon pricing and energy standards. And there’s this benefit, too: Carbon pricing has already narrowed California’s “environmental justice gap,” as we documented in a new post earlier this week. |

| 2. Carbon pricing enrages right-wing populists.

California is one of only twelve U.S. states to have adopted any carbon price — the idea has simply proven difficult to enact. When Oregon attempted to vote on a carbon pricing bill in 2019, Republican legislators fled the state and hid in Idaho to prevent the quorum necessary to pass the law. And this isn’t just happening in the United States — the policy is politically unpopular around the world. When Australia passed a modest carbon tax in 2011, things got ugly quickly: right-wing radio hosts hurled misogynistic invectives against Prime Minister Julia Gillard; angry protesters descended on the parliament building in Canberra; and climate-denying opposition leader Tony Abbott crisscrossed the country, accusing the government of “economic vandalism.” When he took office three years later, Abbott quickly repealed the policy. In France a proposed carbon tax fueled the country’s yellow vest movement, triggering the worst domestic riots since 1968. The proposal was soon abandoned. |

2. Win over populists with wealth taxes.

As M+S surely know, the U.S. right is in open revolt against all climate action (even light-bulb efficiency standards!), not just carbon pricing. Ditto Australia. France’s “yellow vesters” weren’t protesting climate action, they were rising up against the yawning gap separating them from the super-rich, a gap that President Macron cruelly widened when he dialed back wealth taxes just before he pushed through a modest carbon levy that exempted aviation fuel. (See Christopher Ketcham’s vivid, on-the-ground reporting for Harper’s on the gilet jaunes, which we summarized last year.) The climate movement can harness the growing fury at the ever-expanding wealth gap with a program to tax both extreme wealth *and* carbon emissions and invest the proceeds into the Green New Deal, as we’ve written here. |

| 3. “Carbon pricing lets markets do the job.”

Part of [carbon pricing’s] enduring appeal is that it provides an elegant response to a complex problem. Carbon pollution is everywhere. So, economists argue, increase the cost of releasing it into the atmosphere, and let markets take care of the rest. [emphasis added] |

3. Repeat: carbon pricing is not a market measure.

Taxing carbon emissions has nothing to do with “markets” and everything to do with fixing the enormous market failure that allows fossil fuel companies and monster-truck drivers and frequent flyers pay zero for climate pollution. Please, can we all retire the “lets markets do the job” nonsense? |

| 4. Good on paper, poor in practice.

As climate change research grew more prominent in the 1980s, economists described pollution as a “negative externality” — polluters kept the profits from selling fossil fuels while society at large picked up the tab for the harm they caused. (emphasis added) If problems such as acid rain were “market failures,” then pricing forced polluters to “internalize” the costs. Anyone who released carbon pollution into the atmosphere would have to pay for the harm they caused. Policymakers have consistently pushed this idea at every level since the 1990s. And many economists remain attached to it: over 3,500 U.S. economists, including twenty-seven Nobel laureates, have signed a letter supporting carbon pricing… The idea developed into two main forms: a carbon tax and cap and trade. Carbon taxes impose a price on every unit of carbon pollution released. Cap and trade — also called emissions trading — limits the quantity of carbon pollution that can be released, with polluters trading permits to cover their emissions. Both methods promise the same theoretical result: a reduction in pollution. Like the roots of a tree branching out in search of water, a carbon price would find carbon wherever it was released. Goods made with fossil fuels would rise in cost. In response, people would make a million tiny decisions to get off carbon: buying the electric-powered lawn mower rather than the gas guzzler, jumping on a bicycle for the last mile rather than calling an Uber, switching to an induction stovetop and ditching the fossil gas. And it wouldn’t just be the public changing its ways; industries would also find places to cut back on carbon as their cost of doing business rose. Policymakers dreamed of sending these signals out across the economy to coordinate distant actors wherever the messages found them. The government could not possibly regulate all the myriad ways that carbon was emitted, but the power of the market could solve the problem — at least in theory. The problem with carbon pricing is not the idea on paper—it is its application in practice. According to economists, an effective carbon price must be high enough to make polluters pay for the externalities they generate. It must also cover all economy-wide sources of carbon pollution. |

4. Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

First, a shoutout to Mildenberger & Stokes for elegantly articulating the rationale for carbon pricing in their third paragraph at left (“Like the roots of a tree branching out in search of water …”). Bravo! Nevertheless, their formulation betrays a significant fallacy: The vast externalities from burning fossil fuels aren’t pocketed by the companies that extract and sell them, despite what M+S imply (“polluters kept the profits from selling fossil fuels”). Rather, so long as there’s a modicum of competition — as there is in the oil business — the monetary difference between the market price and the true social cost accrues to consumers. Absent carbon pricing, everyone who flips a switch, operates a vehicle or buys a manufactured product pays less than full price for the fossil fuels that enable the activity. Worldwide, the richest 1% of consumers cause double the carbon emissions of the poorest 50%, notes Oxfam in new research reported by The Guardian. In other words, the lion’s share of the multi-trillion dollar fossil fuels externality is pocketed by the global rich. The class disparity in U.S. emissions, though rising, is less stark, but here too, an outsize share of the carbon subsidy accrues to those who drive the oversized vehicles, jet around the globe, heat and cool their multiple dwellings, and so forth. If any fact deserves to be “centered” in progressive discourse about climate change and carbon pricing, it’s this one. Lately, though, the idea of human participation in fossil fuel use has been discarded. Current dogma pins all climate responsibility on the fossil fuel industry, even though the industry’s lifeblood is the gas pump and the light switch. The fossil fuel purveyors have plenty to account for. But centering them in policy seems to have lulled Mildenberger & Stokes into a binary view of carbon pricing, e.g., “an effective carbon price must be high enough to make polluters pay for the externalities they generate.” Actually, no. Any carbon price will set off a cascade of actions (as captured in that marvelous M+S third paragraph) causing cuts in carbon emissions. The higher the price, the greater the cascade. There is no single carbon price threshold or tipping point. The task before us is to win the highest carbon prices possible. |

| 5. Anyway, carbon prices are too low.

Carbon prices now exist in 46 countries, covering about 22 percent of the carbon pollution that humans release each year. But these policies are riddled with loopholes… Big carbon polluters — fossil fuel companies, electric utilities, automakers, petrochemical companies, and other heavy industries — have used their structural power to receive policy exemptions, handcuffing the invisible hand of carbon pricing. The result is that carbon pricing passes in the places that already have little pollution. For example, all U.S. states with [some] carbon pricing already had below average per capita energy-related carbon pollution in 2006, before these policies came into effect… Even when prices do exist, they are quite low. According to the World Bank, countries need policies between $40 to $80 per tonne to meet the Paris Agreement targets. Yet half of the world’s carbon prices are less than $10 per tonne, while only five countries — Sweden, Norway, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and France — are in the target range. Even the prices in these countries are probably too low. Estimates for the social cost of carbon — a measure of the societal harm carbon pollution causes—range from a couple dozen to several hundred dollars per tonne of CO2. University of California San Diego climate scientist Kate Ricke and colleagues estimate this social cost could be a staggering $417 per tonne. No carbon price in the world comes close to that number. |

5. The stall in carbon prices isn’t immutable.

It’s true that carbon pricing has stalled throughout the world. Too few countries have it, too few sectors are covered, and prices are far too low. This wasn’t pre-ordained. A promising moment for carbon pricing in 2008, sparked by British Columbia’s successful carbon tax launch, was snuffed out when the Great Recession unleashed a storm of right-wing nationalism. A second window — the 2014 U.S.-China bilateral agreement and the ensuing 2015 Paris climate accord — slammed shut a year later when Trump took power in Washington. We don’t wave away these facts, and we acknowledge how easily carbon pricing becomes kindling for climate resistance. This knowledge informed our decision to refrain from protesting the downplaying of carbon pricing in the Democratic Party’s 2020 platform. Likewise our decision in late 2019 to expand CTC’s mission to include taxing extreme wealth along with carbon emissions (see Point 2). Nevertheless, the fact that CO2 taxes of four hundred dollars a ton aren’t on the horizon doesn’t invalidate the ability of robust carbon taxes to propel large-scale reductions in emissions (see Point 6). We don’t have to “center” carbon taxing in climate policy, it just needs to be in the mix. And by making the carbon tax income-progressive, we can ensure that the mix is progressive as well. |

| 6. Carbon pricing won’t deliver the goods anyway.

In Norway, which has one of the highest carbon prices in the world, emissions in the oil sector rose by 78 percent between 1990 and 2017. One reason emissions didn’t fall is because of a problem economists call “demand inelasticity”: if an economic activity is extremely profitable, or if there are no easy alternatives, people and companies may not demand less even as prices increase… The evidence is mixed, however, on whether carbon prices can drive innovation and provide more of these cheaper substitutes we need. In her study of the national U.S. cap-and-trade program for sulfur dioxide, Margaret Taylor found that innovation actually declined after the system went into effect. As Tobias Schmidt has shown, cap-and-trade systems tend to produce incremental improvements in polluting technologies rather than driving new, clean alternatives. Other research suggests limited innovation. In their study of the EU’s carbon market, economists Raphael Calel and Antoine Dechezleprêtre estimate that patenting increased by 9 percent for regulated firms. However, given how few companies fell under the carbon price, overall low carbon technology patenting increased by less than 1 percent. Carbon price-induced patenting in the UK may have been considerably higher. Still, we lack strong evidence that carbon pricing has rapidly induced the innovation we need in new, cleaner technologies. By focusing on the low-hanging fruit—the “cheapest” ways to cut carbon pollution —we fail to build the ladder necessary to curb the more difficult emissions to reduce. And that shouldn’t surprise us. Consider this scenario: if the United States managed to implement a $50 per tonne carbon price, gasoline prices would increase by $0.44 per gallon. That means Americans’ monthly driving costs would increase by about $25, enough to put a dent in many families’ budgets. Some people might drive a bit less; a few might set up a carpool. But corporations will not innovate new technology because of minor tweaks in the price of energy. The prices of oil already fluctuate greatly year to year, and that hasn’t exactly produced the climate technology we need. |

6. Really? Look again.

Norway’s oil and gas extraction sector makes for a strange anti-pricing example, insofar as the sector’s carbon emissions have risen no faster than its growth in output (see calculations at end of section). Moreover, because Norway’s carbon tax hasn’t changed since the early 1990’s, it wouldn’t be expected to be driving cuts in emissions today. What the tax may have done is contribute to Norway’s oil and gas sector’s superior emissions intensity, nearly 60 percent less than the world average, according to research by Denis Hoffman, a chemical engineer working in Canada’s petrochemical industry, resulting partly from removing CO2 from natural gas and injecting it into undersea caverns — precisely the kind of innovation that M+S insist isn’t driven by carbon prices. The deeper truth is that while alternatives to buying and burning fuels may be easy or hard, depending on circumstance, they are almost always more available than most folks imagine or than M+S imply. Our own statistical analysis of U.S. gasoline usage since 1960 points to a price-elasticity of around (minus) 0.35, which translates to at least a 20 percent reduction in use from doubling the price. How would the reduction happen? Through daily behavior changes (trip-chaining, choosing closer destinations, more walk-bike-bus-train, less lead-footed driving) and, over time, changes in capital stocks (fewer guzzlers, more investment in and purchase of EV’s, greater infill development, and so forth). If we don’t see much give in gas use due to price swings, it’s because of the swings themselves. A carbon tax with a highly transparent annual ramp-up in the tax level would have less noise and more signal, spurring greater reductions. Our Norway calculations, unpacked: Per BP, Norway extracted 0.91 exajoules of fossil gas in 1990 along with 1,716,000 bbl/day of crude oil in 1990, and 4.12 EJ of gas in 2019 and 1,731,000 bbl/day of oil in 2019. Using 1 Btu = 1055 J and ascribing 5.8 million Btu to each barrel of crude oil, we have 1990 extraction of 0.863 quadrillion Btu’s (“Q”) of gas and 3.633 Q of oil totaling 4.496 Q, and, for 2019, 3.905 Q of gas and 3.665 Q of oil totaling 7.570 Q. The 1990-2019 increase in quads is 68.4 percent. We thank Prof. Mildenberger for updating his emissions figure to a 70 percent rise to 2019 and for clarifying that the figure covers oil and gas extraction. |

| 7. The emission reductions are too small.

If it hasn’t driven the necessary innovation, perhaps carbon pricing has delivered emission cuts? One model suggests Norway’s carbon tax reduced carbon pollution by about 2 percent in its first decade. Similarly the EU cap-and-trade system likely reduced emissions by about 4 percent between 2008 and 2016. In British Columbia, Canada, the carbon tax may have been more successful, reducing emissions by 5–15 percent between 2008 and 2015. But these reductions, while laudable, are nothing compared to what needs to be done — we need annual cuts of almost 8 percent a year until 2030 to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Evidence suggests carbon pricing won’t drive emissions reductions quickly enough. It is like bringing a stick to a knife fight. The policy might help for a little while, but it’s unlikely to secure a victory without other weapons to attack the problem. Economists have tried to sharpen the stick, pushing for better policy design, higher prices, and broader coverage. But their efforts have largely failed. |

7. Solid evidence, wrong conclusion.

The percentage figures from M+S at left seem right to us, especially for British Columbia, which we examined in depth in 2015, finding that per-capita emissions there fell 3-4 times faster than in non-taxing Canadian provinces during the first five years of BC’s carbon tax. That tax started in 2008 at $10 per ton of CO2 and topped out in 2012 at $30 — close to the limit of what a lone province or state can bear without huge gaming or leakage. If a $30 tax can cut emissions by 5-15 percent, imagine what triple-digit carbon taxes could accomplish. Rather than demonstrating that carbon pricing can’t drive emissions reductions quickly, BC’s success points to robustly rising carbon taxes’ vast potential. Mildenberger & Stokes are absolutely right that carbon pricing needs complementary policies. Few proponents of carbon pricing disagree. Economists haven’t failed, it’s the political system that hasn’t delivered. Criticism by climate hawks like M+S isn’t helping. |

| 8. Carbon dividends: just another try.

Carbon pricing … makes it easy for fossil fuel companies to rally opposition. Presenting themselves as champions of the little guy, these companies highlight how the policy would increase gasoline and electricity costs for the public. Polluters have even helped school boards and local governments estimate impacts from a carbon tax on their budgets. It’s not difficult to draw attention to these costs when everywhere we drive, giant signs declare the price of gasoline. If that number rises, people notice. There are no roadside signs displaying the devastating costs of climate change: wildfires, stronger hurricanes, rising sea levels, and new infectious diseases like COVID-19. What if we could make the benefits of carbon pricing more visible? This is the logic behind the price-and-dividend approach. Canada and Switzerland are the only two countries that have adopted this policy, though it is also part of proposed legislation in Congress. Like traditional cap and trade, this policy would cap emissions and require that companies buy pollution permits. Then U.S. residents with Social Security numbers would receive money back from the program, gathered from polluting firms. According to political scientist Theda Skocpol, a dividend would give the public a tangible benefit to organize around, thus contesting the power that entrenched polluters have over U.S. policymaking. Give the public a green check every month, the thinking goes, and it might just embrace climate policies. This is especially true for low-income households. Recent models by economists Anders Fremstad and Mark Paul show that a U.S. carbon tax, without compensation, would impose the greatest burdens on low-income households. A dividend could be designed to disproportionately return revenues to poor households. Carbon price and dividend gives greater attention to the politics of climate policy than earlier approaches, but it still struggles to make the benefits more salient than the costs. In the two countries with a price and dividend, the benefits are buried in income tax or health insurance forms. In our own research, we find these policies do not substantively increase public support for climate policy. This shouldn’t surprise us. Dividends are, at best, a band-aid solution to carbon pricing’s political woes. They create a debate over whether people want a check to cover their increased energy costs. Yes, some would rather have the check, but most would still prefer cheap energy. |

8. Do M+S know the policy they’re critiquing?

We’ve already noted (in Point 5) how easily carbon pricing is made a flash point. And we appreciate the authors’ relative openness to the “dividend” approach for distributing the revenues from carbon pricing. Alas, their treatment is muddled. We’ve rarely if ever seen reference to “price-and-dividend.” Rather, the guiding idea, popularized since 2009 by Citizens Climate Lobby as “fee and dividend,” is a straight-up levy (which CCL labels a fee) on the carbon content of fossil fuels, with the proceeds distributed to U.S. households in equal amounts (“dividends” or “green checks”). M+S aptly write, “Give the public a green check every month, the thinking goes, and it might just embrace climate policies.” Not just that, increase the size of the green check each year, and the public will buy in further. The expanding check could give lawmakers cover to ramp up the carbon tax rate, allowing it to start gradually at just $15 or $20 per ton but reach triple digits — a level that every economic model predicts will set off big (30-40 percent) emission reductions within a half-dozen years. And the promise of the ramp-up will spur households, planners and entrepreneurs to raise their decarbonization sights, unleashing waves of products and actions — infill development, higher product efficiencies, zero-energy buildings — locking in even larger cuts in fossil fuel use. Contrary to M+S, there’s no need to tailor carbon dividends to benefit poorer households; the policy’s very design does that automatically, by virtue of the pronounced tendency of poorer families to spend less on energy and fuels and richer families to spend more. We’ve lost track of the number of studies documenting that fee-and-dividend would be income-progressive in the aggregate, with few actual households losing ground. Again contrary to the authors, neither Canada nor Switzerland nor any other country has a carbon price with dividend. And why the straw man of burying the green check in other pots of money, when electronic benefit transfers could keep the dividend separate and make it manifest? Last, why the defeatism that most Americans would take cheap energy over the dividend check especially when most households’ green checks would outpace their higher energy expenses? (More on that score here.) And we ask Mildenberger and Stokes to bear in mind: the longer we keep energy cheap, the more time it will take to phase out fossil fuels and the greater the climate damage while we’re doing it. |

This takes us two-thirds of the way through the Mildenberger-Stokes article. The remainder mostly treads the same territory with the same strawmen: The gusher of renewables we need “cannot be achieved through carbon pricing alone.” “The objective should not be getting ‘the prices right.’” “Economists and climate policymakers must ask themselves: is insistence on theoretical efficiency more important than delivering climate stability?”

What are they talking about? Who are they talking to? Maybe because I’m not in academia, I don’t know a soul whose ardor for a carbon tax is driven by its theoretical efficiency. We want to tax carbon emissions because we believe doing so can deliver huge emission reductions fast — and equitably.

Where we do agree is in “breaking fossil fuel companies’ stranglehold on our political system.” And we appreciate the Mildenberger-Stokes argument that “large-scale industrial policy” including establishing and meeting clean energy targets, is the way to do that. That’s the Green New Deal, which CTC has backed from the git-go. But getting the GND rolling to the point where it muscles in on the fossil fuel companies won’t happen overnight — same as carbon pricing.

That carbon pricing doesn’t have the visceral appeal of a program centered on standards, investment and justice doesn’t warrant throwing it overboard. The carbon tax silver bullet may be a dead letter, but carbon taxing needs to live on. Even with millions of us in the streets and majorities in Congress, the Green New Deal will be a huge mountain to climb. Without pricing the climate damage from fossil fuels, getting to the net-zero mountaintop will take an awful lot longer.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- …

- 170

- Next Page »