On the same day that real crude oil prices broke a 28-year record, the Wall Street Journal heralded a long-awaited drop in U.S. gasoline consumption.

The Journal’s lead story today, Americans Start to Curb Their Thirst for Gasoline, was a powerful rebuttal of the notion that gasoline use is inelastic, and a vote of confidence in carbon tax advocates who have insisted that rising fuel prices will dampen energy demand.

Here are excerpts from the Wall Street Journal story, spiced with our commentary.

Here are excerpts from the Wall Street Journal story, spiced with our commentary.

As crude-oil prices climb to historic highs, steep gasoline prices and the weak economy are beginning to curb Americans’ gas-guzzling ways.

In the past six weeks, the nation’s gasoline consumption has fallen by an average 1.1% from year-earlier levels, according to weekly government data.

That’s the most sustained drop in demand in at least 16 years, except for the declines that followed Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which temporarily knocked out a big chunk of the U.S. gasoline supply system.

This time, however, there is evidence that Americans are changing their driving habits and lifestyles in ways that could lead to a long-term slowdown in their gasoline consumption.

Economists and policy makers have puzzled for years over what it would take to curb Americans’ ravenous appetite for fossil fuels. Now they appear to be getting an answer: sustained pain.

Of course, unlike the pain of "market-driven" high prices, the pain of socially mandated carbon pricing would be offset by rebating the revenue or tax-shifting.

Over the past five years, the climb in gasoline prices, driven largely by the run-up in crude oil, hardly seemed to dent the nation’s growing thirst for the fuel.

Conventional thinking held that consumption would begin to taper off when gasoline hit $3 a gallon.

But $3 came and went in September 2005, and gasoline demand didn’t flinch. Consumers complained about the cost of filling their tanks, pinched pennies by shopping at Wal-Mart, and kept driving.

Economists who study the effects of gasoline prices on demand say consumers tend to look at short-term price spikes as an anomaly, and don’t do much to change their habits. They might spend less elsewhere to compensate, or take short-term

conservation measures they can easily reverse, such as driving slower or taking public transportation, but the impact is minimal.Regular gasoline prices jumped to $2.34 a gallon at the end of 2006, up 62% from 2003, according to the EIA. Yet demand continued to grow at an average 1.1% a year. Consumers were better able to absorb the increase because it was spread over

four years, and the economy was doing fairly well.

Then again, annual demand growth of just 1% while the economy was expanding at 3% was strong evidence of at least some short-run price-elasticity.

Today, a weakening economy is intensifying the effects of high gasoline prices… The combination of forces is prompting Americans to cut back on driving, sometimes taking public transportation instead. It’s also setting the stage for what may be a long-term slowdown in gasoline demand by forcing Americans to become more fuel-efficient faster.

"If you think about the fact that U.S. motorists are responsible for one out of nine barrels of oil consumed in the world…and that consumption is no longer growing the way it used to, that’s a major structural change in the market," says Adam Robinson, analyst with Lehman Brothers.

The longer gasoline prices remain high, the greater the potential consumer response. A 10% rise in gasoline prices reduces consumption by just 0.6% in the short term, but it can cut demand by about 4% if sustained over 15 or so years, according to studies compiled by the Congressional Budget Office.

The implied 0.4 long-run price-elasticity noted above is precisely the level we (CTC) assume in our 4-sector carbon tax impact model, which may be downloaded here.

As consumers make major spending decisions, such as where to live and what kind of vehicle to drive, they are beginning to factor in the cost of fuel. Some are choosing smaller cars or hybrids, or are moving closer to their jobs to cut down on driving. Those changes effectively lock in lower gasoline consumption rates for the future, regardless of the state of the economy or the level of

gasoline prices.Anne Heedt, of Clovis, Calif., has been moving toward a more fuel-efficient lifestyle for the past few years. She owns a Toyota Prius hybrid but takes her bike on errands when weather permits.

"We’re not always going to have the same accessibility to gasoline that we’ve had in past decades, so we do have to start thinking about what we’re going to do over the next 50 years," said the 31-year-old Ms. Heedt, who used to work at a

medical office but is between jobs.

Way to go, Anne. You should be CTC’s poster child!

The housing boom encouraged the development of far-flung suburbs, contributing to longer commutes. Now developers are building more walkable neighborhoods close to city centers and public transit, and Americans are beginning to migrate back toward their workplaces, city planners and other experts say.

David Hopper, who lives in the rural community of Markleville, Ind., is preparing to move to a new house in Plainfield, cutting his commute to Indianapolis to 15 miles from 47 miles. Mr. Hopper decided to move closer to the city last summer, when gas prices hit

$3.40 a gallon in his area.

Together, Anne’s and David’s examples suggest the broad range of ways in which individuals respond to carbon-pricing signals. It’s heartening to see this reporting in a major paper like the Journal.

Pinched consumers also are speeding up their shift to more fuel-efficient cars. Sales of large cars dropped by 2.6% in 2006 and by 10.5% in 2007. In January, they plummeted 26.5% from a year earlier, according to Autodata Corp.

Car dealers are selling fewer minivans and large sport-utility vehicles. In fact, only small cars and smaller, more fuel-efficient SUVs, are showing a rise in sales. Small-car sales in January were up 6.5% from a year earlier, while sales of crossover vehicle grew 15.1%, Autodata Corp. says.

These trends evidently deepened in February. The New York Times reports that sales of SUV’s and pickups in the U.S. fell 14% last month, vs. a 5% drop in car sales.

Music to our ears. Meanwhile, the The Times is reporting that crude oil prices finally surpassed the historical inflation-adjusted peak from April 1980. How sad for Americans that the record-high price includes fabulous "rents" for oil owners and extractors. How much better instead to tax carbon fuels and re-allocate the revenues to American families.

Photo: bicyclesonly / Flickr

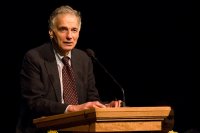

The article ends months of speculation that Bloomberg, a self-made billionaire who has emphasized a managerial, non-partisan approach to governing, would enter the race as an independent.

The article ends months of speculation that Bloomberg, a self-made billionaire who has emphasized a managerial, non-partisan approach to governing, would enter the race as an independent. While Nader has been roundly criticized and even ridiculed as a spoiler and perennial candidate (Nader was the Green Party candidate for president in 1996 and 2000, and he ran as an independent in 2004), his campaign platform includes unambiguous support for a carbon tax. “Adopt a carbon pollution tax” is Issue #6 on Nader’s campaign issues page,

While Nader has been roundly criticized and even ridiculed as a spoiler and perennial candidate (Nader was the Green Party candidate for president in 1996 and 2000, and he ran as an independent in 2004), his campaign platform includes unambiguous support for a carbon tax. “Adopt a carbon pollution tax” is Issue #6 on Nader’s campaign issues page,

According to the same story, climate specialist Ian Bruce of the David Suzuki Foundation stated that "The Government has used the most powerful tool, a carbon tax, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions." As Bruce pointed out, "Green choices will become cheaper."

According to the same story, climate specialist Ian Bruce of the David Suzuki Foundation stated that "The Government has used the most powerful tool, a carbon tax, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions." As Bruce pointed out, "Green choices will become cheaper."