Mary Annaïse Heglar, 2020: The Year of the Converging Crises, Rolling Stone, Oct 4.

Environmental Justice, Borne Aloft by Carbon Pricing

Note: A new (March 2021) CTC page, Carbon Pricing and Environmental Justice, summarizes this post and its Dec. 2020 follow-on, Dogmatism on Carbon Pricing Mustn’t Derail Climate Progress, and embeds them in a larger narrative about the environmental justice movement’s increasing turn against carbon pricing. See also CTC’s page, Progressives and Carbon Pricing.

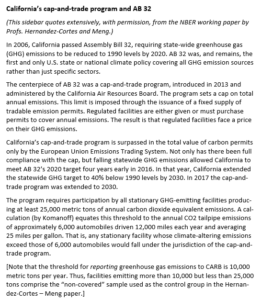

Could a new paper by two economists at the University of California at Santa Barbara upend the belief that carbon pricing cannot further environmental justice?

Drawing on millions of simulations of pollution trails from industrial smokestacks across California, UCSB PhD candidate Danae Hernandez-Cortes and Associate Prof. Kyle C. Meng have amassed convincing evidence that the state’s carbon cap-and-trade program has lessened the disproportionate dumping of pollution on disadvantaged communities.

So ingrained is this inequity that a decade ago, ground-level concentrations of pathogenic carbon “co-pollutants” — toxic particles and gaseous oxides — emanating from those smokestacks were three to four times higher in disadvantaged communities than elsewhere, according to the UCSB analysis.

So ingrained is this inequity that a decade ago, ground-level concentrations of pathogenic carbon “co-pollutants” — toxic particles and gaseous oxides — emanating from those smokestacks were three to four times higher in disadvantaged communities than elsewhere, according to the UCSB analysis.

The persistence of this and other stark instances of environmental injustice has nourished a conviction among many climate advocates that carbon pricing, whether rendered indirectly via emission permits or directly through carbon taxes, cannot mitigate pollution disparities affecting historically-burdened environmental-justice communities. As this belief has proliferated, some advocates have turned against carbon pricing measures as a way to reduce fossil fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions.

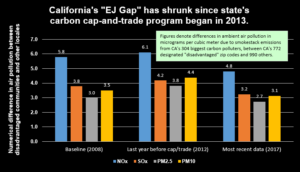

Now comes the UCSB economists’ finding that during the first five years of California’s carbon cap-and-trade program, what they call the state’s “EJ (environmental justice) gap” shrank considerably. From 2012 to 2017, the pollution disparity between disadvantaged and other communities fell an estimated 30 percent for particulates, 21 percent for nitrogen oxides and 24 percent for sulfur oxides.

“Disadvantaged community” is a legally defined term in California. It is measured with CalEnviroScreen, a multi-dimensional scoring system based on socioeconomic and other demographic indicators developed and maintained by the California Environmental Protection Agency.

Importantly, Hernandez-Cortes and Meng computed these shrinkages relative to a control group: industrial facilities whose smaller sizes exempted them from the cap-and-trade program. In this way, the researchers were able to conclude that “while the EJ gap was widening prior to 2013,” when cap-and-trade began, “it has since fallen by 21-30% across pollutants due to the policy” (emphasis added).

Scope of the UCSB paper

Hernandez-Cortes and Meng posted their paper, “Do Environmental Market Cause Environmental Injustice? Evidence from California’s Carbon Market,” in May on the web site of the prestigious National Bureau of Economic Research as a working paper — a preliminary form intended to make cutting-edge research available ahead of final publication. (Although the NBER posting is behind a paywall, it is available gratis at Ms. Hernandez-Cortes’ and Prof. Meng’s web sites, here and here.)

Because the EJ gap worsened considerably from 2008 to 2012, the post-2012 narrowing of the gap that the authors ascribe to the cap-and-trade program has only yielded a modest net improvement from the 2008 status quo. Nevertheless, the paper’s linkage of the 2012-2017 shrinkage of the EJ gap in California to a statewide program pricing carbon emissions is an apparent first.

Surprisingly, the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng paper has not attracted notice among climate advocates or researchers. It is not a casual read. It employs the techniques, and language, of mathematical modeling and statistics. That, along with its reliance on a “difference-in-difference research design” to sift the impacts of the cap-and-trade program from other ongoing phenomena, made it impracticable for the authors to express some of their findings as simple averages.

Moreover, the sheer size of their research sample — more than 300 power generators, refineries, cement plants, incinerators and factories that are California’s largest “stationary” carbon emitters — prevented the authors from tracing the specific pathways by which the cap-and-trade program elicited changes in individual plant designs and operations that brought about the emission reductions.

Nevertheless, their findings are unequivocal: the gaps in pollution burdens inflicted upon EJ communities vis-a-vis other locales narrowed conclusively — “statistically significantly” in academic parlance — for all four examined pollutants. The stigma against carbon-pricing policies as tools of environmental injustice is ripe for re-examination.

Breaking the mold

Emissions pricing has never gained much of a foothold among environmental justice campaigners. While mainstream economists traditionally view pricing of pollution as a necessary and benign market corrective, many activists recoil from its implicit acquiescence to capitalist means of exchange. To some, proposals to commodify pollution may serve as an unwelcome reminder of the central role of stolen labor and stolen land in the historical amassing of wealth by white planters and merchants. Emissions pricing can also appear antithetical to the Indigenous ethos that to monetize Nature is to desecrate it.

Added to this are the scars visited by an earlier California experiment with cap-and-trade — the RECLAIM (Regional Clean Air Incentives Market) program aimed at cutting emissions of smog-causing nitrogen oxides. By some accounts, the program’s softening of emission caps following the Enron-instigated power shortages in 2000-2001 greenlighted Chevron Corp. to bulk up on emission permits and expand operations at its sprawling Richmond petroleum refinery north of San Francisco rather than invest in costlier clean-up technology. The resulting concentration of pollutants in surrounding Black and brown neighborhoods erupted into a cause célèbre of environmental injustice, particularly in 2012 when a distillation unit at the refinery exploded, inundating fence-line neighborhoods in noxious plumes and reportedly sending 15,000 area residents to hospitals.

Initially, EJ antipathy to emissions pricing focused on cap-and-trade systems, not only because of the Chevron disaster but also because “pollution markets” were enabling blatant Wall Street profiteering. Moreover, early emissions trading schemes were riven by “offsets” that let polluters substitute offshore cuts for local action. Of late, distrust of pollution pricing has come to afflict even the straightforward taxing of carbon emissions.

“Carbon taxes will always be low, will always be evaded, do not cut pollution to the degree needed, and are greenwash.” So declared Carbon Pricing: A Critical Perspective for Community Resistance, a 2017 manifesto of the Indigenous Environmental Network and the Environmental Justice Alliance. A year later, as retiring California Governor Jerry Brown was convening a blue-chip “Global Climate Action Summit” in San Francisco, Indigenous and EJ demonstrators protesting Brown’s refusal to rein in petroleum fracking marched under a banner proclaiming that “Carbon pricing is colonialism.”

These harsh expressions could be viewed as an outgrowth of the failure of laissez-faire capitalism to contain carbon pollution, or, at a minimum, to alleviate its inequitable burdens on disadvantaged communities and households. Some of the stiffening line against carbon pricing may also be traced to the general radicalization of resistance movements during the Trump presidency, which has seen communities of color increasingly besieged by environmental assaults, systemic economic inequality, violent policing and Covid-19.

These harsh expressions could be viewed as an outgrowth of the failure of laissez-faire capitalism to contain carbon pollution, or, at a minimum, to alleviate its inequitable burdens on disadvantaged communities and households. Some of the stiffening line against carbon pricing may also be traced to the general radicalization of resistance movements during the Trump presidency, which has seen communities of color increasingly besieged by environmental assaults, systemic economic inequality, violent policing and Covid-19.

Concurrently, antipathy to carbon pricing was gaining further traction from an emerging body of research into the incidence of pollution from California’s carbon cap-and-trade law known as AB 32.

In 2015, a team of academics led by Prof. Lara Cushing, a well-known health-sciences scholar formerly at San Francisco State University and U-C Berkeley who is now at UCLA, began posting findings from an ambitious research project on AB 32. Their investigations culminated in a widely cited paper, Carbon trading, co-pollutants, and environmental equity: Evidence from California’s cap-and-trade program (2011–2015), which was published in the journal PLOS Medicine in 2018.

The Cushing team concluded that a majority (52 percent) of California “regulated facilities” — essentially, the same 300 or more factories and power plants that Hernandez-Cortes and Meng would tackle in their paper — increased rather than curbed their emissions of greenhouse gases following implementation of the cap-and-trade program. Moreover, the resulting increases in co-pollutants were disproportionately concentrated in communities with “higher proportions of people of color and poor, less educated, and linguistically isolated residents,” according to the PLOS paper.

These findings left a strong imprint on discourse about carbon pricing and environmental justice. Indeed, Prof. Hernandez-Cortes of UCSB mentioned in an email that she and Prof. Meng launched their research project after reading the original Cushing et al. working paper in 2015. Because of the salience of the issue as well as the “natural experiment” afforded by California’s carbon cap-and-trade program — the world’s second largest, after the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) — the UCSB scholars devised a research methodology to build on the Cushing team’s work in three respects.

How the UCSB paper improves on the Cushing analysis of AB-32

First, Hernandez-Cortes and Meng established a control group of 440 lesser California emitters that were not regulated by the cap-and-trade program; this “difference-in-difference research design” enabled them to weed out macroeconomic and other factors to discern the cap-and-trade program’s specific effects on emissions from the 306 larger, “covered” facilities. (Strong increases in economic activity across the state — California’s economy grew more than 17 percent during the five-year 2010-2015 period covered in the Cushing paper — also made it valuable to include a control group.)

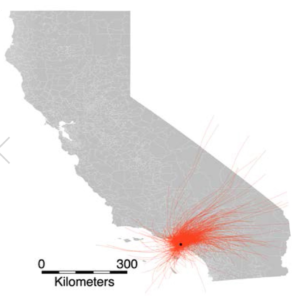

Second, Hernandez-Cortes and Meng sought to track where the carbon co-pollutants deposit after they have been emitted. The work by Cushing et al. implicitly assumed that only households within a 2.5-mile ring of a source are exposed to its emissions. Yet pollutants can and do travel scores and even hundreds of kilometers, especially from very large emitters, whose plumes typically exhaust through tall smokestacks and at high velocity.

Figure from Hernandez-Cortes & Meng NBER paper shows simulated particle trajectories from a polluting facility in Los Angeles in 2016. Used by permission.

To “explicitly model where pollution goes,” Hernandez-Cortes and Meng fed estimates of each facility’s emissions into an atmospheric transport model that traces pollutants’ paths once they have gone up and out the stack. “This was a highly computationally intensive process,” they noted in an email, “involving modeling over 11 million trajectories [and] taking over a week’s worth of high-performance cluster computing time.”

Third, whereas the Cushing findings emphasized whether each facility’s emissions rose or fell from 2012 to 2017 — an approach that flattened broad ranges of data into simple yes-or-no form — the UCSB economists calculated facilities’ emission quantities along with their deposition. This approach steered clear of potential distortions from assigning equal weight to the 300-plus facilities.

California’s Shrinking EJ Gap, Quantified

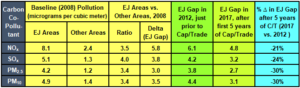

The table below summarizes the key findings of from the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng working paper.

The columns in yellow display ground-level concentrations of particulate and gaseous carbon co-pollutants from California’s 306 largest carbon emitters in 2008, expressed in the standard pollution-exposure metric of micrograms of pollution suspended in air. Perhaps even more striking than the “deltas” (numerical differences) between pollution concentrations in environmental justice vs. other communities are the ratios. Pollution levels in the EJ or disadvantaged communities were three to four times as high as in other areas. While these disparities were probably attenuated by pollution from mobile sources, which tend to be evenly distributed but were not included in the cap-and-trade program or the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng analysis, the differences are stark nonetheless.

All data are from Hernandez-Cortes & Meng NBER working paper cited in text, except Ratio column, which author calculated from first two columns. Those columns are from NBER paper Table S3 and indicate exposure levels due to cap-and-trade regulated facilities estimated across 722 (EJ) and 990 (Other) zip codes. Remaining figures were calculated from pre- and post-cap/trade slopes shown in NBER paper Table 1. Differences in last column from calculations with prior two columns are due to rounding.

The next column, in green, shows that by 2012 each pollutant’s “EJ gap” — the excess pollution deposited on disadvantaged communities relative to other California locales — had worsened even from their shocking 2008 base. Thereafter, however, coinciding with the onset of the cap-and-trade program, the gap narrowed significantly, as shown in the final two columns.

Consider the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng findings for PM2.5, in the third row of the table. PM2.5, designating fine particulate matter that lodges deep in the lungs and is implicated in illness and death from heart and lung diseases and strokes, is considered the most deadly air pollutant associated with industrial processes that emit climate-damaging carbon dioxide.

Over the four years starting in 2008, the UCSB economists found, the gap in levels of PM2.5 between EJ and other localities widened, from 3.0 micrograms per cubic meter to 3.8. However, beginning in 2013, the EJ gap for fine particulates contracted, falling to 2.7 µg/m3 in 2017 (the last year for which pollution data was available). That was 30 percent less than the 2012 gap of 3.8, and less than the baseline figure of 3.0 µg/m3 as well.

The state’s cap-and-trade program had a similarly beneficial impact on oxides of nitrogen, or NOx. This dangerous pollutant is the key constituent (along with volatile organic compounds) of the photochemical smog that since the late 1950s has infamously blanketed skies and seared eyes and lungs across much of California, with disadvantaged communities bearing more of the impact. NOx is also a precursor of “secondary” formation of deadly particulates. As shown in the table’s top row, from 2012 to 2017 the EJ gap for NOx shrank to 4.8 µg/m3, a level 21 percent below the 2012 figure.

Over the same five years, the environmental justice gap shrank by 24 percent for sulfur oxides and 30 percent for larger particulate matter, known as PM10, matching the decline in PM2.5.

Implications of California’s narrowed EJ gap

For all of its depth and rigor — or perhaps on account of it — the Hernandez-Cortes and Meng paper does not seek to explain why California’s cap-and-trade program should have shrunk the EJ gap in carbon co-pollution. The marked reductions they reported in their paper for all four pollutants are perhaps surprising, given that California’s cap-and-trade program was designed solely to engender the greatest pollution declines from emission sources that could most easily be abated at the lowest cost, without regard to location or incidence.

If, and only if, low-abatement-cost sources already are concentrated in EJ communities, would those populations be expected to enjoy above-average percentage rates of pollution reduction as a result of carbon pricing. Or so most economists reason. (Although AB 32 contains provisions for allocating a portion of the carbon permit revenues to disadvantaged communities, these would not be expected to induce facility owners and operators to concentrate emission reductions in those communities.)

For now, the UCSB economists’ finding that California’s comprehensive statewide cap-and-trade program has narrowed the EJ gap should be considered a fortuitous result. It should not be used to argue that carbon pricing policies, whether delivered via cap-and-trade or carbon taxes, will necessarily shrink EJ gaps elsewhere.

This caveat should not be taken too far, however. Even if disadvantaged communities shouldn’t expect carbon pricing to bestow disproportionate percentage reductions in emissions, pricing will still tend to deliver greater quantity reductions to those communities — and to any communities that suffer from excessive burdens of pollutants that the pricing measures address. This follows mathematically from the fact that a given percentage reduction applied to a larger amount translates to a greater quantity reduction than the same percentage reduction applied to a smaller amount.

A schematic example

To grasp this, consider Community A that suffers 100 daily doses of pollution while Community B suffers 50. A 20 percent reduction applied to both will cut the burden to A by 20 while cutting the burden to B by just 10. If the “before” EJ gap is expressed as a percent, with A suffering a 100 percent greater burden relative to B, then the percentage gap is unaffected by the across-the-board (20 percent) reduction, since the new burdens, which are 80 for A and 40 for B, still amount to a 100 percent gap. Yet it is also true that A’s reduction of 20 is twice B’s reduction of 10 — and that the EJ gap expressed as an amount has shrunk from 50 to 40.

This schematic suggests that community-neutral pricing policies stand to additionally benefit disadvantaged communities in health terms, even if the relative bias of disproportionate burdens on those communities remains untouched.

This is not to argue for community-neutral policies in the environmental realm or any other arena. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that such policies need not replicate the felicitous outcome thus far from California’s cap-and-trade program in order to benefit disadvantaged communities in an absolute sense, and, further, to confer larger benefits on them than on relatively privileged areas.

“The best thing that Joe Biden could do would be to speak in clear, exciting visionary terms about exactly what he plans to do to tackle the climate crisis, racial inequality and economic inequality.”

Sunrise Movement organizer Varshini Prakash, quoted by Michelle Goldberg in her NY Times column, How the Green New Deal Saved a Senator’s Career, Sept 4.

The magic of Joe Biden is that everything he does becomes the new reasonable. If he comes with an ambitious template to address climate change, all of a sudden, everyone is going to follow his lead.”

Entrepreneur and former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, quoted in Vox.com post by Zack Beauchamp, Andrew Yang said the smartest thing about Biden at the DNC, Aug. 20.

The depravity knows no bounds. Methane doesn’t linger for centuries like CO2, but over the near term, it’s a far more potent climate change forcer. What sickness leads people to scoff at urgent warnings from expert bodies? What cowardice prompts GOP officials to abet this evil?”

Sierra Club president emeritus Dave Scott, tweeting in response to a report in the New York Times that the Trump administration is making good on its threat to eliminate Obama-era rules limiting emissions of methane from leaks and flares in U.S. oil and gas wells (August 10).

We can have carbon border adjustments without being complicit in colonialism

This guest post is by Daniel Ambrosio, a development finance professional working in New York.

The European Union’s massive new economic recovery plan “is notable,” says Harrisburg University engineering professor Arvind Ravikumar, “for its focus on climate action, sustainable investments, and a just transition fund.” Writing in MIT Technology Review, Ravikumar applauds the EU’s €1.8 trillion ($2.1 billion) Covid stimulus package for putting climate policy front and center. Yet he takes aim at the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism that is a key component of the plan.

Monument to 17th Century British slave trader and member of Parliament Edward Colston in Bristol (U.K.) is toppled in June.

Ravikumar’s article, Carbon border taxes are unjust, calls Carbon Border Adjustments “colonial” and “a form of economic imperialism” because they reinforce the West’s historic irresponsibility in generating emissions both at home and abroad. In his view, carbon border taxes also fortify Western-based corporations’ ongoing, destructive investment in extractive fossil fuel infrastructure throughout the less-developed world.

It is true that by themselves Carbon Border Adjustments do not address these issues. But does that omission disqualify them? Must correcting historic inequities be a requirement for any and every aspect of climate policy?

Carbon Border Adjustments

A Carbon Border Adjustment is a tax on imports based on the carbon emissions of their production — more precisely, based on the difference between respective carbon tax rates in the importing country and the producing country. If an importing country is taxing its own carbon emissions at, say, $100 per ton of CO2 while the producing country’s tax is just $20, the importing country may impose a Carbon Border Adjustment of $80 on each ton of CO2 ascribed to manufacture of the imported product.

In effect, Border Adjustments supplement a local tax on carbon emissions “production” with a tax on local emissions “consumption” produced abroad. A properly designed (and WTO-compliant) border adjustment thus holds local and foreign producers to a common standard. As both Ravikumar and the EU note, this is necessary to prevent “leakage” of industrial emissions production to untaxed jurisdictions.

Leakage risks are not hypothetical. As Ravikumar notes, “globalization helped the developed world shift manufacturing and outsource its associated pollution burdens to China and other developing countries.” Systematic exemption from Western regulatory regimes for pollution, health and safety and social safety nets powerfully abetted concentration of carbon pollution in the developing world, with myriad local air and water pollution impacts. Yet Ravikumar’s article makes no mention of the possibility that developing countries might foster their own energy transition with carbon taxes, at which point EU border adjustments on imports from these countries would be moot.

A carbon tax on a marginal ton of CO2-equivalent emissions reflects historic untaxed emissions. In other words, because emissions have only just begun to be taxed, returning atmospheric concentrations to pre-industrial levels (or at least capping their rise, as is the EU’s aim, i.e., net carbon-neutral by 2050) requires a tax which internalizes not the damage of a ton of CO2 in isolation, but the damage of that additional ton in the specific context of atmospheric concentrations as they are and the distance needed to travel to meet targets.

Criticism of this approach is correct in that it is blind to 1) who caused the damage to this point, 2) how well situated an individual, firm or nation is to cope with the cost internalization, and 3) the degree of agency these individuals, firms and nations have over their emissions levels. However, the incidence of this taxation — who ultimately bears its burdens — is only one facet of how the costs are ultimately borne.

Disentangling Price Signals and Climate Justice

Many carbon tax proposals and implementations are committed to revenue neutrality. The intent is to price emissions and thus create an economy-wide impetus for behavioral and structural changes while holding average cost of living in place. And while revenue-neutrality does not directly address the international legacy emissions problem, it at least does not exacerbate it.

Global inequity can be addressed through use of carbon border revenues or separate climate reparations such as wealth transfers, technology transfers, concessional financing, and reduced trade barriers. Ravikumar notes, “The Green Climate Fund — established as part of the Paris [climate agreement] — is a good start, but it is not sufficient, nor has it been fully endowed.”

Revenues from carbon border adjustments could fill the funding gap. The broader point is that imposing carbon border adjustments does not preclude addressing international climate justice. Putting a price on carbon that limits regulatory arbitrage and thus discourages emissions leakage is the single most equitable way to distribute the price signals that drive low-carbon investment and behavior. It is also almost certainly a sine qua non to overcome trade-union and other worker-based opposition to carbon taxing in the U.S. and other industrial nations.

Ravikumar’s article advances its own intriguing proposals for climate equity:

Reforms to WTO rules should allow developing countries to grow a domestic green manufacturing sector without triggering a WTO dispute. Developed countries and global financial institutions should extend access to low-interest financing, as well as to technology transfer and bilateral trade and exchange programs that help build capacity for climate mitigation and adaptation in developing economies.

None of these is incompatible with a carbon taxing and border adjustment scheme. Nevertheless, given how repeatedly the article decries “colonialism,” it is worth nothing that each of Ravikumar’s proposals reflects a top-down approach likely to advantage firms with political clout, at least compared to the impartial approach of broad carbon pricing.

The article does bring to the surface a number of important considerations as the EU develops its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism through consultations. However, its animus toward Border Adjustments appears misplaced.

If the Democrats run the table in November

As in 2016, Democrats appear poised to capture the White House and perhaps the Senate while retaining the House. Let’s explore what a Democratic presidency and Congress might mean for climate policy and carbon taxing.

Caveats first. We offered a similarly rosy prediction in 2016, a month before Election Day. In a post on Oct. 9, The Political Meltdown That Could Save the Climate, we said that the “Access Hollywood” tapes were leading “shell-shocked Republicans to abandon the Trump ship.” Little did we know that the Trump campaign was already detonating a wave of counterattacks that would culminate in FBI director James Comey’s catastrophic Oct. 28 letter to Congress dredging up Hillary Clinton’s emails. Nor did we imagine that most swing-state voters who disliked both candidates would pivot sharply from Clinton, or that her seemingly impregnable lead was partly an artifact of pollsters’ under-representation of Trump’s top demographic, non-college white voters.

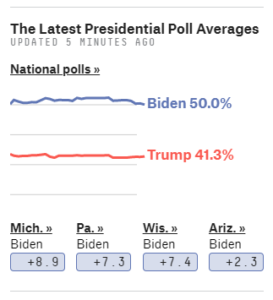

In mid-July, Biden was sitting on comfortable leads in the three Rust Belt states that swung the 2016 election to Trump, according to FiveThirtyEight.

Even more wild cards abound this time: possible election intimidation and interference, Covid-related voting reluctance, and of course Trump’s proven willingness to say and do almost anything to hold onto power. Plus, the election is still 16 weeks away — “an eternity in politics.” Nevertheless, Biden’s position today looks stronger than Clinton’s four years ago.

With Democrats rallying solidly around Biden, the trifecta of Covid, economic privation, and revulsion at white supremacy may be too much for the incumbent to overcome. At this writing (July 14), FivethirtyEight.com has Biden leading by at least 7 points in the three states that tipped the 2016 election to Trump. As for the Senate races, though polling is thinner, Democrats are being given the edge in a majority of the eleven most competitive races; they need only take five to gain the majority (four if Biden wins).

So let’s make the optimistic assumption that the party of climate denial, tax inequality and All Lives Matter is trounced this November. What’s in store for climate and carbon pricing?

Tackling Inequality and Climate Change

New York Times columnist David Leonhardt last week singled out the Democrats’ agenda’s “two defining features”:

The first is reducing inequality — through higher taxes on the rich, greater scrutiny of big companies, new efforts to reduce racial injustice and more investments and programs for the middle class and poor, including health care, education and paid leave. The second is acting on climate change. (From It’s 2022. What Does Life Look Like?, July 10; emphases added)

Those two elements overlap with the three building blocks we articulated for climate progress in our Dec. 2019 post, A New Synthesis: Carbon Taxing, Wealth Taxing & A Green New Deal.

Leonhardt contends that while “[Joe] Biden may not seem like a history-altering figure, certainly like less of one than Barack Obama did. . . he could wind up presiding over a larger scale of political change than Mr. Obama did, for reasons largely independent of the two men themselves.” One reason is that unlike the start of Obama’s presidency, which coincided with the onrush of the 2008 financial meltdown, “today, by contrast, progressives have spent years working through the details of plans on climate change, high-end tax increases, antitrust policy and more.”

“There is a whole vision that I think is ready,” says economist Heather Boushey, who runs the progressive-leaning Washington Center for Equitable Growth, and whom Leonhardt quotes. “And there is a lot more runway,” she told him, contrasting the ten or so months Biden’s team will have had to lay out their plans with the mere two months available to Obama.

The other factor militating for potentially sweeping legislative change under Biden, in Leonhardt’s view, is the vast scope of disruption in the past two decades. This period includes “the biggest two economic crises since the Great Depression, the worst pandemic in more than a century and the election of two presidents unlike any before them — and diametrically unlike each other.” He could also have mentioned the breadth and militancy of the resurgent U.S. left, which has served notice that it has no intention of letting up or bargaining down during a Biden presidency — a perspective that suffuses another, more visionary essay that the Times published alongside Leonhardt’s, The Left Is Remaking Politics, by Ohio State University law professor Amna A. Akbar.

Standards-Investment-Justice: an emerging Democratic Party alignment on climate

In late May, Vox climate writer David Roberts published At last, a climate policy platform that can unite the left, a monster (6,000-word) post drawing on his decade covering U.S. energy and climate policy and politics.

Roberts posits, and offers as his post’s subhead, that “the factions of the Democratic coalition have come into alignment on climate change.” “For the first time in memory,” he writes, “there’s a broad alignment forming around a climate policy platform that is both ambitious enough to address the problem and politically potent enough to unite all the left’s various interest groups.”

Roberts quotes Maggie Thomas, former campaign aide to Jay Inslee and Elizabeth Warren, now with the climate mobilization group Evergreen Action: “All of those people who ran for president … had a much more expanded vision on climate by the end of their campaigns than when they started,” and then offers sections entitled Net-zero emissions by 2050 is the new baseline, Republicans aren’t going to help, and Carbon pricing has been dethroned (we’ll have more on that in a bit), before unveiling his synopsis of this emerging Democratic climate alignment:

- Standards: “[E]lectricity, cars, and buildings together … make up close to two-thirds of US emissions. The core of any aggressive 10-year mobilization on climate must be to target them, not sideways through a carbon price, but directly, through sector-specific performance standards and incentives, to drive out the carbon as quickly as possible.” Details vary among various (former) candidates’ platforms and advocacy groups’ programs, Roberts, notes, “but there is a strong common core: performance standards and incentives for the three biggest emitting sectors, aimed at making rapid, substantial progress on emissions in the next 10 years [with] the ultimate vision a carbon-free electricity sector powering an electrified, emission-free vehicle fleet and building stock.”

- Investment: The idea of “large-scale public investment,” says Roberts, “is not new, but something about the moment — the rising danger of climate change, the growing influence of Sanders-style democratic socialism, the pent-up public need after decades of austerity politics — made it resonate.” “The investment ideas cover a wide range, e.g., rural electrification, universal broadband, long-distance electricity transmission, and electric vehicle charging infrastructure [though public transit goes unmentioned here], but the focus in all of them is supporting green industries, manufacturing, and research, and, above all, creating jobs.”

- Justice — “for unions, fossil fuel workers, and front-line communities,” per Roberts’ summary. “Putting justice first,” which the emergent alignment does, “represents the most notable shift in green thinking and strategy over the past decade,” in Roberts’ estimation. And I believe he’s right. Whereas “climate justice” has been construed primarily as remediation and protection for marginalized constituencies that are predominantly Indigenous or communities of color, it is now extended and broadened to encompass workers in obsolescent fossil-fuel industries, the regions burdened by energy extraction and processing, and under-employed people.

Is “Standards-Investment-Justice” reconcilable with CTC’s “Taxing Carbon and Wealth for a Green New Deal”?

While the Standards-Investment-Justice moniker is largely Roberts’ formulation, the idea it encapsulates has been in the air for a year or more and is now trending. It’s easy to see why. Performance standards are broadly accepted in the U.S., if not by Fox News mouthpieces then by an impressively broad spectrum from environmental groups to appliance manufacturers. (The standards rubric also includes state-level clean-electricity standards that many credit with priming the wind and solar power pumps for the past one or two decades.) Investment is newly resonant for the reasons Roberts notes, with credit also due Green New Deal proponents including the Sunrise Movement for their constant invocations of FDR’s presidency (minus the racist exclusions). Justice, a bedrock human ideal, here becomes a rubric to unite two factions that are vital yet have rarely been joined politically: the environmental justice left and the more traditional labor center.

“S-I-J” strikes us, then, as empowering and vital. But what about “P” for pricing — carbon pricing? Recall that Roberts dissed it, in the Carbon pricing has been dethroned section of his post. Here’s how he put it:

Carbon pricing — long treated as the sine qua non of serious climate policy — is no longer at the center of these discussions, or even particularly privileged in them. For one thing, there’s the political economy: Raising prices is unpopular, and raising prices enough, fast enough, to hit the 2050 [net-zero emissions] target will be an almost insuperable political challenge. Cap and trade is still in the reputational toilet. Carbon taxes never saw the bipartisan support their backers always promised. The politics of carbon pricing just don’t seem to be going anywhere.

Roberts is right on several counts: Carbon pricing is no longer centered in climate policy. Raising prices is politically difficult. Cap and trade is toxic. And carbon taxing has lacked bipartisan support since the 2009 Tea Party insurrection (the occasional Republican mild pats-on-the-back for token carbon taxes don’t really count).

But his insinuation that carbon pricing in isolation can’t get us to net-zero emissions by 2050 is a straw man; no carbon pricing advocate of any stature has posed it as a stand-alone measure for a long time. More importantly, the absence of bipartisan support shouldn’t disqualify carbon taxes from consideration by a Democratic White House and Congress, should that be the outcome of the November elections. With Democratic majorities, and assuming the newly Democratic Senate abolishes the filibuster, a meaningful carbon tax, e.g., one that begins at $15 or $20 per ton of CO2 and rises annually by $15 to reach $100 per ton within seven years, ought to be able to get through Congress and reach the White House.

Biden’s $2 Trillion Climate Plan

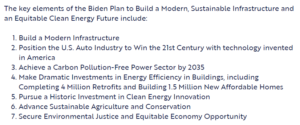

Yesterday, the Biden campaign released its climate plan. The Biden Plan To Build A Modern, Sustainable Infrastructure And An Equitable Clean Energy Future would invest $2 trillion over the next four years to build new infrastructure, boost clean energy, and repair and remediate communities historically damaged ecologically and socially by fossil fuel extraction and burning.

The Biden plan appears to embed carbon reduction in a broader framework of economic recovery, infrastructure revival, racial equity, and jobs — apt framing in light of the Depression that has enveloped the U.S. in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Trump administration’s largely business-as-usual stance, as well as the awakening of many Americans to the ongoing damage from persistent structural racism.

Release of the plan followed on the heels of the Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force’s policy recommendations on climate change issued last week (July 9), which in turn hewed fairly closely to the June recommendations of the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. The select committee’s “majority” report (from the Democratic conference), Solving the Climate Crisis: The Congressional Action Plan for a Clean Energy Economy and a Healthy and Just America, “calls on Congress to build a clean energy economy that values workers, centers environmental justice, and is prepared to meet the challenges of the climate crisis.”

Release of the plan followed on the heels of the Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force’s policy recommendations on climate change issued last week (July 9), which in turn hewed fairly closely to the June recommendations of the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. The select committee’s “majority” report (from the Democratic conference), Solving the Climate Crisis: The Congressional Action Plan for a Clean Energy Economy and a Healthy and Just America, “calls on Congress to build a clean energy economy that values workers, centers environmental justice, and is prepared to meet the challenges of the climate crisis.”

We’ve read the Biden Plan’s write-up of its seven key elements, shown above — U-C Santa Barbara poli sci professor and climate savant Leah Stokes has an excellent Twitter thread on it, by the way — and have seen nothing about, or even hinting at, carbon taxing or carbon pricing of any stripe. On the other hand, another part of the Biden Campaign’s climate page, Biden’s Year One Legislative Agenda on Climate Change, includes language suggesting support for pricing carbon emissions:

This enforcement mechanism [to achieve net-zero emissions no later than 2050] will be based on the principles that polluters must bear the full cost of the carbon pollution they are emitting and that our economy must achieve ambitious reductions in emissions economy-wide instead of having just a few sectors carry the burden of change. (emphasis added)

That said, sifting various iterations of the Biden campaign’s climate platform doesn’t feel particularly useful. Whatever climate legislation (and executive action) emerges from a Biden administration and Democratic Congress is likely to be determined more by the demands of the climate movement this year and next than by Biden campaign statement. The implication is that carbon tax advocates would do better educating fellow climate campaigners on the need for carbon taxing — and, of course, organizing for electoral change this summer and fall — than bemoaning the absence of carbon taxing from current climate discourse.

We give the last word to the Times’ David Leonhardt, whose July 10 column we drew on, above:

“If there is a single lesson of the current era of American politics, it’s that change can happen more quickly than we imagined.”

[The Democrats’] agenda is shaping up to have two defining features. The first is reducing inequality . . . The second is acting on climate change.”

NY Times columnist David Leonhardt, It’s 2022. What Does Life Look Like?, July 10.

New York Times Starts Embracing ‘Future without Cars’

I posted this on Streetsblog yesterday. It’s somewhat NYC-centric and doesn’t mention climate change, but it’s indicative of how fast opinion and, hence, policy can change, especially now, during the pandemic. — CK.

“Live long enough,” the saying goes, “and you’ll see everything.”

So it is. On Friday, we saw perhaps the first-ever NY Times link to “Banning Cars from Manhattan,” the seminal 1962 samizdat essay that suggested another urban world was possible. We also saw a 3,000-word essay revivify the truths in the classic 1980s underground sticker, “Ban cars from the city: They pollute, they kill people, they take up space.”

All this, and more, in a piece provocatively titled, “I’ve Seen a Future Without Cars, and It’s Amazing” by Times opinion columnist Farhad Manjoo — with a subtitle that dared to ask, “Why do American cities waste so much space on cars?”

To paraphrase jazz immortal Sun Ra, space is place for us urbanists. To me, what makes Manjoo’s essay so distinctive is its focus on the immense space cars and driving require. That, plus its conviction that New York and other cities can and must be transformed, now — during and post pandemic; plus that it appeared in the New York Times, automatically giving it currency and gravity.

Space — the word — appears 19 times in the essay. Its close cousin, land, shows up for 15. “If cars are our only option, how [after the pandemic] will we find space for all of them?,” Manjoo muses. Cities’ “worst mistake [was] giving up so much of their land to the automobile,” Manjoo declares:

Automobiles are not just dangerous and bad for the environment, they are also profoundly wasteful of the land around us: Cars take up way too much physical space to transport too few people. It’s geometry.

Cars wasting space is old hat to anyone who spends much time biking in New York City. And the hopeless geometry of cars in cities has been a thing on “Transit Twitter” for some time. But I’ll bet Manjoo’s message struck Gray Lady readers as fresh and new. Even if they’re now schooled in tailpipes and carbon and crashes, most “normies” probably haven’t thought that “as roads become freer of cars, they grow full of possibility.”

Manjoo is speaking to this car-cocooned majority, sagely anticipating their objections and trying to help them get over, with passages like this:

What’s that you say? There aren’t enough buses in your city to avoid overcrowding, and they’re too slow, anyway? Pedestrian space is already hard to find? Well, right. That’s car dependency.

Without cars, Manjoo explains, “Manhattan’s streets could give priority to more equitable and accessible ways of getting around.” Crucially, these better ways aren’t ride-hails or Teslas or self-driving cars. Indeed, one of the essay’s notable feature is its kiss-off to digerati fantasies of melding technology, automobiles and cities. (Manjoo, a former reporter, covered Silicon Valley.)

No faux disrupter, Manjoo is going sustainable and long, urging bike superhighways and bus rapid transit and congestion pricing and ample sidewalks — elements of a wholesale repurposing of the vast space taken up by moving cars, parked cars, cruising-for-parking cars, stuck-in-traffic cars, refuel stations and the like.

In Los Angeles, “land for parking exceeds the entire land area of Manhattan, enough space to house almost a million more people at Los Angeles’s prevailing density.” And just in Manhattan, “nearly 1,000 acres … is occupied by parking garages, gas stations, car washes, car dealerships and auto repair shops.” (Central Park covers 840 acres.)

“The amount of space devoted to cars in Manhattan is not just wasteful, but, in a deeper sense, unfair to the millions of New Yorkers who have no need for cars,” Manjoo writes, before teeing up this killer quote from urban planner Vishaan Chakrabarti: “It really does feel like there is a silent majority that doesn’t get any real say in how the public space is used.”

Chakrabarti, whose Practice for Architecture and Urbanism firm provided underpinning for Manjoo’s column, here joins the Regional Plan Association in demanding that politicians stop coddling the pro-car NIMBY’s who overpopulate city community planning boards and problematize virtually every measure that might take space from cars.

“Cars aren’t just greedy for physical space,” Manjoo writes, “they’re insatiable,” calling out the true meaning of induced demand: “an unwinnable cycle that ends with every inch of our cities paved over” (an outcome sadly familiar to aficionados of Streetsblog’s Parking Madness tournaments).

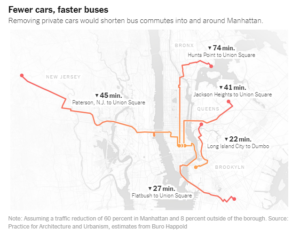

Shortening of commute times in map assume 60% reduction in traffic in Manhattan, with “ripple” reductions in neighboring areas.

“Cars make every other form of transportation a little bit terrible,” Manjoo adds, perhaps understating. “The absence of cars, then, exerts its own kind of magic — take private cars away, and every other way of getting around gets much better.” That goes for walking, biking, scootering, even taxis and Ubers, Manjoo notes, but, above all, for buses, as the graphic at right showing time savings from removing Manhattan car traffic makes clear.

I posted that graphic on Twitter in response to concerns that barring most private autos from Manhattan and upgrading bus service to BRT, as Manjoo suggests, “wouldn’t serve equity.”

“On what planet,” I asked, “is cutting super-double-digit minutes off bus commutes in/around NYC not a win for equity?”

Of course, a win for equity like humane and efficient buses is a poor stand-in for an across-the-board commitment to equity, as was pointed out in response.

“A true commitment to equity changes the power structure for making decisions,” added another commenter — and I fully agree.

But I don’t think it’s helpful to fault Manjoo’s article, or their vision, for failing to confront power structures that enforce economic inequality or white supremacy. Dismantling those structures is the paramount work of our time, in my view. And I want no part of any measures that would further entrench them. Yet making New York and other cities safe, sustainable and habitable for their hundred million or more inhabitants is also vital. I’ve seen nothing suggesting that aggressively reducing car dependence along the lines urged by Manjoo will either interfere with that work or worsen conditions for communities of color and other underserved constituencies.

The 2021 races for mayor, public advocate, comptroller and city council are fast approaching, and Manjoo has sent NYC livable-streets advocates a clear signal to elevate our game. The signoff from their column gets the last word (emphases added):

Many of the most intractable challenges faced by America’s urban centers stem from the same cause — a lack of accessible physical space. We live in a time of epidemic homelessness. There’s a national housing affordability crisis caused by an extreme shortage of places to live. And now there’s a contagion that thrives on indoor overcrowding. Given these threats, how can American cities continue to justify wasting such enormous tracts of land on death machines?

How, indeed?

if you’re distressed by the devastating costs of covid-19 wherever officials have dismissed and denied the science and public health warnings — wait til you see the vastly greater costs of the same officials’ same dismissal and denial of climate change.”

New Yorker staff writer Philip Gourevitch (@PGourevitch), on Twitter, July 2.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- …

- 170

- Next Page »