[NB: A longer version of this post was published on March 13, 2020 in Counterpunch.]

Prologue

Good lord, how do you schedule the spring ticket traps at the same time as you tell people to bike to work https://t.co/DCAIZDvnDc

— Good Idea Dave (@DaveCoIon) March 10, 2020

The tweets above, from a bicycle commuter and a local journalist, are New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio in a nutshell. Even as he was encouraging coronavirus-concerned commuters to cycle to work, he not only failed to carve out special lanes on streets and bridges, he also stood by while NYPD conducted its customary cyclist-summonsing traps as if nothing had changed.

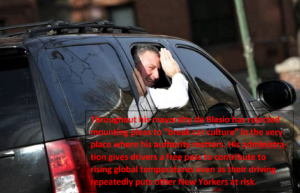

Ditto on the climate crisis. For two years running de Blasio has made a show of divesting from and suing fossil fuel companies, winning him the allegiance of the climate vanguard. Yet throughout his mayoralty he has doggedly rejected mounting pleas to “break car culture” in the very place where his authority matters. His administration consistently gives drivers a free pass to contribute to rising global temperatures even as their driving repeatedly puts other New Yorkers at risk.

I have a foot in both the climate camp and New York’s “livable-streets” camp. I’ve fought fossil fuel use for almost half a century and currently head the militant pro-climate Carbon Tax Center. Locally, I’ve been an architect of congestion pricing, a bicycling activist and a direct-action campaigner for pedestrians’ rights. The juxtaposition of de Blasio’s climate calls-to-arms with his pro-driving policies is head-spinning.

I have a foot in both the climate camp and New York’s “livable-streets” camp. I’ve fought fossil fuel use for almost half a century and currently head the militant pro-climate Carbon Tax Center. Locally, I’ve been an architect of congestion pricing, a bicycling activist and a direct-action campaigner for pedestrians’ rights. The juxtaposition of de Blasio’s climate calls-to-arms with his pro-driving policies is head-spinning.

Is it worth calling out a lame-duck mayor’s complicity in car culture? Yes. New York retains an outsize influence on urban policy and culture. Actions here to de-emphasize automobiles could reverberate globally and help shrink burgeoning transportation emissions. Moreover, de Blasio recently returned to the national stage, stumping for Bernie Sanders. Before his self-proclaimed myth as climate mayor goes national, we should scrutinize his record.

De Blasio is M.I.A. on breaking car culture

Public interest in transit and traffic in New York City blossomed over the past decade. Ideas and activism abound. De Blasio remains oblivious.

Take congestion pricing. For years the mayor’s answer to proposals to toll drivers entering Manhattan was ginned-up sob stories about having to pay $12 to drive to $500 doctor visits. He got on board only after his hand was forced by the governor.

Or “Fair Fares,” the progressive brainchild of having city government pick up half of the cost of poor families’ Metrocards. De Blasio brushed it off until City Council activists attained a veto-proof majority. When it passed, City Hall slow-rolled the implementation.

Busways? Transit buses have hemorrhaged ridership for years, largely because mounting car and truck traffic has brought them nearly to a standstill. After de Blasio agreed to let transportation officials pilot car restrictions on one crosstown route, speeds and usage shot up. Yet the mayor hasn’t committed to replicating it elsewhere.

The story repeats on almost every transportation front. The mayor stood by as Uber and other ride-hailing services muscled into the Manhattan taxi franchise, bankrupting thousands of cab drivers, worsening traffic and undermining mass transit. He let free-parking pleaders delay bicycle lanes even as biking fatalities hit a 20-year high. And de Blasio’s signature “Vision Zero” traffic-safety initiative is undermined daily by his denial of NYPD’s entrenched pro-driver bias. Police issued more summonses to bicycle riders than truck drivers last year. Unsurprisingly, pedestrian fatalities, many under the wheels of trucks, are on the rise.

The twin threads running through this account are passivity and fatalism. In de Blasio’s New York, everyone is a driver and every car and truck trip is sacrosanct.

Confronting Big Oil has delivered little

The mayor’s bold words on climate haven’t yielded much. On divestment, it took city officials two years simply to select advisers “to evaluate options and recommend actions.” The city’s lawsuit seeking to hold oil and gas companies liable for climate change harms was dismissed in federal district court, for pre-emption.

But a municipal climate strategy built on attacking Big Oil has a graver defect: Neither divestment nor litigation materially alters the systems of demand and supply that generate the carbon emissions that are wrecking the climate.

To be sure, divestment campaigns and demands to hold fossil fuel companies liable are contributing mightily to movement-building and elevating climate change politically. Because of these campaigns, climate advocacy has been surging, which promises big policy dividends down the road.

But it’s also true that even if fossil fuel stocks are dumped from city pension portfolios, every drop of drivers’ demand for fossil fuel will still be met at the gas pump.

From a carbon standpoint, divestment, litigation and general saber-rattling against Big Oil are essentially performative acts. Payoffs will take decades to appear. Yet de Blasio holds the reins over a multiplicity of policies that determine how much New Yorkers drive and, thus, how much gasoline they burn. He simply chooses not to wield them.

Why is “breaking car culture” anathema to de Blasio?

What accounts for de Blasio’s disinterest in reducing automobile use in New York City? For one thing, he appears genuinely terrified of yoking the NYPD to any action that might appear anti-car or anti-driver. But the roots of the mayor’s reticence lie deeper: De Blasio lives inside a windshield world.

Questioned not long ago about possibly converting “free” parking on residential streets to metered parking, de Blasio said:

“If we’re going to tell people they can’t park on their street, no, that does not ring true to me. If you go so far as telling people they can’t park on their street, no, I’m not there.”

Yet the idea put to the mayor wasn’t to ban street parking but to charge for it — which could make parking easier for most by inducing a fraction of residents to stop storing cars on the street.

The same reflexive identification with a traditional conception of driving underlies de Blasio’s gut-level resistance to nearly every proposal to alter the city’s streetscapes so New Yorkers can safely and easily get around without a car.

As one City Hall reporter put it, “De Blasio is a driver. He’s also a very affluent man who views himself as an average middle class guy. So he genuinely believes ‘Oh this [congestion pricing] is going to hurt lots of regular Joes’ without examining any data behind that belief.”

Yet congestion pricing alone will cut New York City’s CO2 pollution by nearly a million metric tons a year, an amount nearly triple the drop in New York’s car and truck emissions from 2005 to 2017 (which came about only because federal mileage standards — pre-Trump — made new cars less inefficient).

And those million tons are just congestion pricing’s down payment for climate. As I wrote two years ago, when the mayor was still badmouthing the idea:

Congestion charging’s true climate payoff is in the households, jobs, and activities that will locate or remain in the city, rather than fleeing to the new exurban ring or the Sunbelt, which have carbon footprints many times larger than New York’s.

Is climate posturing de Blasio’s way to avoid reckoning with NYC’s car culture?

Notably absent from the livable-streets movement are most self-described climate activists — groups like Bill McKibben’s 350.org or Food and Water Watch. This prompts the question: are plaudits from climate leaders letting the mayor deflect efforts to downscale the primacy of cars and make the streets not just safer but more sustainable?

Make no mistake: the climate vanguard’s embrace of the mayor is powerful. Just last month, McKibben posted on Twitter:

Remarkable: in his State of the City address, @NYCMayor Bill de Blasio just said NYC will never again approve new fossil fuel infrastructure. That is, the fossil fuel age is now officially in its twilight in the world's financial and diplomatic capital

— Bill McKibben (@billmckibben) February 6, 2020

Emphasis added: The fossil-fuel age is now officially in its twilight in the world’s financial and diplomatic capital.

To learn how the cyclist came to be crushed by the minivan, click on the link under “hellscape of cars and trucks” at left.

New Yorkers by the thousands have organized for years to win better subways, safe bicycling and vital public spaces — both for their own sakes and because they enable a city with fewer cars. While McKibben talks airily about stopping new fossil fuel infrastructure, we confront that infrastructure’s present manifestation daily in our city’s hellscape of cars and trucks.

Livable-streets advocates are counting down the 22 months left in de Blasio’s second and final term. We’re weary of his inane climate pronouncements and his cluelessness about what being a climate mayor really means. We yearn to be free of the spectacle of a mayor pontificating about Greta Thunberg while refusing to use mass transit.

But mostly we long for, and are resolved to elect, a mayor who at long last understands that breaking car culture lies at the heart of urban climate action.